The faked passports which saved countless lives

23.08.2023

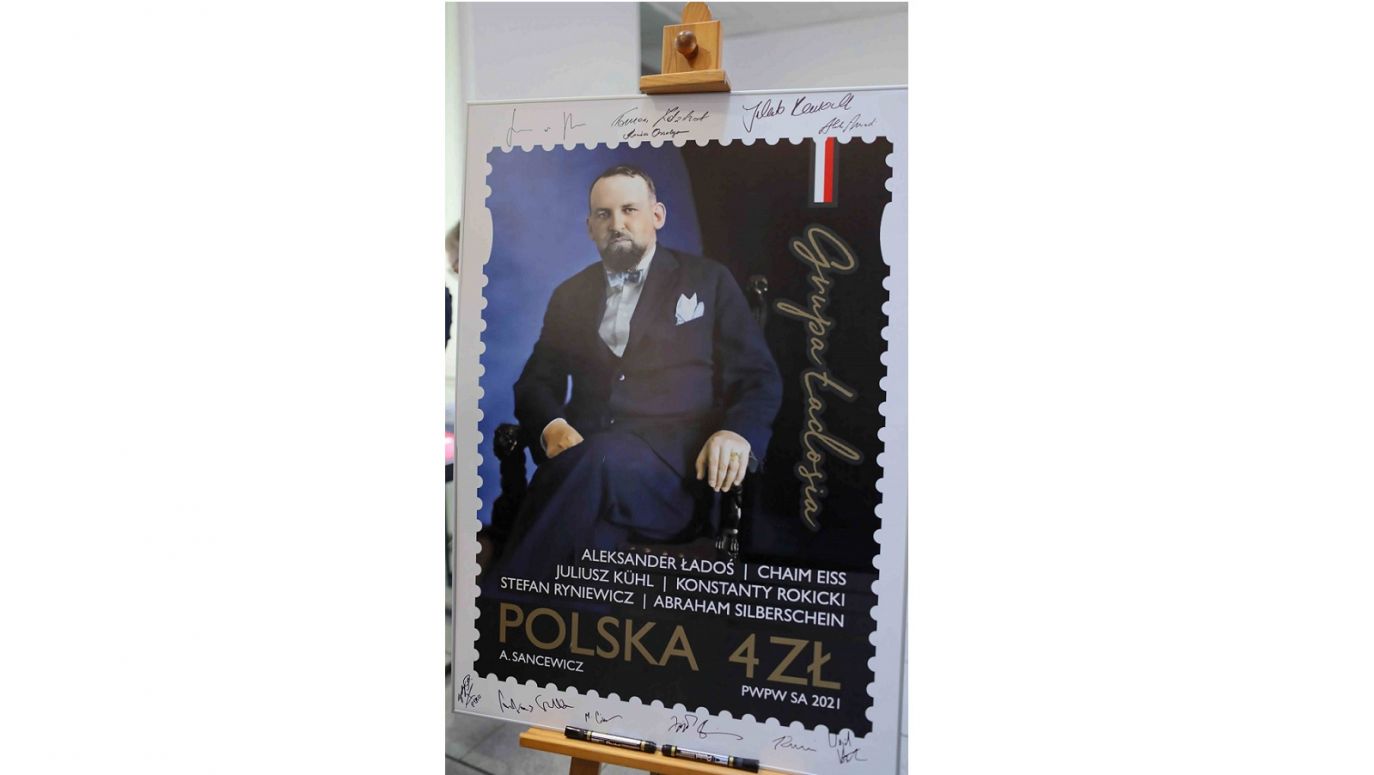

For a professional diplomat, Aleksander Ładoś had a rather casual attitude toward official documents. He was willing to bend formal rules in the name of a higher necessity - says Roger Moorhouse, a British historian and author of the book The Forgers, describing the so-called Łados Group. that has just been published in the United Kingdom.

TVP WEEKLY: The history you have been dealing with confirms that history itself has many undiscovered sides. How is it possible that the deeds of Ładoś were unknown for so many years? Not even more for the world, but also for Polish historians. Apparently, a trace of them was found quite by accident. Why did not anyone know about it after the war?

ROGER MOORHOUSE : A few people did know, but the story of the rescue efforts was then forgotten. Later when the history of the Holocaust began to be studied and written, they had already slipped from public consciousness and then were not brought into the Holocaust narrative. There are two pathways by which narratives are usually incorporated into the historiography of the Holocaust – official documents and personal testimony – and in this case both pathways failed. The official route failed because the communist takeover of Poland after the war consigned Ładoś and his fellows to obscurity and the relevant files disappeared into the archives of the Polish government in exile in London. The other pathway – that of personal testimony – failed because so few of those that received Ładoś passports, and survived, actually knew where that passport had come from. So, the name of Ładoś and the others were effectively consigned to the archives and forgotten, only to be rediscovered, by chance, in 2017.

Your book is a story about salvation, but I expect some heartbreaking pieces.

There are so many heartbreaking stories in the book that it is honestly hard to pick out a single one. The stories surrounding the Hotel Polski episode are incredible, not least as so many of those who were there were profoundly suspicious that it was a trap, and yet they were so exhausted by their travails that many of them went along with it anyway – and many of them went to their deaths. It is often said in this context that it was the hope that would kill you. And you can see that in these stories. Because of the passports and the hope that they might be recognized as foreign Jews and exchanged, those that held Ładoś papers had hope – more hope than most – and the way in which those hopes were so cruelly dashed make so many of the stories especially heart-rending.

Importantly, I think, there are also moments of light and laughter and empathy in the book – characters like Louis Tas, who recorded life in Bergen-Belsen with the wry eye of a snarky teenager, or the heart-warming story of Professor Ajzenmann.

In German-occupied Europe, the Latin American document it was a ticket to life. The poet of the Warsaw ghetto, Władysław Szlengel, wrote: 'I would like to have a Uruguayan passport / Oh, what a beautiful country it is / How beautiful it must be to be a subject / Of the country called Uruguay...

What was the risk for the members of the group, the Polish diplomats Stefan Ryniewicz, Consul Konstanty Rokicki and Aleksander Ładoś himself?

There wasn’t much immediate peril, it must be said. They were in Switzerland, so were rather safe from the perils of German-occupied Europe, and they were diplomats and so should have enjoyed diplomatic immunity in the event of any legal challenge to their actions. Still, German military intelligence did try to infiltrate the circle around the group, and – given the comparative hostility of the Swiss to what they were doing – they still would have had some considerable concern for their own safety. Bear in mind that German pressure on the Swiss police was considerable at this time, and Switzerland – exposed as it was – was often obliged to accede to German demands.

Do we have a true righteous man in the righteous among the peoples of the world? What do you find in A. Ładoś personality, what was his motivation?

His motivation was humanitarian, quite simply. In terms of his background, he was from Lwow, and was a member of the Peasant Party, and had been cast out of the diplomatic service following Pilsudski’s coup in 1926, thereafter he worked as a journalist. When he arrived with the government in exile in France in 1939, he was considered of value because of his diplomatic experience, and so was offered an ambassadorial position.

Significantly, he had benefited from a forged passport as a young man, when he escaped from Tyrol into Switzerland, so we can surmise that – perhaps unusually for an ambassador – he was not especially concerned about the sanctity of official documents. He was willing to bend the rules in the name of a higher morality.

A few days ago, Daniel Finkelstein, a member of the House of Lords and a columnist for The Times, wrote an enthusiastic review of your book, recalling that one of the people saved from the Holocaust thanks to the forged passports of the Ładoś-group was his mother. In his column, Finkelstein declared that Aleksander Ładoś deserved the title "Righteous Among the Nations." This title hasn't yet been awarded. What problem does the Yad Vashem Institute have with Aleksander Ładoś?

I don’t think it is that Yad Vashem has a problem with Ładoś, I think it is rather that they are to some extent running to catch up with a developing story. The Ładoś story only really came to light in the last decade or so, and Konstanty Rokicki – whose handwriting is on the Ładoś passports – was recognized as Righteous in 2019, so I think it is just a matter of time until Ładoś is afforded the same honour.

Part of the problem, of course, is that one of the primary criteria for Righteous status is that it is based on the evidence of survivors. And, given that the vast majority of those the survived the Holocaust with a Ładoś passport did so with very little knowledge of where that passport had come from and who prepared it, this presents a problem. Still, hopefully, this book and the growing recognition of the wartime actions of the Ładoś Group can help the process along.

Did you know that the question of whether the Poles helped the Jews is very controversial among the Poles themselves? Even within the family or among friends, one can argue whether we were generous or despicable during the war.

Of course, I understand that it is hugely emotive and controversial as it goes to the heart of both the Polish and the Jewish sense of themselves. In truth, Polish reactions to the plight of the Jews in the Holocaust spanned the spectrum. There were heroes and villains and everything in between: from Irena Sendler and Zofia Kossak to individual szmalcownicy who sought to profit from Jewish suffering. And the vast majority, of course, were merely trying to survive themselves, under the crushing brutality of the German occupation regime. It takes a tremendous amount of bravery to risk the lives of yourself and your family for someone else.

And what do the Poles have to be thankful for?

see more

How do you judge the attitude of the Poles towards the Holocaust, not as a Polonophile, but as a completely objective historian researching this topic?

As I said before, I think the Polish response to the Holocaust spans the spectrum, from the admirable to the awful. And in that, I think it is a very human response, similar to what was seen elsewhere in occupied Europe, the only exception being the fact that such a large proportion of the victims of the Holocaust were Polish Jews, and – uniquely – the death penalty was imposed for Poles helping Jews, so the stakes were that much higher.

Modern Poland has much to be proud of in its reaction to the Holocaust. The fact that the largest number of Righteous among the Nations are Poles shows that it was possible to do the right thing, even at the risk of one’s own life.

But there were also reactions that should provoke a sense of shame: the many betrayals and rejections of Jews – as evidenced by numerous Jewish memoirs from the time – as well as those who sought to exploit Jewish suffering for their own gain. Of course, to a large extent, those negative reactions were themselves the result of circumstances. Totalitarian systems force those living under them to make choices that they would never normally have to face.

The key difficulty here is for modern Poland to reconcile that spectrum of reactions – the positive and the negative, and everything in between – into a coherent wartime narrative and a “usable past”, which recognizes that history is not always black and white, it is often a complex palette of shades of grey.

Do not you think that 80 years after the Holocaust there is still no reliable evaluation of this tragedy? I.e. not about the perpetrators, but about the attitude of the Allies to the extermination. You know, it was very difficult to read anything about the Hamilton Conference (which started on April 19, 1943) in English sources or websites.

There are many aspects of this story that have not really been written about before – look at the stories around the Exchange Jews, or the Hotel Polski. That, sadly, is the nature of the beast. A lot of popular history is essentially regurgitative – it repeats the same stories that are well known, just with a little twist – but it doesn’t want to explore genuinely new material or new stories. That is a failing of the business, not only on the part of the historians and authors that write the books, but also on the publishers who often prefer the old “tried and tested” narratives. I always like to examine something new, which is why this story appealed to me.

How do you judge the attitude of the Poles towards the Holocaust, not as a Polonophile, but as a completely objective historian researching this topic?

As I said before, I think the Polish response to the Holocaust spans the spectrum, from the admirable to the awful. And in that, I think it is a very human response, similar to what was seen elsewhere in occupied Europe, the only exception being the fact that such a large proportion of the victims of the Holocaust were Polish Jews, and – uniquely – the death penalty was imposed for Poles helping Jews, so the stakes were that much higher.

Modern Poland has much to be proud of in its reaction to the Holocaust. The fact that the largest number of Righteous among the Nations are Poles shows that it was possible to do the right thing, even at the risk of one’s own life.

But there were also reactions that should provoke a sense of shame: the many betrayals and rejections of Jews – as evidenced by numerous Jewish memoirs from the time – as well as those who sought to exploit Jewish suffering for their own gain. Of course, to a large extent, those negative reactions were themselves the result of circumstances. Totalitarian systems force those living under them to make choices that they would never normally have to face.

The key difficulty here is for modern Poland to reconcile that spectrum of reactions – the positive and the negative, and everything in between – into a coherent wartime narrative and a “usable past”, which recognizes that history is not always black and white, it is often a complex palette of shades of grey.

Do not you think that 80 years after the Holocaust there is still no reliable evaluation of this tragedy? I.e. not about the perpetrators, but about the attitude of the Allies to the extermination. You know, it was very difficult to read anything about the Hamilton Conference (which started on April 19, 1943) in English sources or websites.

There are many aspects of this story that have not really been written about before – look at the stories around the Exchange Jews, or the Hotel Polski. That, sadly, is the nature of the beast. A lot of popular history is essentially regurgitative – it repeats the same stories that are well known, just with a little twist – but it doesn’t want to explore genuinely new material or new stories. That is a failing of the business, not only on the part of the historians and authors that write the books, but also on the publishers who often prefer the old “tried and tested” narratives. I always like to examine something new, which is why this story appealed to me.

How do you judge the attitude of the Poles towards the Holocaust, not as a Polonophile, but as a completely objective historian researching this topic?

As I said before, I think the Polish response to the Holocaust spans the spectrum, from the admirable to the awful. And in that, I think it is a very human response, similar to what was seen elsewhere in occupied Europe, the only exception being the fact that such a large proportion of the victims of the Holocaust were Polish Jews, and – uniquely – the death penalty was imposed for Poles helping Jews, so the stakes were that much higher.

Modern Poland has much to be proud of in its reaction to the Holocaust. The fact that the largest number of Righteous among the Nations are Poles shows that it was possible to do the right thing, even at the risk of one’s own life.

But there were also reactions that should provoke a sense of shame: the many betrayals and rejections of Jews – as evidenced by numerous Jewish memoirs from the time – as well as those who sought to exploit Jewish suffering for their own gain. Of course, to a large extent, those negative reactions were themselves the result of circumstances. Totalitarian systems force those living under them to make choices that they would never normally have to face.

The key difficulty here is for modern Poland to reconcile that spectrum of reactions – the positive and the negative, and everything in between – into a coherent wartime narrative and a “usable past”, which recognizes that history is not always black and white, it is often a complex palette of shades of grey.

Do not you think that 80 years after the Holocaust there is still no reliable evaluation of this tragedy? I.e. not about the perpetrators, but about the attitude of the Allies to the extermination. You know, it was very difficult to read anything about the Hamilton Conference (which started on April 19, 1943) in English sources or websites.

There are many aspects of this story that have not really been written about before – look at the stories around the Exchange Jews, or the Hotel Polski. That, sadly, is the nature of the beast. A lot of popular history is essentially regurgitative – it repeats the same stories that are well known, just with a little twist – but it doesn’t want to explore genuinely new material or new stories. That is a failing of the business, not only on the part of the historians and authors that write the books, but also on the publishers who often prefer the old “tried and tested” narratives. I always like to examine something new, which is why this story appealed to me.

How do you judge the attitude of the Poles towards the Holocaust, not as a Polonophile, but as a completely objective historian researching this topic?

As I said before, I think the Polish response to the Holocaust spans the spectrum, from the admirable to the awful. And in that, I think it is a very human response, similar to what was seen elsewhere in occupied Europe, the only exception being the fact that such a large proportion of the victims of the Holocaust were Polish Jews, and – uniquely – the death penalty was imposed for Poles helping Jews, so the stakes were that much higher.

Modern Poland has much to be proud of in its reaction to the Holocaust. The fact that the largest number of Righteous among the Nations are Poles shows that it was possible to do the right thing, even at the risk of one’s own life.

But there were also reactions that should provoke a sense of shame: the many betrayals and rejections of Jews – as evidenced by numerous Jewish memoirs from the time – as well as those who sought to exploit Jewish suffering for their own gain. Of course, to a large extent, those negative reactions were themselves the result of circumstances. Totalitarian systems force those living under them to make choices that they would never normally have to face.

The key difficulty here is for modern Poland to reconcile that spectrum of reactions – the positive and the negative, and everything in between – into a coherent wartime narrative and a “usable past”, which recognizes that history is not always black and white, it is often a complex palette of shades of grey.

Do not you think that 80 years after the Holocaust there is still no reliable evaluation of this tragedy? I.e. not about the perpetrators, but about the attitude of the Allies to the extermination. You know, it was very difficult to read anything about the Hamilton Conference (which started on April 19, 1943) in English sources or websites.

There are many aspects of this story that have not really been written about before – look at the stories around the Exchange Jews, or the Hotel Polski. That, sadly, is the nature of the beast. A lot of popular history is essentially regurgitative – it repeats the same stories that are well known, just with a little twist – but it doesn’t want to explore genuinely new material or new stories. That is a failing of the business, not only on the part of the historians and authors that write the books, but also on the publishers who often prefer the old “tried and tested” narratives. I always like to examine something new, which is why this story appealed to me.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE