Young teachers, themselves after overseas scholarships and grants, need to encourage young people to take on challenges.

see more

How can this experience be put into practise? Schools are often poorly equipped...

Mine is richly equipped, albeit with very basic gadgets - the most expensive gadget I have cost $20 on Amazon. All the others are homemade 'toys', often inspired by what other teachers post on YouTube. The internet is a very valuable source of inspiration, and I watch a few channels all the time. For example, there are great channels - from a teacher from the US and from Novosibirsk, where they show different experiments that can be done with a simple 'MacGyver-style' method. I have plenty of such material so that the children (there are a maximum of 18 in the class) can carry out experiments independently in pairs. I also prepare videos of experiments that can easily be done in class.

It's time to slow down a bit at school. There is a trend for "slow fashion", "slow food", let there also be a fashion for "slow school". In such a school, the teacher would choose the subjects with which he or she can work best, and necessarily in such a way that they are adapted to the abilities of the individual pupils. And so much for primary school. Secondary school should not take on the role of universities. It should be a school that develops independent thinking and constant training of the grey matter. And if someone wants to become a specialist in a particular field, that's what universities are for. However, it is not good to come and be so qualified at the beginning that you can "let go" of the first semester, because then the awakening can be painful.

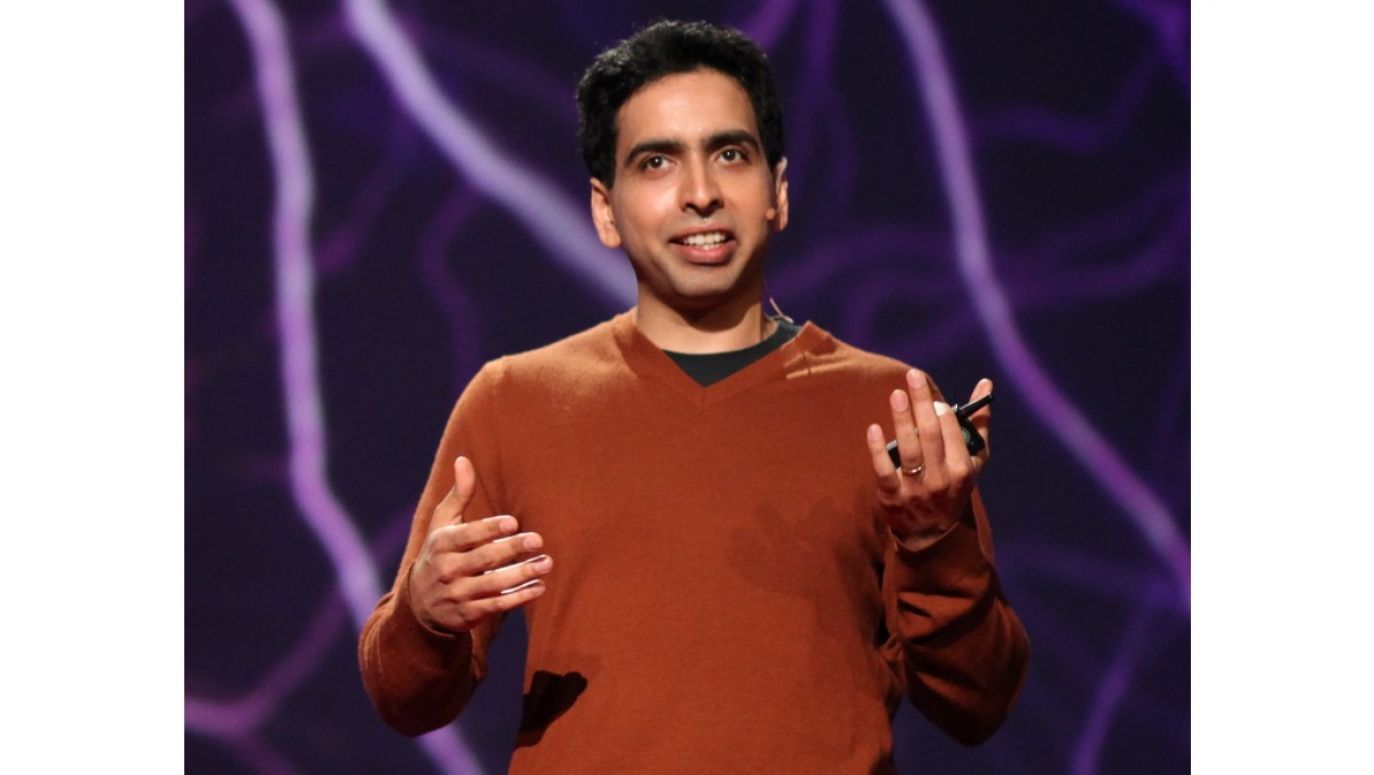

You use the rich resources of the internet. The question remains: How do you individualise this content? Because I think that's exactly what Sal Khan's actions were about - he also individualised these videos.

My students use the content available on the Internet, but I also create it for them myself. Because I know them. For the Khan Academy materials, we really choose specialists who can explain and reach the audience. However, when using pre-made materials, I have found that when a lesson with a video gives a different explanation than the one we discussed in class, the students have difficulty understanding the subject matter, even if the two explanations are completely equivalent. In the mysterious process of nesting abstract concepts in the brain, this phenomenon has proven to be one of the most important. Therefore, after each lesson, I record videos summarising the material "in our own language", which can be viewed on the school's YouTube channel. The children are expected to complete their notes each time, as processing and internalising knowledge is very important. I also try to revisit previously covered content in different new contexts.

What would the reform of our education consist of in this context? Does it have to be a revolution?

Digital resources bring a lot to education, but using them is more difficult than many people think. Sal Khan has triggered a revolution in education, but that has already happened. To build a meaningful framework on top of that to help children learn, a lot more effort needs to be put in than just presenting a film. I am a big sceptic of these proposed revolutions in Polish education, but I don't want to get into any more verbal arguments on social media about it. The interlocutors are probably too often people who know everything better, but unfortunately at least some of them have not been in the classroom for a long time.

Any changes in school should focus on exactly what was mentioned above - that the teacher must act in such a way that the student comes out of the lesson with something concrete. There is a lot of talk about relationships in school, and rightly so, although there are exceptions. Of course, it's better if there's a cool atmosphere in the classroom and we tend to smile at each other, and I never push them too hard. The problem remains how to get the children to develop in THIS SPECIFIC subject. Pedagogy doesn't care, because pedagogues don't graduate in maths or physics. Films can be a gateway to the garden of knowledge, but the child must have the key with them..

And here the very use of the language of numbers or symbols to describe something is a breakthrough (algebra is only introduced in Year 7), which instils fear in the children, an atavistic distance to the unknown. Dealing with this is the whole point of the job of a maths and science teacher, not whether I have managed to go through all kinds of tasks with them. In this respect, even the best teacher-student relationships are not particularly helpful. They are necessary, but not sufficient.

In other words, the methodology of how to successfully teach certain subjects remains mysterious.

We have some achievements here, but they have nothing to do with digital education.

– interview: Magdalena Kawalec-Segond

TVP WEEKLY. Editorial team and jornalists

–Translated by Cezary Korycki

Dr Lech Mankiewicz, Professor at the Polish Academy of Sciences. Physicist and astrophysicist, as well as populariser of natural sciences, for over 20 years associated with the Centre for Theoretical Physics of the Polish Academy of Sciences, which he headed in 2007-19. He is strongly involved in international educational initiatives as the Polish coordinator of the EU-HOU programme (Hands-On Universe, Europe) or as the person responsible for the Polish language version of the global educational portal Khan Academy. His contribution to the dissemination of astronomical knowledge (e.g. the possibility for students and teachers of Polish schools to conduct their own regular observations of the cosmos as part of the EU-HOU programme) was awarded the Zonn Medal by the Polish Astronomical Society in 2011. Thanks to a suggestion from students participating in the International Asteroid Search Campaigns, the main belt asteroid (279377) 2010 CH1 was named Lechmankiewicz.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE