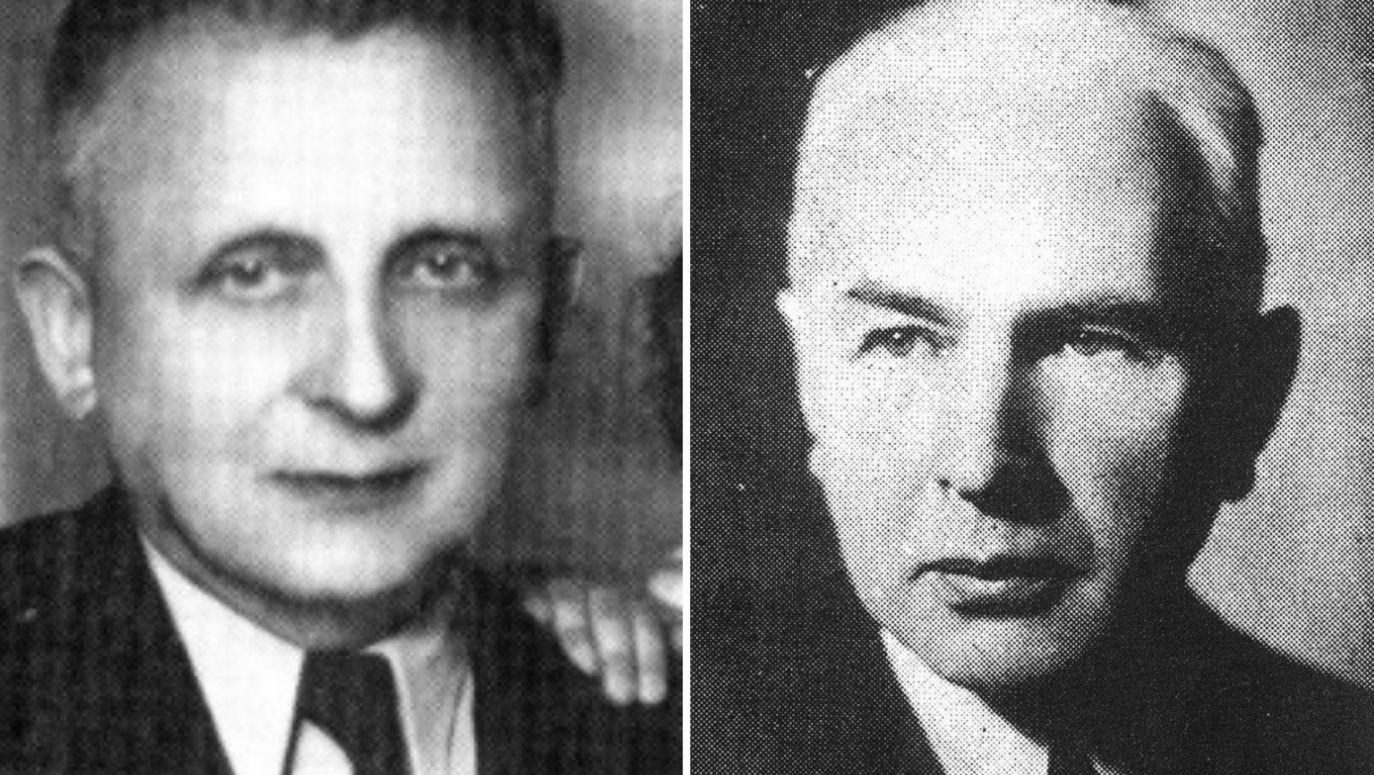

Although many writers have written about the rescue and hiding of the "Battle of Grunwald" painting from the Germans, the whole story of what actually happened 80 years ago remains unknown to this day. The role played by Stanisław Kalinowski and Roman Ślaski has never been described properly, whether in the media or in literature. "The propagandists of the [communist] organs of the PKWN are laughing in their graves having done such a great job concealing it, " says historian Dr. Gapski.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

If Rafael, Bernini or Bach were looking for work, which diocese would hire them?

see more

Art is a powerful weapon, especially when it comes to winning over fussy intellectual elites.

see more

The trick invented by the Chinese in the 12th century, was patented in Europe in 1787.

see more

The artist was too defiantly bourgeois to attract the attention of cultural decision-makers in Poland’s People's Republic.

see more