Virtual Reality of the Barouche Era. The Forgotten Art of Panoramic Paintings

08.06.2022

They allowed the spectators to admire the struggles of the Battle of Trafalgar, the crowded streets of London and the sand dunes of Scheveningen, Jerusalem on the day of the Crucifixion and the arrival of the Hungarians in the Pannonian Plain. The battles of Waterloo, Borodino and, of course, Racławice, as well. The last one for 128 years, from the unveiling of Jan Styka and Wojciech Kossak’s work in Lviv (Lwów) on June 5, 1894.

Be it clump of trees, a chimney, a tower, or a crowd of people, there is always something to obstruct the view. And if you take a busy city, the mountains or the forest, something is simply bound to block the sight. A solution as old as the worlds itself, is to climb somewhere higher: daddy’s shoulders, a pole, tree branches, all these may serve the curious during battles and competitions.

And once you climb really high, you might just take a good look around. You may turn your head to the left, to the right, - and the whole world suddenly seems raised on its edges as if it were a big bowl. And how about painting it like that?

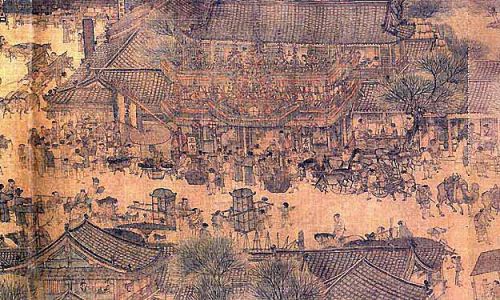

Paintings featuring the horizon have long been known to world civilizations. The Chinese are the leaders here (as usual in such cases): Along the River During the Qingming Festival by Zhang Zeduan was created at the end of the Song Dynasty, that is in the 12th century. The five-meter long scroll capturing the crowded Kaifeng with its inhabitants convivially celebrating a festival somewhat resembling our Forefathers Eve, or the All Souls’ Day, is full of farm animals, litters, carriages, boats and, most of all, silhouettes of people, 814 to be exact (well, it’s China!).

Long view of the city

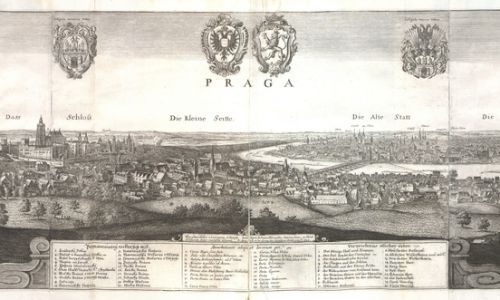

However, it weren’t only the Chinese. Starting from the 17th century, European engravers, more and more often painted the so-called perspectives or “long views” of cities, featuring the entire town “from end to end” on one disproportionately long canvas. In this way, rather than replicating what can be seen with a single glance, they, as it were, “stitched” together successive views in one picture. Vaclav Hollar, a citizen of Prague was the most famous artist creating such works. The Thirty Years’ War cast Hollar first to Cologne, and then to London - where, already known as Wenzeslaus, he gained his followers and made a fortune.

A real novelty was the idea put forward by the man of the Age of Reason, an Irishman Robert Baker. It was not just about “sticking” together subsequent views that can be seen from the top of a tower or a hill. The observer was supposed to experience being on a top of a tower or a hill and just by turning the head be able to see the whole horizon! To see everything thanks to the power of the human mind: “everything” or in classical Greek pan and “view” or horama . Had Baker been a more diligent reader of Horace rather than Homer in his public-school days, he would have probably come up with “omniapictura”. However, he would not have come up with anything for that matter, had it not been for another invention of the Enlightenment: the first critics of panoramic paintings noticed that the view they depictured was remarkably reminiscent of a visual experience during a balloon flight.

In the past, people liked to romanticize the moment of discovery or invention: Archimedes is said to have discovered the law of buoyancy in his bath, Newton allegedly got hit by a falling apple... Did Baker really get an inspiration while walking on Calton Hill near Edinburgh? That we don’t know, but he surely patented his idea in 1787, and a year later the Panorama of Edinburgh from Calton Hill saw the light of day.

The light of the day - but filtered through the panes of the glass ceiling. It is one of the paradoxes of panoramic paintings that they produce an image that is surprisingly close to the natural one, the effect being achieved by an exceptional accumulation of means enhancing the illusion and modifying “natural conditions”. As one of epistemologists fascinated with panoramic paintings once put it: the spectator rather than admiring a painting in a gilded frame, is drawn into that frame, and thus becomes part of the painting!

Indeed. The first Baker’s panorama to be preserved to our times, that is, London from the Roof of Albion Mills (1801) and the way it was presented, in fact defined the canon of this art. Since then, the canvases have grown in size and the level of detail (the London from the Roof... measured about 250 square meters, while panoramas of the end of the 19th century usually exceeded a thousand square meters, and the Chinese still did not say their last word!).

The shape of the scaffolding on which the canvases were stretched slightly changed: initially it was a simple cylinder, as if copied straight from an elementary school geometry textbook. However, in the middle of the century, following the advice of opticians, it was decided that this cylinder would be slightly concave in the middle (mathematicians call this shape a circular hyperboloid but we don’t need to get into more detail here.)

View from inside the cylinder

The essence, however, remains the same: the spectator of a panoramic painting is standing at its central point, able to turn or walk a few steps to see the entire horizon around him, full 360 degrees. Usually, the viewer is located half-way the height of the canvas and a dozen or, sometimes several dozen meters away from it so that he cannot tell whether or not it is a painting. Individual parts or planes of the panoramic landscape (a 150-meter-long canvas could not be painted as one piece, as no one would be able to lift it later and stretch it over the scaffolding) were sewn together and the seams were additionally painted over. The room was usually entered through an underground corridor plunged in the darkness - in order to “suppress the senses”. And once you have entered the main hall…

Streams of light - from above, sometimes also from the side (some dioramas were painted on a thin, translucent canvas to enhance the impression of plasticity and three-dimensionality). Blows of fresh air - from invisible vents. The upper edge of the panorama is usually invisible, as it disappears in the twilight. Similarly, the lower one - is located under the surface of the room. To make the illusion more complete, the so-called staffage: numerous items that created the illusion of three dimensions, were placed in front of the bottom part of the canvas.

There was everything there! To add splendour to the panorama of the Scheveningen dunes by Hendrik Mesdag, tons of coastal sand, trunks and nets washed up by the sea were placed in front of the painting. The view of Jerusalem would not have been complete without the columns and rock debris in the foreground, Kossak and Styka would bring old cannons and guns from wherever they could to reflect more faithfully the battlefield of Racławice.

And - as it happens with inventions - it took off! Under English law, Baker lost his exclusive rights in the second decade of the nineteenth century and soon panoramas began to be counted in dozens, maybe even hundreds? The Swiss painted the Alps, the French – Napoleon’s battles, the Russians - also Napoleon’s battles (well, maybe just one - Borodino) and the Crimean wars, the Americans - Niagara or Mississippi, and all of them - views of Rome, Naples, Venice and Athens.

Coppola's work carries an important warning: The "success" of a family can be the road to its disintegration.

see more

Number of orders increased, fortunes were made, and the critics turned up their noses – just as usual when it comes to the media. Interestingly, panoramas were most often criticized from the aristocratic (or, to use a more modern term, “oligarchic”) standpoint. And thus, other sceptics, starting with William Wordsworth, one of the greatest romantic poets, began to point to the “vulgarity” of the panorama: for only three shillings (quite a lot, actually, at that time), each visitor can reach the clouds, get immersed in the landscape and touch a lofty past having received no prior education in art! It is more of a market gimmick than great art!

Just “Wow!”

We have to admit though that Wordsworth might have had a point here. Indeed, paintings (both classical and romantic) required some knowledge and a degree of sophistication. Spectators had to “read” them, tracing both allusions and hidden religious or mythological meaning. Moreover, the visual language - fog, light, shadows, colours - commonly conveyed additional meaning. The panorama on the other hand did not carry any meaning except the one contained in thousands of details and the reaction most expected by the creators was a simple “Wow!”.

Inventors of a lateral evolutionary path, i.e., the so-called moving panoramas introduced in the mid-nineteenth century could especially count on this “wow” effect. They really no longer cared for the artistry, but only for providing as many impressions and travel experiences as possible. Even a few hundred meters long canvas (of course, sewn together from many pieces) was wound on two gigantic rollers and gradually unfolded in front of the delighted audience, just like a film or audio tape, only much slower. Therefore, the spectators could see the views of the Amazon jungle, the banks of the Nile or hunting whales. Just moving pictures every inch - only in a very long shot.

The Trans-Siberian Railway Panorama, designed by a painter, Paweł Piasecki, for the World Exhibition in Paris in 1900, was an unparalleled achievement in this field. The 942 meters long canvas showed the views that could be seen outside the window of the carriage travelling from Samara to Vladivostok. It was “displayed” (i.e.: unfolded) outside the windows of a real Trans-Siberian Railway carriage, specially delivered to France for this purpose. Visitors to the World Exhibition sat in their armchairs - and looked, and looked...

The carriage was placed on special springs, which produced the sensation of rocking typical of railway travel. The clack of switches was recreated from the phonograph. The staffage, i.e., three-dimensional objects, were in abundance. They were placed below the carriage windows on three separate conveyors: the closest to the viewers, filled with sand, rocks and trunks, was moving with a speed of 300 meters per minute. The middle one (it was actually a separate micro-panorama with painted grass and bushes) was speeding at the rate of 120 meters per minute, the next screen showing trees and deserts was moving slower - 40 meters per minute.

The main panoramic painting, with views of the cities and mountain peaks, was moving with a speed of 5 meters per minute (as it is easy to calculate, the full Trans-Siberian session lasted over three hours). Isn’t it a fantastic virtual reality from the belle epoque?

National emotions

However, that was in fact entertainment for the common. The middle class wanted to admire static panoramas - and feel patriotic and sublime at the same time. Consequently, in the second half of the 19th century, panoramas that enjoyed a renaissance of popularity featured mainly the great “founding battles” of individual nations, sometimes also the landscapes recognized as landmarks of given countries. The Arrival of the Hungarians (A magyarok bejövetele) by Árpád Feszty has already been mentioned above. The Americans treated themselves (of course) to the Battle of Gettysburg, the Russians (of course) - Borodino and Sevastopol. And the Poles? Well, everybody knows.

Everybody, but not everything. It is known that the panorama was commissioned in 1893 by the Lviv City Council (at that time, it must be membered, the capital of Galicia!) to celebrate both the centenary of the Insurrection and the General National Exhibition planned for 1894. “When I came up with the idea of executing this work, it was not just to celebrate the triumph of the Polish army, because Poland had had greater victories in its history, but I also intended to show a moment when all classes were united to defend the Homeland a hundred years ago. I wanted to honour the name of the grandest hero of freedom, Kościuszko” - declared the artist during the ceremony of unveiling the Panorama 128 years ago.

It is known that both leading artists, Jan Styka and Wojciech Kossak, first carried out detailed field studies in the April mud near Racławice (they reached as far as the hill in Dziemięrzyce – The Panorama ... recreates the view from the rape field located there), and then – they searched through the Viennese military archives, where sketches of the battlefield had been preserved... Battlefield tactics were consulted by Prof. Tadeusz Korzon, colours and weapons by prof. Konstanty Górski. The panorama was painted by almost a platoon, or at least a squad - apart from Styka (scythe-bearers) and Kossak (most of the horses and Russian infantry), especially noteworthy were: Ludwik Boller (the sky), Tadeusz Popiel (trees, cottages), Teodor Axentowicz (the 2nd Crown Infantry Regiment) and Włodzimierz Tetmajer (commoners).

But not everyone remembers that the success of the Racławice Panorama almost led to the birth of the “Polish school panorama painting”!

Jan Styka, a truly entrepreneurial artist, benefited the most. First, he accepted a gigantic order from the Hungarians on the so-called Transylvanian Panorama - an image of the victory of the insurgents from the times of the Spring of Nations near Sibiu. In addition – they were led by General Bem, therefore it was also a monument to Polish-Hungarian friendship ...

Business with Hungary

The work was gigantic - 120 meters in circumference and 15 meters high, i.e., of the same height as the Racławice Panorama. The unveiling ceremonial took place in Budapest (on the anniversary of the Spring of Nations in 1898), then - a tour of the lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen, well, even across the Congress Kingdom of Poland. Ultimately, however, despite the friendship, it turned out that the principals did not pay for the work. Outraged, Styka did what other authors of panoramas happened to more often than once: he cut the work measuring 1,800 square meters 2 into pieces, deciding to sell retail instead of wholesale.

Naturally, not all of it. He cut the 60 most impressive pieces (bayonet charge, cannon fire, officers smoking pipes) out of the 1,800 meters, signing them with his own name. The rest was repainted, and the less refined pieces (clouds over Transylvania, mountain slopes, forests) were sold, as the rumour has it, simply for tarpaulins. And that is why, although the Museum in Tarnów has been trying for years to recreate the whole of the masterpiece, it has only managed to collect just 38 pieces so far.

Styka would have painted even more - with another panorama he wanted to add splendour to the Krakow Barbican, i.e., the “Roundel”), which was mercilessly commented by Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński in his epigram (“Once Mr. Styka saw a common mongrel / Raising his hind leg to dirty the roundel. / And then our Master had a sudden insight / how about doing this messing from inside?). Nevertheless, the biggest Polish painting is the Panorama of the Tatra Mountains.

The artist was too defiantly bourgeois to attract the attention of cultural decision-makers in Poland’s People's Republic.

see more

Undoubtedly the biggest one: 115 m in circumference by 16 m high, which is 1840 square metres in total 2 . The work was, exceptionally, commissioned not to Styka, but to the tandem of Włodzimierz Tetmajer and Wincenty Wodzinowski. Other contributing painters included the earlier mentioned Boller (who paid for it with his life, having fallen from the scaffolding) and Axentowicz, but also by others - the crème de la crème of the Krakow Academy. The site (Miedziane Peak) was chosen by the greatest Polish expert of the Tatra Mountains of the late 19th century, Walery Eliasz-Radzikowski, a special brochure was written by another tatromaniac, Kazimierz Przerwa-Tetmajer, gentlemen artists, unused to climbing, scrambled up from the shelter in Morskie Oko to Miedziany Peak for two months to sketch the peaks and ravines, the crags and ridges of the spruce covered, dark stone runs, where “peacock-eyed ponds are dozing”. In Warsaw, at Dynasy a special building was erected for the Panorama of the Tatra Mountains party.

And? A total flop. The undertaking, which was supposed to bring its founders a fortune, turned out to be a dud investment: whether it was because the appearance of the cinematograph, or because simply too much money was put into depicting chamois ... All in all, just after less than three years the building was closed, and the panorama was cut into pieces and auctioned. The unforgiving Styka bought out more than half of the canvas (60 x 16 meters) to paint another panorama on the back of it, for which the Krakow ensemble had a grudge against him forever. Out of the whole undertaking, only two cardboard sketches of Stanisław Janowski were left together with the allegedly least successful intervention of the tsarist censorship, traced by Andrzej Dobosz. In one of his many moralizing poems, Stanisław Jachowicz (the one known for his “Mr. Kitten was ill ...”), who worked in Krakow, wrote the following words that might have been repeated by any good boy at that time:

I was given two zlotys by mamma,

So, I could see the panorama.

The poem was inspired by the Racławice Panorama and was about generosity. The latter, however, the censor in the “Country upon the Vistula” obviously lacked. In order to prevent mentioning the name of the “national” money used in Galicia at that time – he made a one-of-a-kind currency exchange, converting the zlotys into kopecks and ordered publishing the following version:

I was given twenty kopecks by mamma,

So, I could see the panorama.

.

Painting of Honecker’s times

It seemed that colour photos and the cinema, with all its special effects, would put an end to panoramas. Nothing of the kind! Panorama painters were once again put to work in the countries of real socialism. The “Second Renaissance of the Panorama” began with a canvas (115 x 15) painted by 11 Soviet and 2 Bulgarian artists to celebrate the centenary of the Battle of Plevna, which marked the beginning of Bulgaria’s liberation from the Ottoman yoke. The masterpiece honouring the rule of Todor Żiwkow inspired in turn Erich Honecker: a painting by artist Werner Tübke (123 x 14) was painted in the GDR for 21 years (1976-1987). It depicted the 16th-century uprising of Thomas Müntzer, known in historiography as the “German Peasants' War”, and more broadly - the birth of the progressive Renaissance (the canvas includes, among others, Nicolaus Copernicus, who did not take part in the struggles of the Franconian crowd).