Who knows if the moving scene from the American movie "Cabaret", when the singer from Hitler Youth seduces the visitors of the German Bierhaus with the power of his song, was not inspired by Lempicka’s memories. In 1938, Tamara and her husband, the baron, visited one of the resorts in Austria. They saw with their own eyes how the march of the Hitler Youth unit performing Nazi songs, in a split second turned the recuperating people watching this parade, into a sinister crowd engulfed in a Nazi frenzy. As Lempicka recalled, this experience prompted her to persuade her husband to sell his property in Hungary.

With the money obtained, they left overseas in February of 1939. The instinct to escape from the Bolshevik rule did not disappoint Łempicka. The war did indeed break out, and she, with her Jewish roots, would probably have ended up in one of the death camps of the Third Reich.

In America, she chose Hollywood for the location of her portrait studio. She received orders, but she was no longer such a big star as in Paris. She changed the painting style, moving towards hyperrealism, but she was not as successful as before the war. She had to face the fact that her style went out of fashion.

She compensated for the growing dissatisfaction with the dimming fame with numerous travels. Ultimately she settled down in Mexico, where she died in 1980. She had her ashes scattered from the helicopter over the hills of a Popocatepetl volcano.

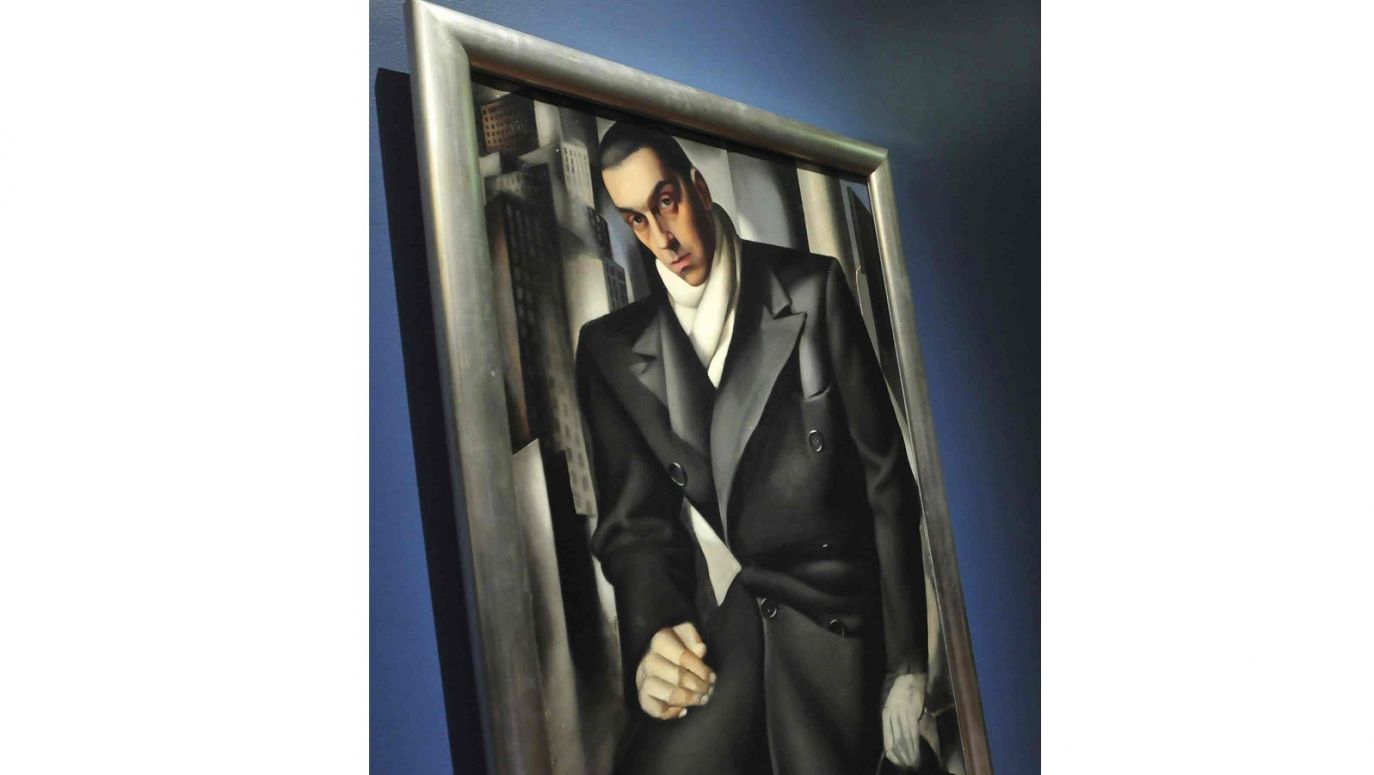

Already in 1973, she was rediscovered on the wave of retro fashion. In the 80s and 90s of the 20th century and at the beginning of this one, there are large monographic exhibitions in her honor held in Italy, France, and finally in 2004 at the Royal Academy of Art in London. In 2018, her painting "The Musician" was sold at an auction in New York for over $ 9 million. A year later, the painting "The Pink Tunic" went for $ 13.3 million. Lempicka's paintings are collected by Madonna, who used the artist's works in her famous music video "Vogue".

For the Polish audience, it meant that Łempicka's paintings were extremely difficult to bring to Poland. All the more praise for the organizers of the Lublin exhibition, who managed to borrow about 40 works from French museums as well as from private collections. No one knows when there will be an opportunity to see them again.

But the exhibition also makes one ponder over the interwar period. This peculiar time, when the slogan of modernity, was picked up by the communist camp, and on the other hand, the world of luxurious hedonism was also excited about it. If you look for a symbolic queen of the latter camp, it was undoubtedly Tamara Łempicka, born in Warsaw.

– Piotr Semka

TVP WEEKLY. Editorial team and jornalists

–Translated by Sally Jastrzębska

The exhibition "Tamara Łempicka - a woman in travel" will be open at the National Museum in Lublin until August 14, 2022. From September 14, 2022, it will be on display at Villa La Fleur in Konstancin near Warsaw.