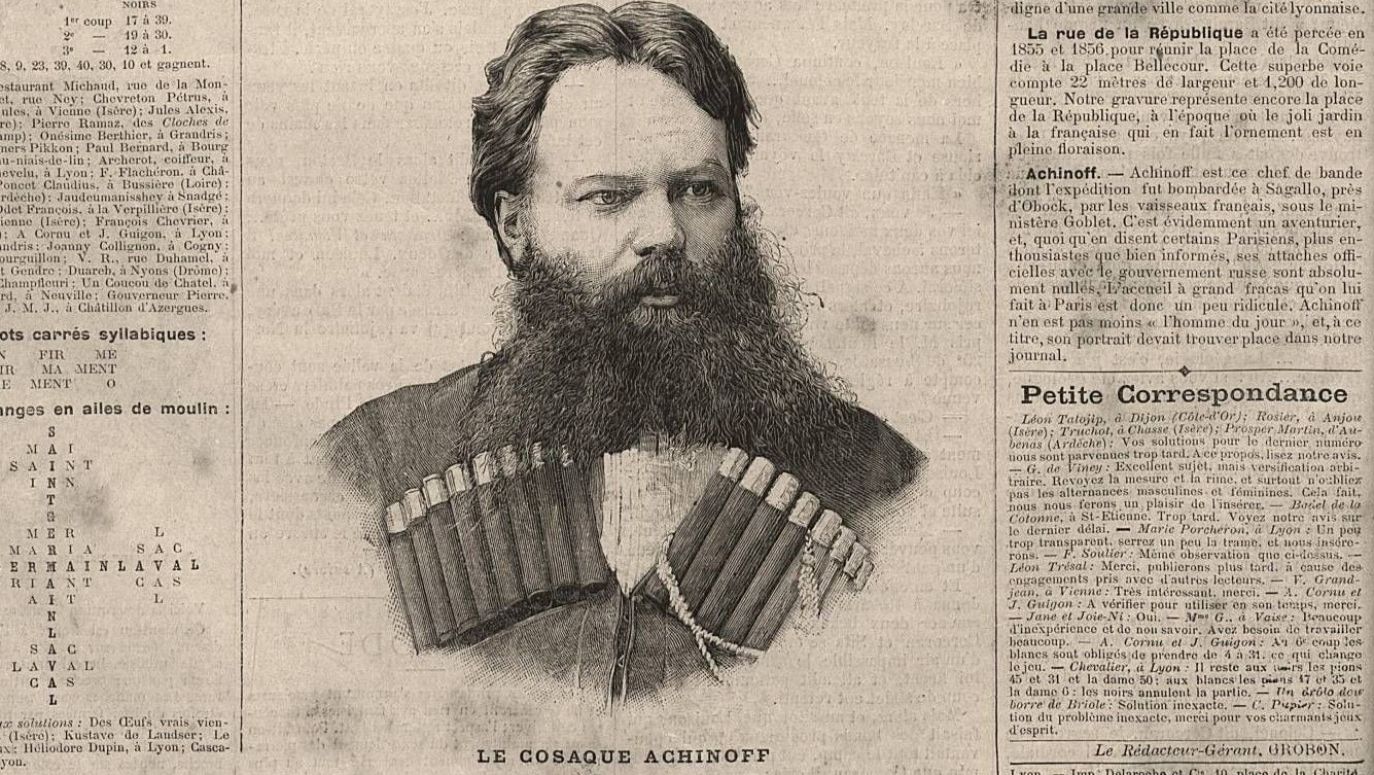

Alexander III granted an audience to Ashinov. Around the same time, the Tsar received a project that drew him even further into his plans. The proposal came from the governor-general of Nizhny Novgorod and an enthusiastic supporter of the adventurer. Nikolai Baranov called on the tsar to support the creation of the Russian-African Company, following the example of the colonial ventures of other European powers.

Ashinov presented a number of arguments in favor of Russian involvement in the Horn of Africa. First, a Russian presence on the Suez route would pose a threat to Britain. Second, the advantageous position at the mouth of the Red Sea could be used as a bargaining point to promote Russian interests in the Bosphorus. Finally, the Russian port in the Gulf of Tadjoura would provide a starting point from which contacts with Christian Abyssinia could be developed. Russia could strengthen it and rely on this country to oppose the British.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

However, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs opposed the African "adventure". The head of imperial diplomacy, Nikolai de Giers (son-in-law of the influential politician Alexander Gorchakov) and his men were concerned that the European powers might react unfavorably to Ashinov's plans. So the Chief Procurator of the Most Holy Synod, Pobedonostsev, figured out how to minimize the risk. Ashinov's expedition was given a religious dimension. Metropolitan Isidore blessed the project and ordered that a priest be designated who would officially lead the mission.

The choice fell on Father Paissi. The clergyman, who came from the Orenburg Cossacks, had taken part in military campaigns in Central Asia in the years 1840-62, and had then spent many years in a monastery on Mount Athos. Apparently, he was familiar with oriental languages. The official goal of the expedition was to reach Abyssinia and strengthen religious relations with Ethiopian Christians.

Despite the warnings of Ministry of Foreign Affairs officials, Alexander III, clearly fascinated by the prospects of initiating expansion in Africa, was more inclined to the heed the position of the "hawks" in trade and church circles. After defeat in the Crimean War, the government of the Russian Empire increasingly promoted its interests in the Middle East. The government began to use Slavophile organizations such as the Slavic Society and the Palestinian Society for purely political purposes. Religion increasingly served as a cover for the Russian state's foreign policy maneuvers.

For his part, Alexander III, albeit unofficially, made it clear that there should be financial backing to help organize Ashinov's expedition to Africa. The emperor did not want to spoil relations with Italy and France, which claimed the territories of modern Eritrea and Djibouti. The Palestinian Society, led by the Tsar's Slavophile brother, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, raised funds that enabled Ashinov to set out for Africa again.

However, it was evident from the onset that the aim was about strategic, not religious, interests. The Naval Archives preserved an order to the commander of the gunboat "Manchurian" from November 11, 1888, directing him to carefully examine the Gulf of Tadjoura and report to the Ministry of the Russian Navy whether "it is a reliable shelter for ships and to what extent it is inaccessible to the enemy." Matters became complicated when Admiral Shestakov died ten days later and Admiral Vasily Chikhachov became the new Minister of the Navy. He rescinded his predecessor's promise to Ashinov that the gunboat "Manchurian" would escort the expedition to Africa. Faced with this, Ashinov had to go to Odessa in October to charter a vessel that would transport the expedition.

The steamer "Kornilov" sailed to Alexandria on December 10, 1888. How many brave men sailed with Ashinov? The information is contradictory. Most often, the given number is 150, although the number 175 also appears. In the notes of one of the expedition participants we read that it included a religious mission of 40 people, as well as a military unit of 150 people. In addition to the so-called free Cossacks on board, there were residents of Odessa, several Ossetians, several Terek Cossacks, three St. Petersburgers and two Kharkovians.

Who were they? A dozen or so intellectuals, as well as a carpenter, a builder, a blacksmith, a locksmith, a gardener and former soldiers with their wives and children. The volunteers were divided into six units commanded by former military personnel. In Alexandria, they switched from the "Kornilov" to the Russian ship "Lazarev". In Port Said, Ashinov chartered the Austrian "Amphitrite", and this was the vessel that delivered the expedition to its destination. On January 6, 1889, they entered the Gulf of Tadjoura.

Get that bastard out of there…

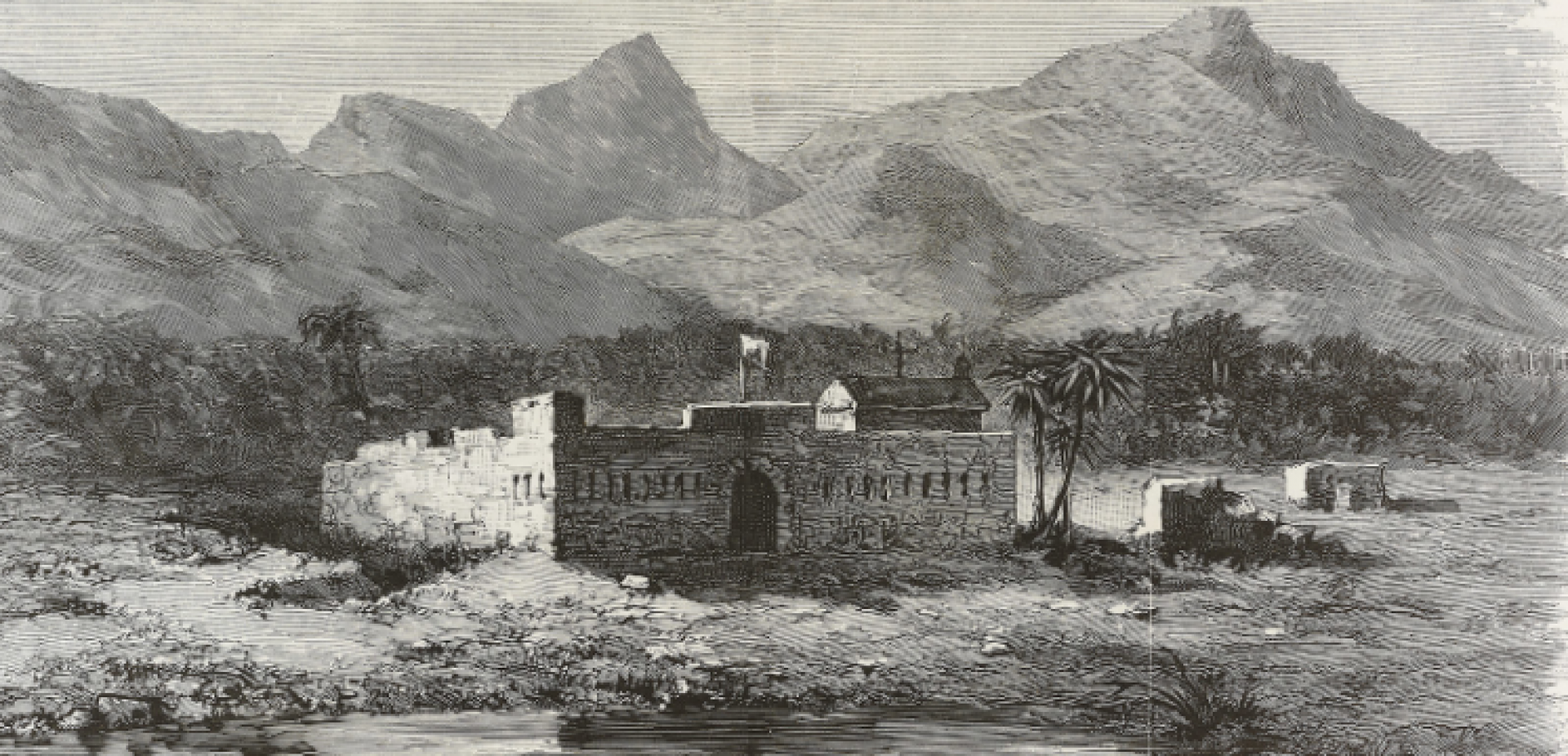

The expedition met with the Cossacks whom Ashinov had left behind during his previous visit. They also met with the Abyssinian clergy who had been awaiting the arrival of the colonists. According to the official version of events, the travelers from Russia then planned to go to Abyssinia. The formal ruler of these lands was Sultan Mohammed Sabeh, with whom Ashinov had established friendly relations during his previous visit. The Russians concluded an agreement with Sabeh and with Mohammed Leita, the chief of the local Afar tribe, that allowed them to occupy the abandoned former Turkish-Egyptian fort of Sagallo, some 40 km south-west of Tadjoura.

On January 14, 1889, the Russians took over the fort and raised the Russian flag above it. Ashinov announced the establishment of a settlement called "New Moscow", and the lands lying 100 versts (one verst equaled 1,066 m) along the sea and 50 versts inland were declared Russian. The colonists began to establish gardens and orchards (planting seedlings and seeds brought from their homeland) and they built houses. Soon a merchant ship was to arrive from Russia with supplies of food, weapons and iron.

However, the Slavophiles supporting Ashinov showed disastrous ignorance about the functioning of European colonialism, thinking that the occupation of land in Africa by a group of Cossacks would not arouse the suspicion of other powers. Both Great Britain and Italy were openly hostile to Nikolai Ashinov's plans from the beginning. Their diplomatic representatives in Saint Petersburg repeatedly made efforts to prevent the proposed expedition, which had been widely reported in the press for a long time. The idea of arms supplies to Abyssinia seemed equally disturbing.

But it was not London and Rome that were the real threat to "New Moscow". It seemed that as long as Ashinov was willing to recognize French sovereignty in the region, its authorities were willing to leave him alone and allow him to continue. However, when Ashinov suggested to French officials that he only considered local warlord Mohammed Leita as a partner, it aroused suspicions. Especially since it became clear that the religious nature of the expedition was a cover. The French officer who arrived in Sagallo demanded that the Russians leave the fort as quickly as possible. Ashinov refused. Since France was in good relations with Russia, the local representatives of Paris did not dare to take immediate action to expel the uninvited representatives of a friendly power.

At first, Alexander III, seemed unconcerned that Ashinov might provoke the French. However, soon he was receiving news about the self-proclaimed ataman's inappropriate behavior. These were coming from his ambassador in Paris as well as from naval officers. After a series of French protests, the Tsar made a decision: "It is absolutely necessary to remove this bastard Ashinov from there as quickly as possible... He only embarrasses us and we will be ashamed of his activities."

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE