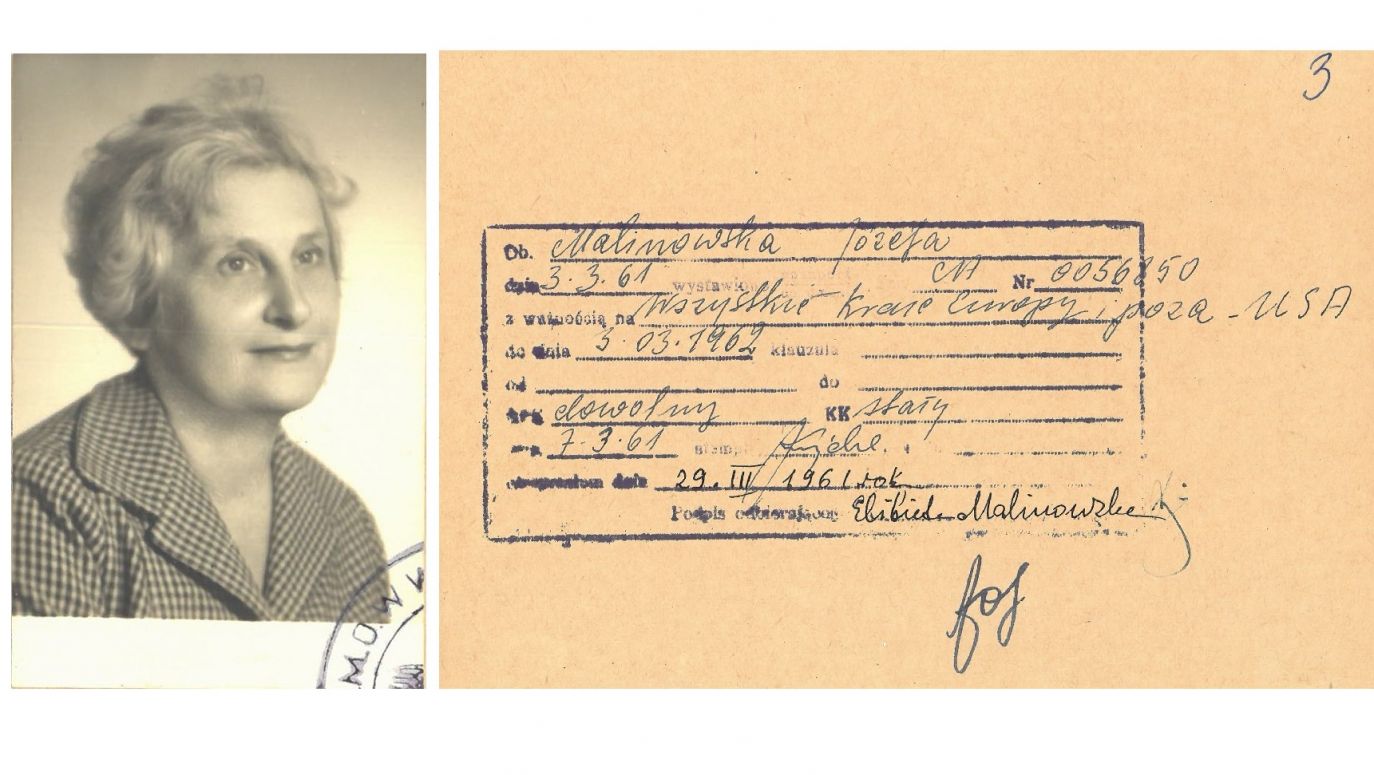

The description she gives confirms what we see in her passport photo: grey hair, dark eyes. She fills in the box: profession - painter. Next lines of data... Box number 16: current place of work (in full), address of workplace and position held, or other source of income. Malinowska writes: "I am dependent on my sister who lives with me". Stefania declares the same: "Elzbieta Józefa Malinowska aged 62, dependent on me".

George Dormont stated that he is employed as a sound engineer at the film studio Metro Goldwyn Mayer and intends to support his sister-in-law: "She is an artist painter".

The authorities quickly agree to the trip, in just three months, but then the procedure is prolonged. Stefania urges. She writes that they have nothing to live on, as she has given up her job and their flat, passed off for accommodation, "has been allocated to re-migrants from the Soviet Union, who are longingly awaiting the moment the premises are vacated, currently living in very difficult housing conditions".

George's purchased plane tickets are forfeited. Eventually the two ladies board the ship and set off for the New World. The shipping documents state that there are only three Polish women on board: them and Izabela "Czajka" Stachowicz, née Schwarz. A famous scandalist, a regular at pre-war raves and balls of knobheads at the Academy of Fine Arts, described by Witkacy, adored by the gentlemen, less so by the ladies. Before Władysław Stachowicz, she had two husbands: the first was the pre-war freemason, PPS sympathiser and sociologist Aleksander Hertz, and the second was the Warsaw architect Jerzy Gelbard. The war found her in Poland. She ended up in the Warsaw Ghetto, from which she managed to escape under the assumed name of Stefania Czajka. She wrote about her experiences in the book " I was saved by a blacksmith" (1956), and devoted a volume of poetry to the ghetto, with a foreword by Władysław Broniewski. The question is, had two of the three Polish women on the ship never met before? Izabella Czajka Stachowicz studied painting in Paris and blossomed in the artistic circles of pre-war Warsaw. Elżbieta Hirszberżanka was a member of the capital's artistic milieu at the same time, also studying in Paris. The paths of these women may have crossed.

It is certain that Dormontowa and Malinowska reach the United States via Canada. Thanks to this, we can learn that Elisabeth is 154 cm tall, with beady eyes and grey hair. The meticulousness of the immigration authorities is somewhat frightening.

Ignacy, Stefania, Elżbieta lived together the three of them in California. They changed addresses (the US electoral registers track them), phones. George changed jobs, then retired, Stefania was housewife and Elizabeth dependent on her. Then they were laid to rest together in the San Diego cemetery. First Ignacy Dormont died (18 June 1984), then Elżbieta in 1991. Stefania outlived her by five years. American records of the deceased state that Stefania was born on 1 August 1901. Her mother's maiden name was supposed to be: Malinowska. Father's surname: Staszewski. She died on 12 August 1996. And this is the only certain date.

A biography of Elżbieta Hirszberżanka can therefore be completed. She was born on 1 February 1898 - died on 5 December 1991. She is buried under the name Elżbieta Malinowska in San Diego.

"She lived almost a hundred years. Until the end under an occupation name. On the Aryan side," comments PhD Renata Piątkowska.

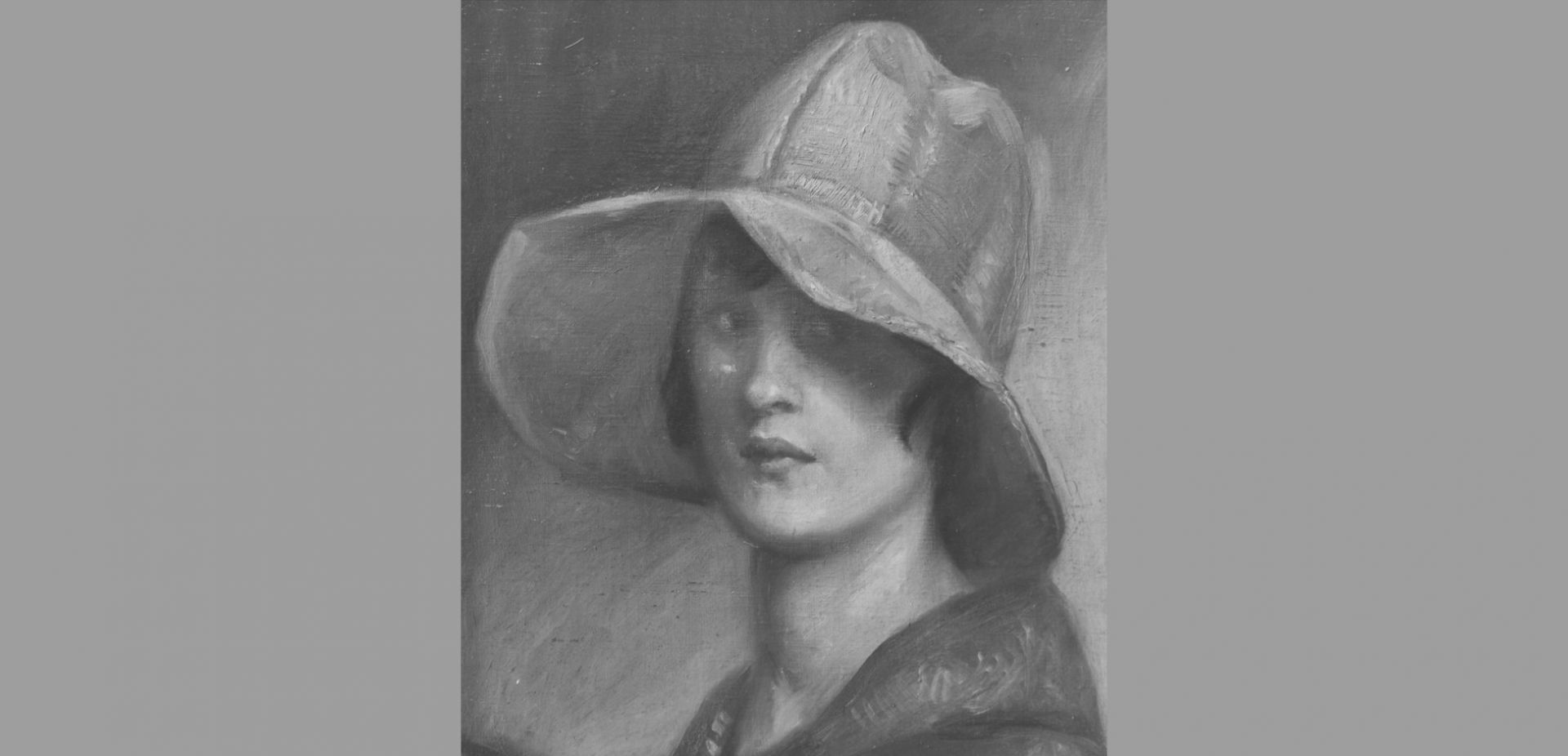

And a painter to the end. The inscription on her tombstone reads: "artist painter", but will we ever know her post-war works? And do they even exist?

– Beata Modrzejewska

– Translated by Tomasz Krzyżanowski

TVP WEEKLY. Editorial team and jornalists

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

They were accepted. They had no trouble paying for their studies. They came from bourgeois families. Only Litauerówna, a Wilnian, was an outsider. Gizela and Elżbieta were born and raised in Warsaw.

They were accepted. They had no trouble paying for their studies. They came from bourgeois families. Only Litauerówna, a Wilnian, was an outsider. Gizela and Elżbieta were born and raised in Warsaw.