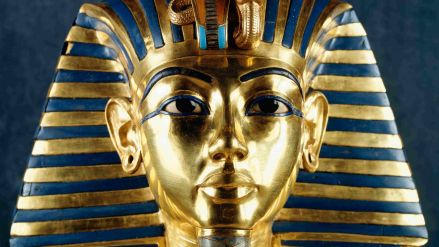

From “The Twelve Caesars” we know an anecdote about a die that “has been cast” or money that does not stink.

see more

You have swapped a career as an antiquities scholar for a representative of the "pop history" trend or even a Youtuber. Which is better?

Everything has its good and bad sides. The great thing is that as a YouTube content creator and social media maker, I can cover a lot of topics that I could not explore as a researcher. As a researcher, you focus on a specific area, research it thoroughly, write a dissertation or publish a book. I used to do that, but after a while, it became tiring and limiting. Now, I can deal with everything, not just a narrow area. My latest book, "Naked Statues," consists of 36 essays from very different areas of ancient history that I could never fit into a classic history book. This also allows a more creative approach. Another difference is the audience, which has become huge. As a lecturer, I used to speak to an audience of a few dozen; now I am seen by more than a hundred thousand, sometimes several hundred thousand people every few days. It’s very rewarding, just imagining a lecture hall of this size where everyone present is interested in ancient history.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE  Sometimes I feel that everything about this story has been written and rewritten many times. The ancient texts have already been explored since the Renaissance, what is there left to discover?

Sometimes I feel that everything about this story has been written and rewritten many times. The ancient texts have already been explored since the Renaissance, what is there left to discover?

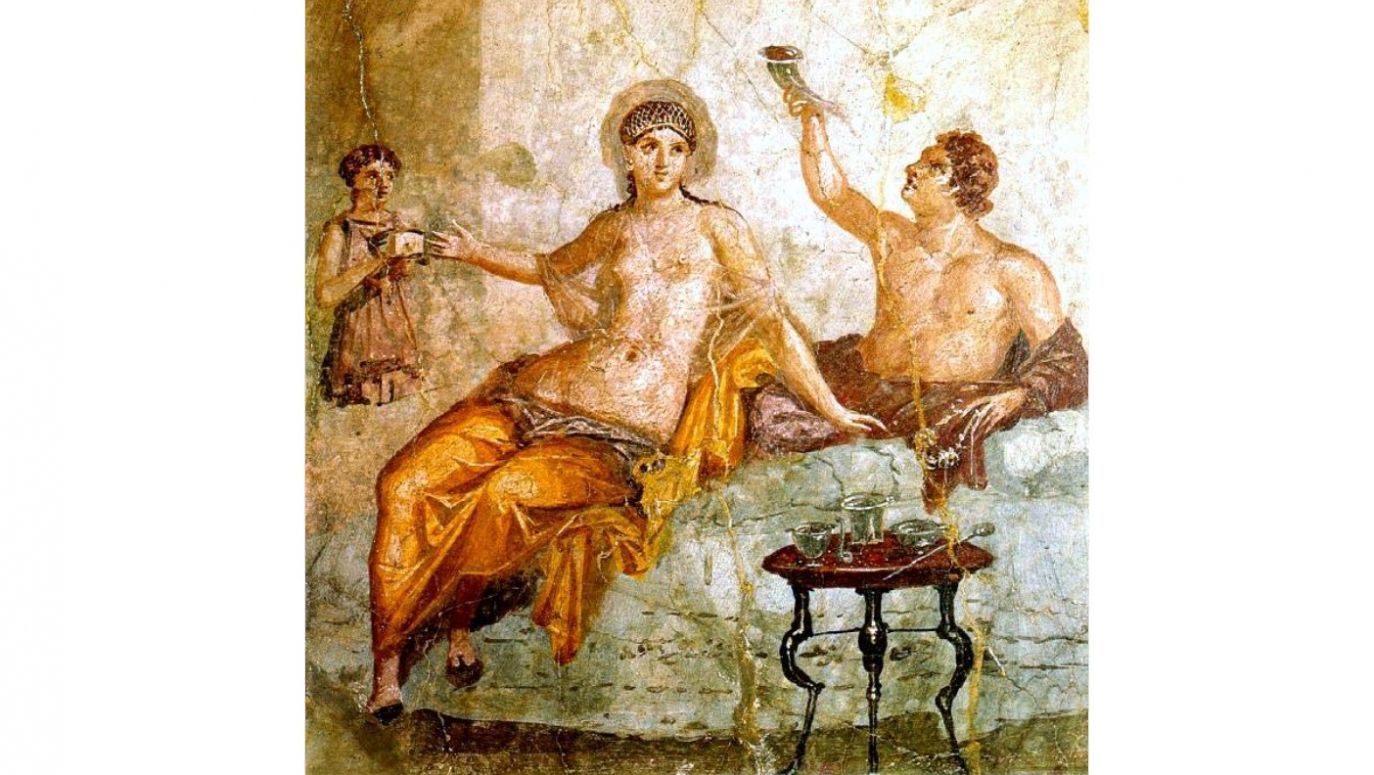

Indeed, it may seem so. Historians of antiquity often refer to texts that we have been reading for hundreds of years, such as the histories of Herodotus or Tacitus. Their works were already in widespread use more than five hundred years ago and have already been widely reproduced and interpreted. But when it comes to studying Roman everyday life, we can always come across something new. The countless Egyptian papyri discovered since the late nineteenth century shed new light on the ancient world, including details of people's lives; there were even court minutes and tax records. So we shouldn’t assume that we already know everything we ever will about the common people of antiquity. Just recently, fragments of the great Greek poet Sappho were discovered. Archaeologists come across new inscriptions, discover fragments of local stories. Most interesting, however, are the finds at Herculaneum, a library flooded by volcanic debris after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Charred scrolls can now be "unwrapped" by 3D scanning, which could give us access to an incredible number of ancient works.

What would be the most valuable discovery we could come across if we traveled in a "time machine"?

As a Roman historian, I would love to finally read the never-discovered works of my favorite authors, such as Tacitus. He is an outstanding historian of antiquity, but we only know of three of his works that were found during the Renaissance. I would like to see the rest of Tacitus discovered. There are still tragedies and comedies that we know were written, but we do not know them because they were lost in the Middle Ages, like Ovid’s Medea. Above all, we also do not know the true story of Alexander the Great, but only accounts written down centuries after his death. What if we had come across the records of his companion Ptolemy, who assisted Alexander in his expeditions and battles against the Persians? That would be fascinating.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE