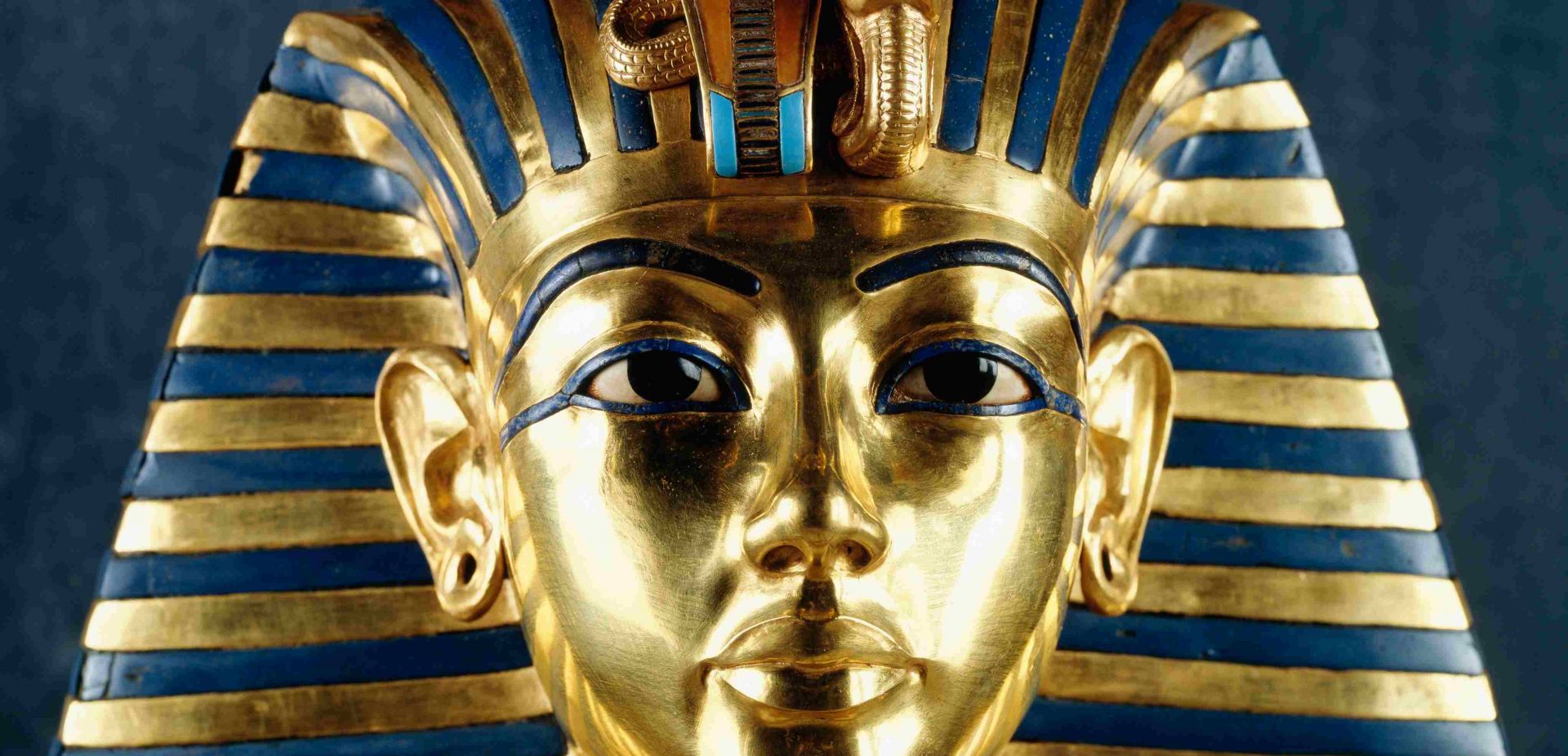

In ancient times, silver (imported from afar) was much more valuable in Egypt than locally sourced gold. While gold was considered the "flesh", silver was identified as the "bones" of the gods. This explains why the nominal value of the silver coffin of Psusennes I, now called the "Silver Pharaoh", was many times higher than the value ascribed to Tutankhamun's "mere" gold coffin.

The mummy of Psusennes I completely disintegrated in his silver coffin, but Montet, just as Carter once had, could look at the pharaoh's face, thanks to the fact that his splendid golden death mask survived. Many Egyptologists considered this mask to be much more beautiful and valuable than that of Tutankhamun's. Certainly, it is more refined, harmonious and expressive artistically.

A lot of priceless jewelry, ornaments and objects were also found in the tomb, yet today the tourists rushing through the Cairo Museum to the cabinet displaying Tutankhamun's mask, often fail to as much as look into the nearby room where the treasures from the tomb of the "Silver Pharaoh" are shown.

Grand tour of the mask

For long after World War II, no one paid any attention to Egyptian antiquities. It was only in 1960, when the construction of the Aswan High Dam on the Nile began, that Egyptian authorities decided to resort to cultural diplomacy and remind the world of Tutankhamun's treasures.

This stemmed from the fact that the plan to create the Lake Nasser reservoir threatened to flood many monuments dating from ancient Egypt. Under pressure from archaeologists from around the world, Egypt managed to convince UNESCO to carry out an unprecedented and very expensive operation to save these monuments. As a result, the 24 largest were moved to higher places (the most famous being the Abu Simbel temple complex), or given to countries that participated in this operation.

Key to mobilizing UNESCO to action was the support of the United States, France, Japan, Great Britain, the Soviet Union and West Germany.

Treasures of Tutankhamun set off on a world trip. Initially, in 1961, 34 small objects from the tomb were shown in Washington, with Jacqueline Kennedy, wife of the president, opening the exhibition.

The first major success did not take place until 1967, when the golden mask of Tutankhamun arrived in Paris, triggering a huge sensation. Then it went on display alongside many other treasures from the tomb in Tokyo and London. From November 1976 to April 1979, the exhibit toured six different US cities, starting with the National Gallery in Washington. The mask, along with other treasures, was transported from Egypt to the US aboard the US warships USS Milwaukee and USS Sylvania.

The first US exhibition in 1976 was opened by President Jimmy Carter and attended by Elizabeth Taylor who had played Cleopatra in the unforgettable film of the same title. Also present were other Hollywood stars including Robert Redford and Rex Harrison. Pop art king Andy Warhol also dropped in. People queued for tickets for hours. In Washington alone, the mask was seen by almost a million people, a number that was exceeded by the 1.2 million who viewed it in New York.

Such was the sensation established by the "Treasures of Tutankhamun" exhibition in the USA that it is considered to be the first "blockbuster" of its kind in the country, i.e. a cultural event with a spectacular box office success (the latter a term usually reserved for hit movies). Thereafter the mask travelled to Canada, the Soviet Union and West Germany, helping further the renewed global fascination with the treasures from Tutankhamun's tomb that has lasted to this day. The opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza is expected to fuel it even more.

– By Krzysztof Darewicz

TVP WEEKLY. Editorial team and journalists

– Translated by Agnieszka Rakoczy

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE