He paid for it not with his head, but with his freedom. According to some sources, after the defeat of the Insurrection, he was sent to Siberian exile, according to others – only to the prison in Vilnius, where he still spent over a year. At the same time – it was not unusual for the nobility of the most distant borderlands, even in the years of repression and the collapse of the country, to gravitate around the strongest political, educational and economic center of north-eastern Europe, which at that time was St. Petersburg. Tadeusz’s mother, Amelia, sent her son to the Cadet Corps there – and whoever may be indignant at this, let them remember how many generations of borderland nobility were educated there, all the way up to the young Józef Czapski a little over a century later. Was a boy supposed to waste his time lodged in Vilnius?

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

The beginning of Tadeusz’s career was therefore predictable: he was a cadet, a cornet (slightly lower than an ensign) in the campaigns against Sweden and France in the war of 1806, wounded even at Friedland, for which he was awarded the Order of Saint Anne (third degree). Or for reprimands received for a romance scandal or for writing satires: first, a month’s imprisonment in Kronstadt, then, quite unpleasant service in a dragoon regiment, and finally, dismissal from the army with the fairly low rank of lieutenant.

And then, the first Bułharin about-face took place: almost like his more famous namesake in book ten of the Poem [

–Mister Thaddeus by Adam Mickiewicz], he saved himself by crossing over the Nemunas river and joins the ranks of the Polish army. Did he really traverse as far as Spain with supplies for the Legion of the Vistula [Poles serving Napoleonic France], under the orders of Józef Chłopicki? I wouldn’t be so sure of that, but his participation in the epic French invasion of Russia in 1812 is confirmed. Apparently, he was even recommended for the Legion of Honor for heroism at Mozhaysk, but let’s put this with the story about Skenderbeg. Certainly, however, he crossed through the entire route, he was even wounded again – for the Emperor – near Chełm and again in the Battle of Leipzig. However, he was taken prisoner by the Prussians and in 1814 he was extradited to Russia.

Desertion came to nothing

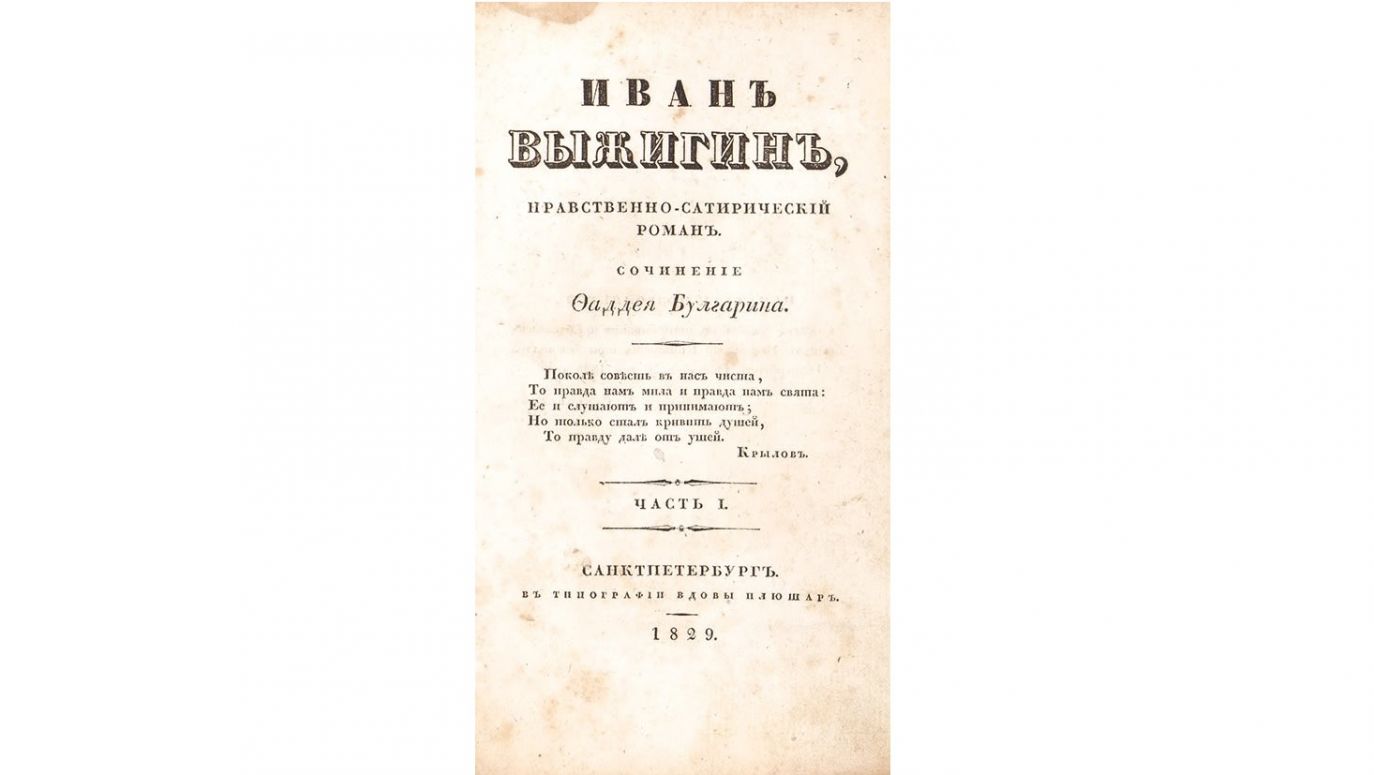

In fact, he should have been sent for penal service as a deserter. However, formally speaking, he was dismissed from the army, and in 1811, when Tadeusz agreed to serve, Napoleon was still formally an ally of the Tsar – it all came to nothing. Tadeusz, deprived of property (a small estate near Minsk did not survive the war of 1812), wandered: he frequented Warsaw and Vilnius, he wrote here, he wrote there – sometimes a note to

–The Vilnius Journal and sometimes a satire to

–Tabloid News. However, it was impossible to make a living from this, or from managing his uncle’s estate – so in 1819 he moved to St. Petersburg.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE