Social and community life of Polish authorities in exile. London vicissitudes of emigration presidents and prime ministers

16.11.2022

The White Eagle club in the district of Knightsbridge evolved from a respected culture center to a second-rate bar and almost a gambling den with gaming machines. Poles stood them willfully, they showed no respect to English regulations considering the sale of alcohol. Vodka was available there 24 hours a day.

On November 12, 2022 three Polish presidents in exile: Władysław Raczkiewicz, August Zaleski and Stanisław Ostrowski – will be buried in the Temple of Divine Providence in Warsaw. The ceremony will be broadcast by TVP1 and TVP Polonia, on Tuesday from 3 pm.

The end of WWII meant a number of changes for Polish authorities in London and, more widely: for the Polish emigration as such. On the one hand – political ones – after Stanisław Mikołajczyk joined the Warsaw government, dominated by communists (Provisional Government of National Unity), US and UK withdrew their recognition of the Tomasz Arciszewski cabinet. Not only did it imply the lowering of its international position but also the loss of English subsidies followed by necessary job cuts within the government administration or, for instance, the move of Polish clerks and military men to less prestigious buildings, etc.

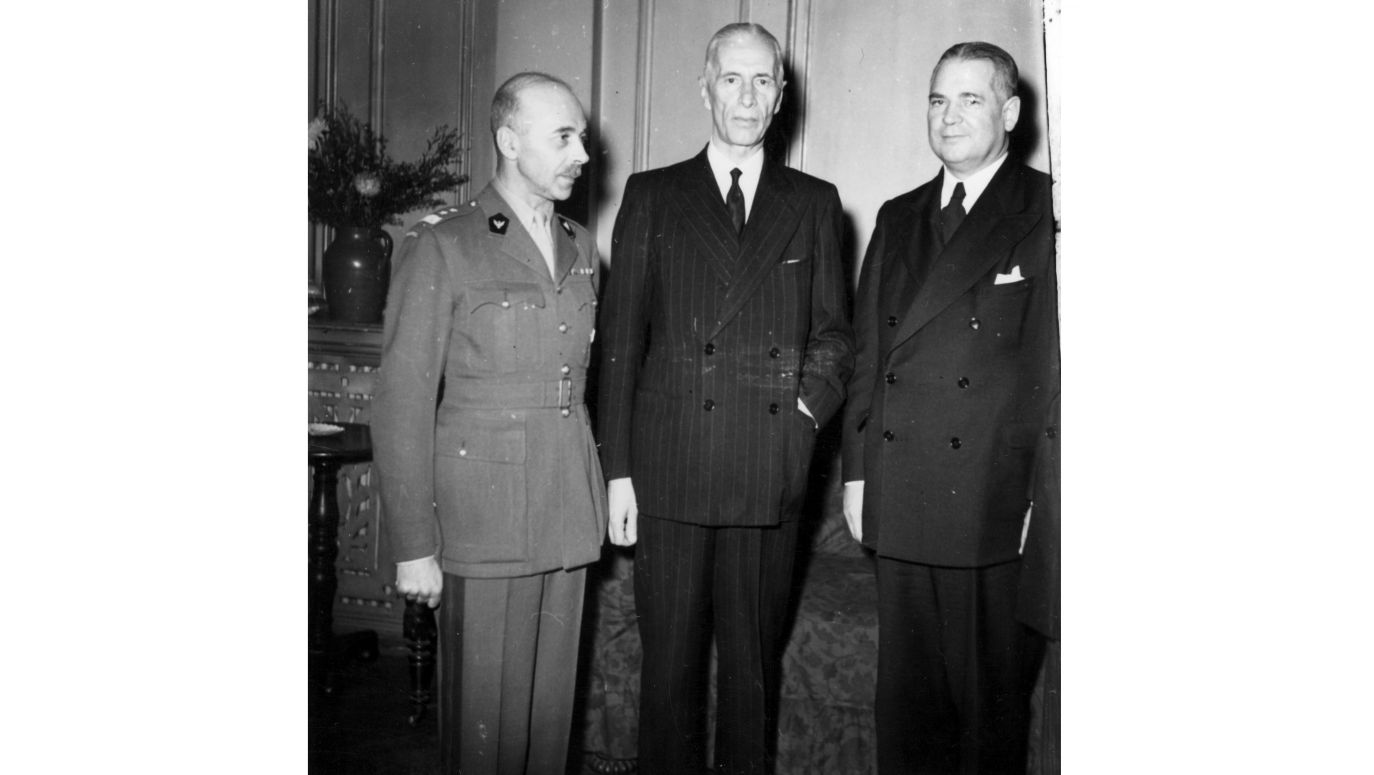

On the other hand, political changes led to social consequences – those who lost previously held positions, as well as Polish newcomers from other Western countries (mainly soldiers of the Polish Armed Forces) had to build their lives from scratch, find a job and place to live, mostly on poor conditions. Significant is the conversation from summer 1945 between the ex-minister of foreign affairs (and future president) August Zaleski and the current ambassador in the Arciszewski government.

“– And that’s how it has all ended. Zaleski nodded his head. Then the Englishman interjected[…] – I know a family in the countryside that would eagerly hire a Polish service. Then Zaleski replied: – As far I am concerned I could only be a cellar master because I am too old to be a stableman or equestrian”. There was little exaggeration in it, the vast majority of émigrés, regardless of them being workers, peasants or educated people was now undertaking physical work. Big names weren’t absent from this milieu – let’s take generals as an example. Stanisław Sosabowski became a storeman, KordianZamorski worked as a lift attendant, Władysław Bortnowski hired himself as a nurse in a Polish hospital and Stanisław Maczek found employment as a bartender.

It was for the authorities in exile to take care both of them and thousands of other Poles. In relation to which the government came to the conclusion to make an agreement with the British and consented to form the Polish Resettlement Corps (PKPR – Polski Korpus Przysposobienia i Rozmieszczenia). All soldiers of the Polish Armed Forces based in the Isles could join it and the service in PKPR (max. 2 years) enabled them adapt to British conditions. Over this period they had been learning English, taking professional courses and didn’t have to bother about the money (they collected the pay and their families could occasionally count on financial support). After the service they could choose one of four options: return to communist Poland, departure to another country, enrolment in the British army or work on the Thames as a civil person.

Emigrant calendar of a patriot

A lot of time has been devoted to politics, but it would be simplistic to reduce the activities of the president or the government to this alone. All the more so since it was up to Wladyslaw Raczkiewicz, Tomasz Arciszewski and their successors in the first place to keep the spirit of Polishness in their compatriots alive.

For example, through patronage and presence at patriotic celebrations – it is worth starting a review of them from the 3rd May Holiday. Even in 1946, a modest celebration took place but a year later it was organized on a much larger scale. With the participation of, inter alia, Arciszewski and general Anders, a ceremonial academy took place at the Convay Hall in London, where Zbigniew Stypułkowski was one of the speakers.

A pre-war national activist who was captured by the Soviets during the war and almost shared the fate of the Katyń officers stated, among others, that “the celebration of 3rd May Holiday has always been an opportunity to manifest the will of the Polish nation to exist independently and [its] inseparable ties with the ideals of the Western civilization”.

This tone was repeated in subsequent speeches, and the celebration of the Constitution every year allowed our authorities to remind the world and fellow countrymen of Poland as an integral part of the West for generations. The celebrations organized on the occasion of the 1st (beginning of the defense of Lviv anniversary) and November 11th were of a more modern character.

In 1948, 30 years had passed since these events, and Polish London treated the celebration as an opportunity to manifest the rights of the Republic of Poland, on the one hand to the Borderlands, and on the other to sovereign existence. Both anniversaries were celebrated primarily in the cultural and social center of exile – The Polish Hearth (Ognisko Polskie – we will return to it later), where academies were held with the participation of, among others president Zaleski and prime minister, general Tadeusz Bor-Komorowski.

Although history topics (lectures on the economy & culture of the Second Polish Republic, speeches given by defenders of Lviv) filled a large part of the celebration, there were also references to the present day – for example discussions about Polish-Ukrainian relations. And we must remember that at that time almost all emigration adopted the stance that the 1921 “Riga” borders were inviolable ...

Let us add that gradually a “patriotic” calendar was formed among the emigrants, which included the most important anniversaries of the modern Polish history: August 15, September 1 and 17, November 1 and 11 plus May 3. holy masses, parades, galas and lectures - all this made up the obligatory repertoire of each celebration, and over time the group was joined by May 18 – the Battle of Monte Cassino anniversary.

With time and the assimilation of Poles in the United Kingdom, the number of participants was shrinking, but the president and ministers could always be counted on. Also during the celebration of the 1000th anniversary of the baptism of Poland (1966), which London celebrated exceptionally loudly (including a mass, a parade of military banners and a historical spectacle – all at the White City stadium with the participation of ca. 40,000 people!).

London Wawel and the police at Orzeł's

Politics is politics, academies are academies, but representatives of the Polish authorities also led a social life. The No.1 place when it comes to meetings of the elite was Ognisko Polskie, also known as the “Wawel of the Emigration” or “London Wawel”. Established in 1940 as a club for Polish soldiers, after WWII it became a social, cultural and entertainment space.

When one of the presidents or ministers wanted to read, he could, for example, use the local reading room. The hungry were attracted by bars and restaurants serving homely food, while in the evening, “Ognisko Polskie” tempted with a rich offer: there were meetings with authors, concerts, lectures, cabarets – “Afternoon tea by the microphone”, a total of over 300 events a year. Between debates, speeches and celebrating various celebrations, the most important politicians could also stretch their bones on the dance floor.

This state of things lasted until the 1950s, when “Ognisko” underwent a transformation. While so far the services of various organizations based here had been eagerly profited from by ordinary Poles (for example, attending English or sewing courses), at that time this place morphed into a “public social and political salon of Polish London”. Anyway, one thing hadn't changed – one of the tables was still at the exclusive disposal of general Anders, who sat here every Thursday. Sometimes alone, sometimes in company, he would then have a brief respite...

Meanwhile, moving out of “Ognisko” did no good to many Polish organizations. Over the years, more and more voices have been raised on their part about the need to restore one central center of the Polish community on the Thames. A natural solution in this situation would seem to return to the former seat, but in this case the saying that you do not enter the same river twice has proved true.

Polish organizations decided to build a new building that would emigrate the Emigration – the Polish Social and Cultural Center (POSK – Polski Ośrodek Społeczno-Kulturalny) was opened in 1974. It quickly fulfilled its role, housing a number of social and cultural associations, cafés, restaurants, a theater hall, as well as the Polish Library and the Polish University Abroad in London (PUNO – Polski Uniwersytet na Obyczyźnie).

Trust ended for Polish officers with bullets in the back of their heads.

see more

Apart from “Ognisko” and POSK our top politicians would met, inter alia, at the Polish Combattants’s Association (aka Dom Kombatanta – The Veteran’s Hall) and the Polish White Eagle club. By the way the latter is associated with one of the biggest scandals in the history of post-war emigration. With time, the club evolved from a respected culture center (the former seat of the Marian Hemar Theater and the editorial office of Dziennik Polski and Dziennik Żołnierza) to a second-rate bar and almost a gambling den with gaming machines. Poles stood them willfully, they showed no respect to English regulations (e.g. those regarding the sale of alcohol – it was available practically at any time), so they finally got involved – the police raided the club. And this was exactly when President Zaleski visited here.

Long live the (Polish) ball

Sources remain tacit as to the president’s reaction to the sight of the officers, we know more about the fate of “Orzeł”. Unfortunately, they were not very happy – some time later, in January 1954, a fire broke out in the club, which turned out to be final nail in the coffin of this temple. In March 1955, the place was taken over by the British, and the Poles had to look elsewhere for their culture.

For example, in theaters, and fortunately there were many of those in Polish London. One of the most important – the Dramatic Theater of the 2nd Corps (later known as the Juliusz Słowacki Polish Theater and the Polish Theater ZASP – editor's note) – offered both a more serious and lighter repertoire, there were also several other theaters, and artists specializing in cabarets and revues remained in reserve.

Thanks to the latter, the audience, including politicians, could feel like they were in pre-war Warsaw. Especially that the atmosphere in the hall was taken care of by such announcers as Marian Hemar or “Pole humoris causa” – Fryderyk Jarossy, a Hungarian born in Graz, Austria, and who considered himself an Austrian.

It was fun at events that, although organized once a year, would be remembered for a long time – New Year's Eve balls. From the 1950s, the attendance reached at least several hundred people, the émigré elite also enjoyed themselves at carnival balls organized by Polish associations. For example, the event of the Association of Polish Technicians (Stowarzyszenie Techników Polskich) in 1955 attracted 825 people. In turn, the carnival party under the patronage of the combined forces of Technicians and the Association of Polish Doctors Abroad (Związek Lekarzy Polskich na Obczyźnie) in 1960 attracted the attention of over 500 people.

When reviewing Polish London events, it is also impossible to ignore the annual “garden party at the Anders’. Paying a visit to the general and his wife was a must for both politicians and artists, unless someone was in conflict with the winner from Monte Cassino – then he was considered persona non grata.

That was the example of August Zaleski. When in 1954, contrary to his promises, after the end of his term in office, he didn’t resign from the post of president, the commander of the 2nd Corps created a competing, unconstitutional center of power – the Council of Three. Anders and Zaleski stood on both sides of the political barricade, and such disputes naturally translated into social relations. The conflict could not be resolved until the death of the general in 1970, and the political reconciliation of emigration took place only after Zaleski’s departure two years later.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Finally, a few words about the spiritual life of the political leaders in exile. Anders and Zaleski might not like each other and dragged themselves through the mud via their supporters, but every Sunday at 1 pm they visited the same place – the Basilica of the Oratorian Fathers in the “Polish” part of the Kensington district. Until the beginning of the 1960s, it was this church that was the center of the religious life of emigrants, and at the same time served as a bastion of Polishness so to speak.

Finally, a few words about the spiritual life of the political leaders in exile. Anders and Zaleski might not like each other and dragged themselves through the mud via their supporters, but every Sunday at 1 pm they visited the same place – the Basilica of the Oratorian Fathers in the “Polish” part of the Kensington district. Until the beginning of the 1960s, it was this church that was the center of the religious life of emigrants, and at the same time served as a bastion of Polishness so to speak.