In the meantime, he became Piłsudski's trusted man, used by him for various secret missions. The following episodes testify to their relations at that time: in 1915, when the Commander was looking for an emissary who would appear in Warsaw before the German troops entered and provide his people in the capital with instructions, he chose Boerner. In turn, when in December 1915 the Austrians expelled Ignacy from the army for his involvement in politics, the brigadier defended the subordinate and had his dismissal withdrawn. So when Piłsudski inspired the so-called oath crisis (July 1917), Boerner knew well which side to side with. Like others, he was interned by the invaders in Beniaminów. Moreover, he received a dubious honor (although he would probably be proud of it) and the German and Austro-Hungarian military placed him on a blacklist of dangerous officers. As a result, he stayed behind the barbed wire until June 1918.

Mr. Lieutenant Peace

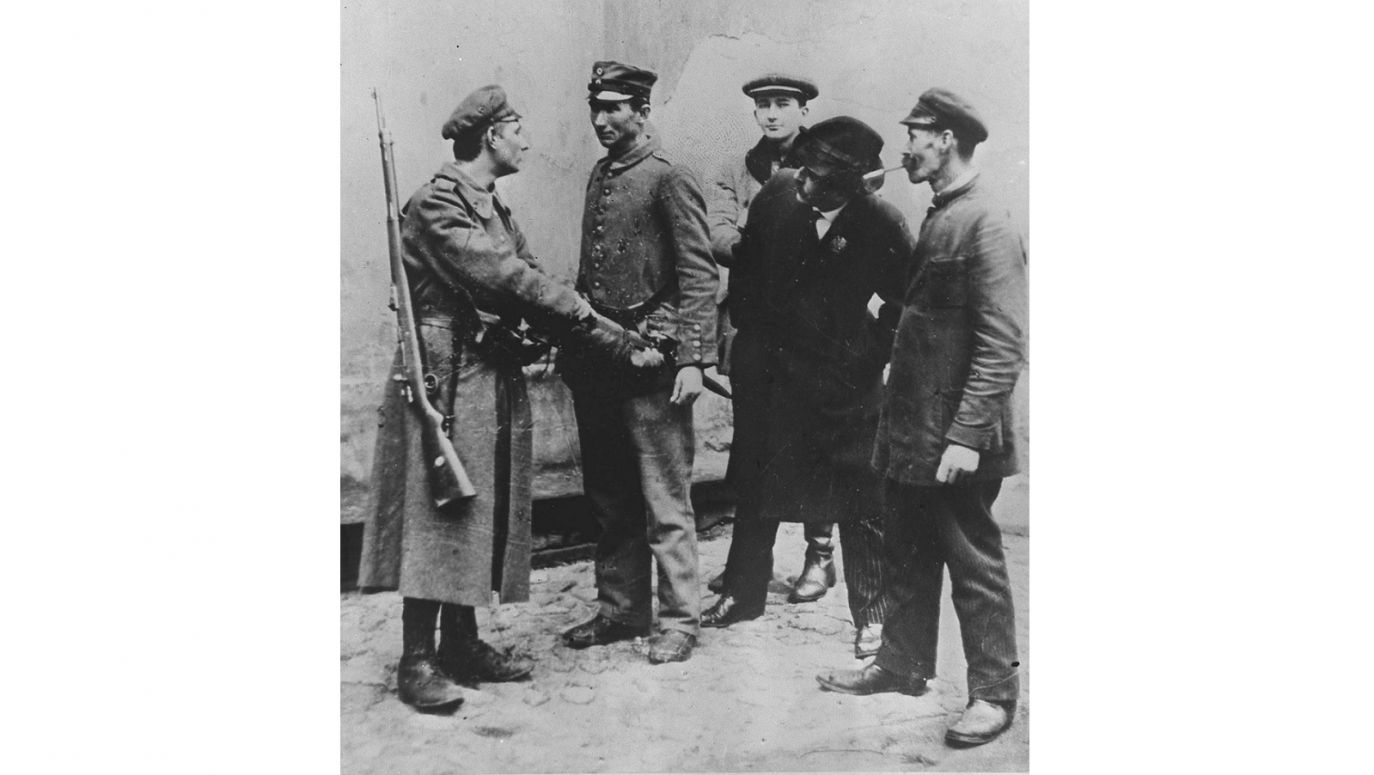

And it was him, whom in November 1918 Piłsudski appointed as a liaison officer for contacts with the Central Soldiers' Council. Because not only was Boerner his proven emissary (with time they got onto first-name terms; Piłsudski allowed at most a dozen or so people to become so intimate), but he also spoke German without a trace of a foreign accent and knew how to talk to Germans - he was aware that they wanted to go home as soon as possible. And above all, Boerner "had incredible self-confidence, could speak as if there was an immense power behind him, and was not easily disconcerted by any arguments."

Boerner coped smoothly with the first task that Piłsudski set before him - ensuring peace between the Council meeting in the Governor's Palace and the crowd of Poles outside. On his order, several dozen students formed a cordon around the palace. Boerner gave them weapons (the Central Soldiers' Council gave him 20 rifles), and at the end he went out to the crowd and appealed for an end to bloodshed. People dispersed.

Over the next few days, Boerner became the "chief fireman of Warsaw", extinguishing fires between Poland and Germany. On the one hand, he had to cool down the hot heads of the soldiers from the Central Council, who, hearing about the alleged murders of Germans allegedly committed by Poles, wanted to take armed revenge. On the other hand, it paralysed the intrigues of the German command, aimed at overshadowing Central Council and regaining control over the Warsaw garrison.

He also participated in Polish-German negotiations on the launch of railway transport, which had been suspended by the occupiers. Without this, there was no way to evacuate approximately 30,000 foreign soldiers and officials staying in the capital...

And what did November 11 look like from the perspective of Boerner himself? He spent the entire day, today considered symbolic of regaining independence, in the Governor's Palace, calming down German soldiers. He recalled: 'Every now and then someone would drop in [to the Palace], mostly officers dressed in civilian clothes, telling tall stories about the murders committed over the Germans. […] Every now and then I had to turn to them [Central Council soldiers] with the words: “Meine Herren! Blos Ruhe, Ruhe und nochmals Ruhe” (German: My Lords! Only peace, peace and once again peace). Due to this, he was nicknamed "Mr. Lieutenant Peace" among the Germans.

So much for the humorous accents, because when the sounds of shooting reached the building in the evening, part of the Council supported the immediate sending of a delegation to the Citadel with a request to the units stationed there to "come out and start bringing order with the force of bayonets and bullets." Boerner managed to nip the rebellion in the bud - he traveled around Warsaw with three members of the council to see for themselves that the Germans were safe in the city and any exchanges of fire were accidental.

A few days later, on the evening of November 16, upon hearing the news of the massacre in Biała and Międzyrzecz Podlaski, where several dozen POWs and Polish civilians died at the hands of German soldiers, he realised that it could be an introduction to the march of troops stationed beyond the Bug River (Ober-Ost) to Warsaw. He did not intend to wait for them: after Piłsudski's approval and with the participation of a representative of the Central Soldiers' Council, he began telephone negotiations with the Soldiers' Council in Brest (where the Ober-Ost headquarters were located).

All-night talks brought results: the Germans stopped the advance of their troops. And the threat was real - as the representative of Brest argued: "You [Germans] in Warsaw are in danger, so we decided to come to your aid. […] The railway lines will be staffed again. If the Poles agree, fine, if not, we will take it by force...

Years later, Boerner recalled November 1918 as the most important month of his life.

Let the words of General Stanisław Szeptycki, then chief of the General Staff of the Polish Army, serve as a summary. In 1921 he stated: "It was Mr. Major Boerner who, with his efficiency, tact, calmness, energy, in words - his entire personality, led to the peaceful evacuation of German troops from Warsaw - which success contributed in these difficult times to the possibility of starting work on the organisation of the state, the government and the army.

– Tomasz Czapla

TVP WEEKLY. Editorial team and jornalists

-translated by Maciej Sienkiewicz

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE