There have been generations of such intrepid voyagers. A history of geographical discoveries includes Pytheas of Massalia, a contemporary of Aristotle, who most certainly sailed to the British Isles, probably to Iceland, and perhaps (who knows?) even further. In "Peri Okeanos", he wrote about the blurring of the distinction between sea and land and the ice floes through which it was impossible to sail and the icy conditions which threatened to blanket the ship and its fittings. We know of several Vikings who sailed to the Kola Peninsula, including Ottar of Halogaland in the 10th century. What happened in the centuries that followed is shrouded in silence.

Trade with Russia is always profitable

Further attempts to storm the so-called Northeast Passage did not occur until the 16th century, and only then thanks to the rise of the powers of the European North: England, Sweden and the Netherlands. Richard Chancellor talked to Russian (Novgorod) merchants in sheepskin coats and furs. Steven Borough sailed as far as the Kara Sea. Willem Barentsz, the Dutch merchant/navigator who dreamed of Novaya Zemlya (Het Nieuwe Land), met his fate in the ice of Spitsbergen. The "Little Ice Age" of the 17th and 18th centuries was not conducive to migration along the northern shores of Eurasia. It was not until the optimistic age of steam and electricity that new attempts were made.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

And even then, drama was not in short supply. Think of the story of the American cruiser "Jeannette", which, under the command of George Washington De Long, got trapped in the ice north of the Bering Strait. For nearly two years, locked into an ice field, it drifted off the coast of eastern Siberia before eventually cracking apart under the crushing pressure of the ice. Most of the crew drowned in the icy waters of the Lena, ending their deperate efforts to reach the west, where they had hoped to find some semblance of civilization.

As often happens, out of tragedy came discovery. Three years had passed when the remains of the "Jeannette" -- including documents signed by De Long and the clothes of the crew members -- washed up on the west coast of Greenland, close by the settlement of Julianehaab. How did this come about? Fortunately, since teleportation had yet to be heard of, there proved to be only one explanation: the Northern Ocean's icefields do not circulate haphazardly but, rather, move in a circle, driven by ocean currents and the Earth's rotation. So the question arose -- was it possible that icefields were also on the move around and above the North Pole?

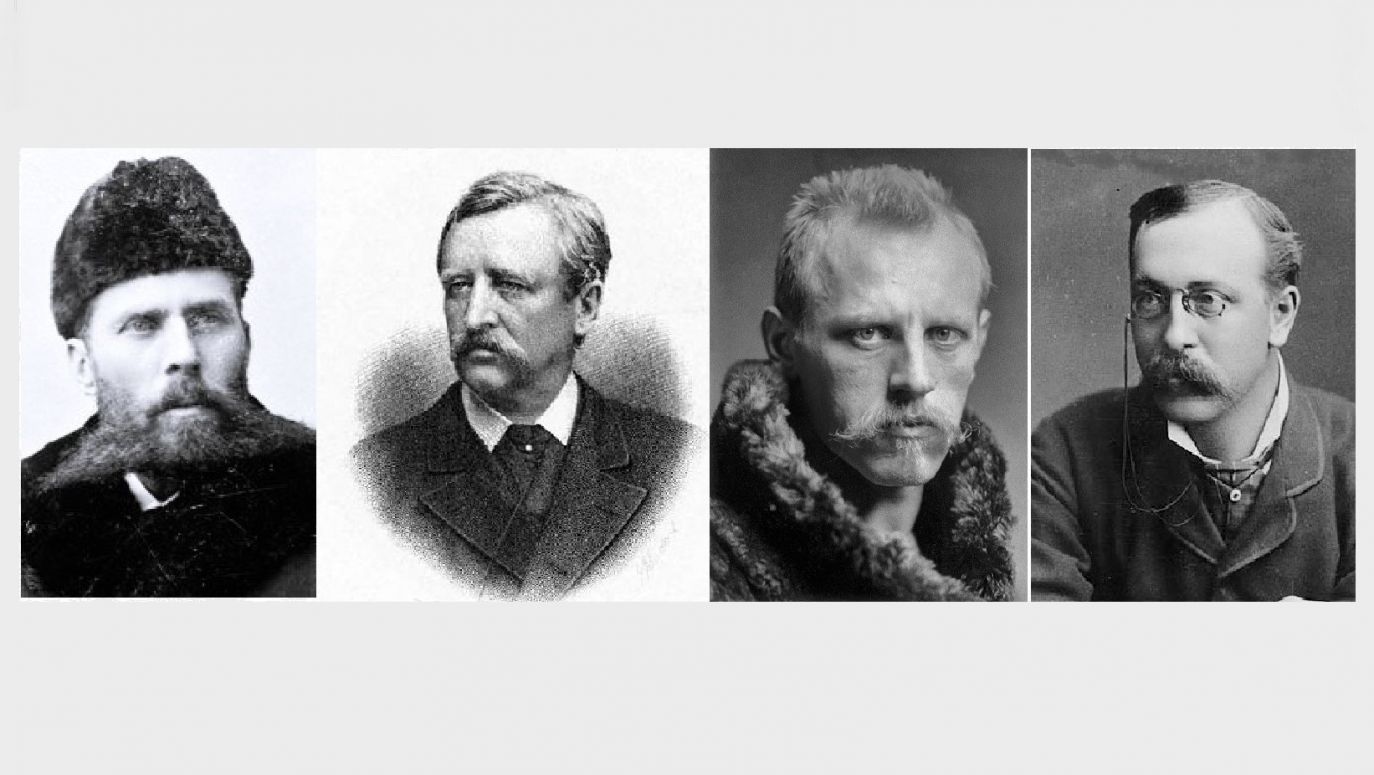

This hypothesis was to be advanced by twenty-something Fridtjof Nansen, a biologist, alpinist and skier, who worked at the museum in Bergen. He managed to convince a large part of the Norwegian elite and his peers about his hypothesis (which, slightly amended, turned out to be correct). That being so, Nansen postulated that it might be possible for a vessel to follow the drift of the ice field and venture far enough north to reach the Pole without becoming icebound.

"Fram" grows into the ice

Norway's aspiration to gain a symbolic advantage over Sweden, from which it was increasingly distancing itself, probably helped Nansen promote his theories. He appeared before the Geographical Society and Parliament, and thanks to public collections and budget subsidies, the sailing ship "Fram" was built in the years 1891-1893. Indestructible, resembling a nut shell, it was intended to sail into the ice fields where "Jeannette" had been destroyed. On October 5, 1893, the "Fram" found itself surrounded by ice at Cape Chelyuskin. It was to remain stuck in the middle of the ice field until the end of the month.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE