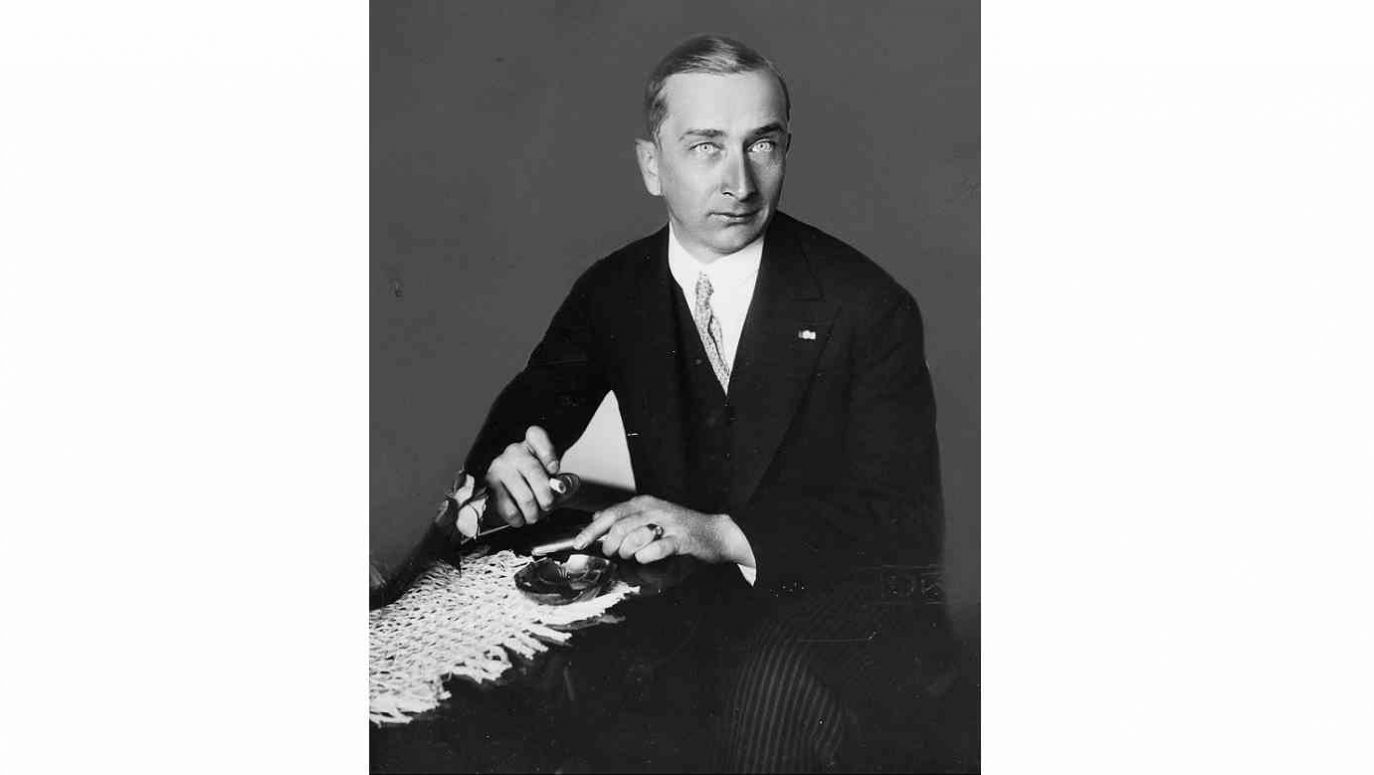

Matusiński entered the Foreign Service in May 1926. He held the post of Deputy Head of the General Consular Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In the years 1933-1935 he was Consul General in Pittsburgh (1933-1935), in 1935 in New York, in 1935-1937 in Lille and from 1937 in Kyiv.

Our diplomats were supposed to leave Moscow for Helsinki. On October 1, 1939, at 2:00 am, Jerzy Matusiński was summoned to the headquarters of the Plenipotentiary of the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the USSR with the Government of the Ukrainian SSR to discuss the transfer to Moscow. Although he had only 350 meters to travel, he drove a car accompanied by two drivers.

The consulate employees waited for them until 6 am and then sent one of the caretakers to check whether the consul’s car was still parked in front of the Plenipotentiary’s office. The Soviets did not allow the caretaker to leave the building, but he saw that the car was missing. At 9.00 the Poles managed to call the police station – they were informed that no one had called Matusiński anywhere.

Ambassador Grzybowski asked the dean of the diplomatic corps Schulenburg and his deputy, the Italian Augusto Rosso, to intervene. At first, deputy commissioner Vladimir Potemkin said he knew nothing about the consul’s fate. In a later conversation with Schulenburg, he announced that Matusiński “is not in our hands”. Therefore, Grzybowski decided to leave the diplomats without explaining the whole matter, and the train to Finland left on October 10.

According to Professor Wojciech Skóra, a historian studying the case, the USSR authorities recognized Matusiński as a spy. After the German aggression against the USSR, one of the Poles released from prison said that he met a kidnapped driver from the Polish consulate who told him that Matusiński had been imprisoned by the NKVD. In 1942, further similar information appeared.

It is known that when the consul arrived at the gate of the office of the Plenipotentiary of the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, six men dressed in civilian clothes got out of the car standing nearby. They searched the Poles and took them to the prison at Korolenko (today Volodymyrska) Street. Then the abductees arrived at a railway station in the suburbs and spent the night in a prison wagon. On October 10, the train reached Moscow, and the Poles were taken to the NKVD detention center in Lubyanka. This was reported by the first driver of the consulate, Andrzej Orszyński, released in 1941, who joined General Anders’ army. The second driver, Józef Łyczek, was also released (both were granted amnesty after the German aggression against the USSR), but he died in unexplained circumstances.

***

The Sikorski-Mayski Agreement of July 30, 1941 restored diplomatic relations between Poland and the USSR. However, it made no mention of the state of war between the two countries. In the additional protocol, the USSR government also guaranteed “amnesty” for Polish citizens: political prisoners and exiles deprived of their liberty in prisons and labour camps in the USSR, as well as prisoners of war. But since it spoke of an “amnesty” for POWs (which was a strange phrase in itself), it recognised that state anyway.

On July 17, 1942, the Chief of the Polish Military Courts, Stanisław Szurlej, decided in a special circular that starting from July 30, 1941, the USSR should not be treated as an enemy - so until the conclusion of the Sikorski-Mayski agreement, that country was considered an enemy.

The activities of the Polish Embassy in the building at Spiridonovka Street were reactivated. However, after the diplomatic corps had been moved to Kuibyshev, the Polish mission was also transferred there. But its activity did not last long. After the discovery of the Katyń massacre in April 1943, the Soviets broke off diplomatic relations with Poland and closed the embassy on April 25, 1943, and its staff left Kuibyshev on May 5 of that year.

The Polish Embassy returned to Spiridonovka Stret in 1945 (albeit with the address Balshoy Patriarashiy Pyeryeulok, temporarily renamed after Adam Mickiewicz). But it represented a very different Polish authority – one completely subservient to Moscow.

– Piotr Kościński

TVP WEEKLY. Editorial team and jornalists

– Translated by Dominik Szczęsny-Kostanecki

When writing the text, the author used, among others:

- monograph „Porwanie kierownika polskiej placówki konsularnej w Kijowie Jerzego Matusińskiego przez władze radzieckie w 1939” included in the book “Polska dyplomacja na Wschodzie w XX – początkach XXI wieku”, H. Stroński & G. Seroczyński (Eds.), Olsztyn-Kharkiv 2010;

- monograph „Jak we wrześniu 1939 roku bolszewicy porwali polskiego konsula” by Ihor Melnikau (Nowa Europa Wschodnia, March 10, 2023);

- book by prof. Jerzy Łojek „Agresja 17 września 1939” (many editions, the first as a samizdat publication in the Polish People’s Republic);

- book by Marek Kornat and Mariusz Wołos „Józef Beck” (Warsaw 2021);

- his own novel „Wrzesień ambasadora” (Warsaw 2022).

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Meanwhile, already on September 11, the Soviet Ambassador Nikolai Sharonov left Kremenets, where the Foreign Ministry and all diplomatic missions had taken shelter. It was described in the account of US Ambassador Anthony Drexel Biddle Jr. His encounter with a Brazilian diplomat in the streets of Kremenets was reconstructed in the novel “Wrzesień Ambasadora [“Ambassador’s September”] as follows:

Meanwhile, already on September 11, the Soviet Ambassador Nikolai Sharonov left Kremenets, where the Foreign Ministry and all diplomatic missions had taken shelter. It was described in the account of US Ambassador Anthony Drexel Biddle Jr. His encounter with a Brazilian diplomat in the streets of Kremenets was reconstructed in the novel “Wrzesień Ambasadora [“Ambassador’s September”] as follows: