Many interlocutors say the summer “has passed them by”, they haven’t gone anywhere but they intend to do so after the victory – to Crimea.

see more

Well, that's right, because as a historian you have quite a “tasty” research interest.

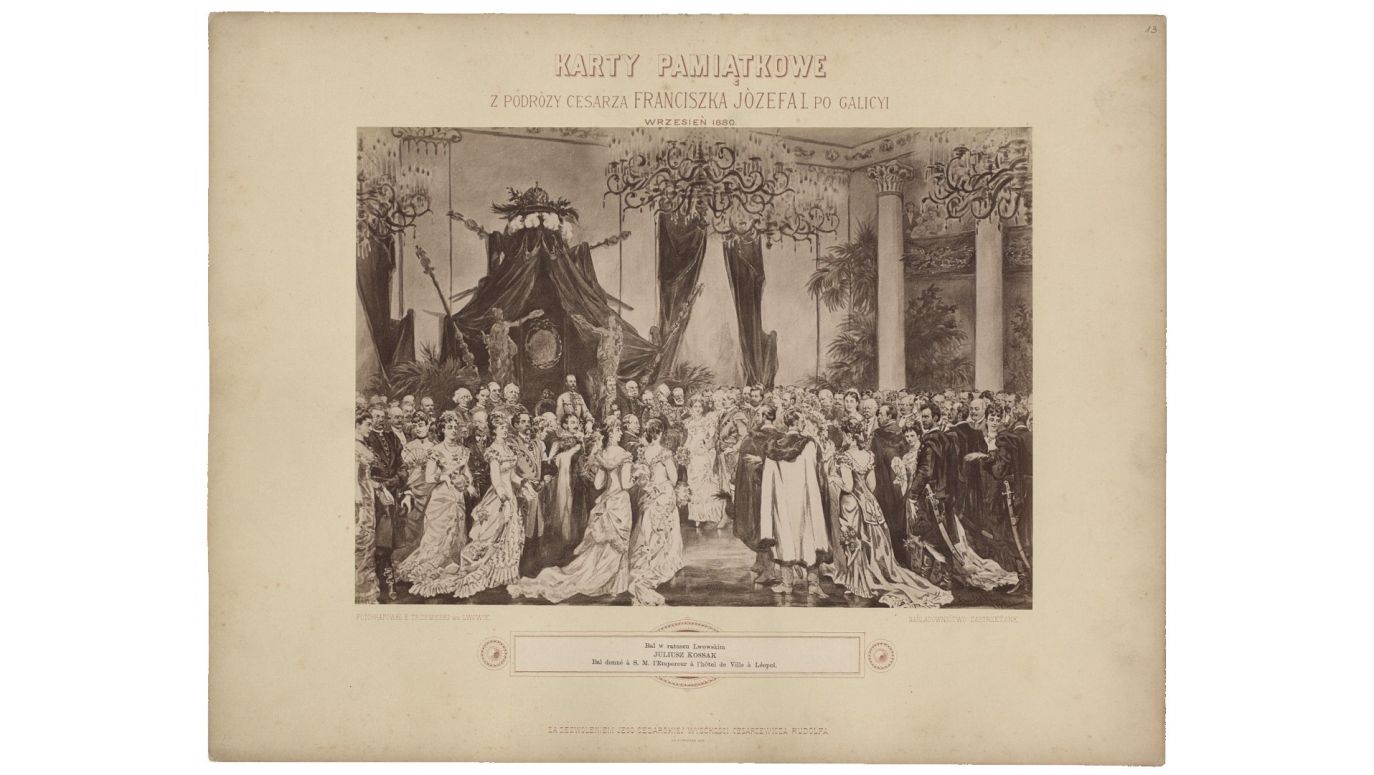

For years I have been studying Galician cuisine and the culture of the Polish-Ukrainian borderland. I have written several books about it, and a book by my colleague Marianna Dushar "Lviv cuisine" is being published in Poland. My contribution was to outline the historical background. The book tells the story of Lviv cuisine in a completely new way, not only through the prism of memories and nostalgia of people from the border area, but describes the phenomenon of Lviv cuisine in a solid way. Moreover, and this is the interesting thing, a prediction is made about the direction in which this cuisine is currently developing.

It is developing so much that the name of the basic dish has been changed.. …

„Ruskie pierogi” (Russian dumplings)?

Well, yes, you can't actually buy them here anymore. The Poles themselves have started to change the names on the labels.

I strongly oppose this! And I would like to say that Russian dumplings are just fine, and one day will be included in the list of intangible cultural heritage UNESCO under this very name. I appreciate very much that Poles kept silent about this decision, because it is necessary to say quite frankly that this dish is a common heritage of both nations, one of which invaded the other. But still the word 'Ruthenian' does not mean 'Soviet' or 'Russian'.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE  Probably, but I am unable to erase this connection from my subconscious. I associate 'Ruski' with one thing and it is by no means a positive term.

Probably, but I am unable to erase this connection from my subconscious. I associate 'Ruski' with one thing and it is by no means a positive term.

Well, that's true, and the term derives not from "Russky" as people in the Soviet Union were called in Poland, but from Kievan Rus itself. And Kievan Ruthenia is, after all, the old name for the present Ukrainian state. The Ukrainian state came into being only in the 16th century and after 1721 it adopted the name of the Russian Empire for itself. If this were not the case, the terms 'Ruthenia', 'Rus' and 'Ruthenian' would not have such associations as the designation of certain things as Ruthenian during the communist era. If we look at it from the perspective of bores like me, from the perspective of an academic chair, I would leave that name alone. On the other hand, there is no reason to crumble the copy, if someone really wants to, let him call these dumplings 'Ukrainian', although it would be fair to call them 'Ukrainian-Ruthenian dumplings'.br>

These very dumplings were the hallmark of Lviv cuisine?

This is more the case with the Lviv kiszka, but also with the tripe, which is completely different from the Mazovian. For there is an interesting aspect of Lviv cuisine: it was closer to the Black Sea and the Mediterranean than to the cold Baltic Sea. Many Armenians, Greeks and Jews lived here, which had a great influence on the spices and taste of Lviv dishes. From the culinary point of view, Lviv is a very special city. In Polish there are even songs about our regional cuisine: "Chlib kulikowski" by Marian Hemar, a beautiful song, "Ballad about Miss Franciszka" and Lviv kishka, and some other similar things. Before the war there was even a song about Lviv coffee. What else is there to say, after all, Baczewski's vodka is a product Made in Lviv!

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE