Almost everything here is authentic, the texts of reports and denunciations, sometimes quoted in extenso, such as Bolko's fatal letter to the Security Office in June 1949. Almost all the characters are real, from the torturers dealing with Bolko to his colleagues. For the sake of a bit of fiction in the personal plot, I changed my protagonist's name. In the play, he is Bolko Chmielarz.

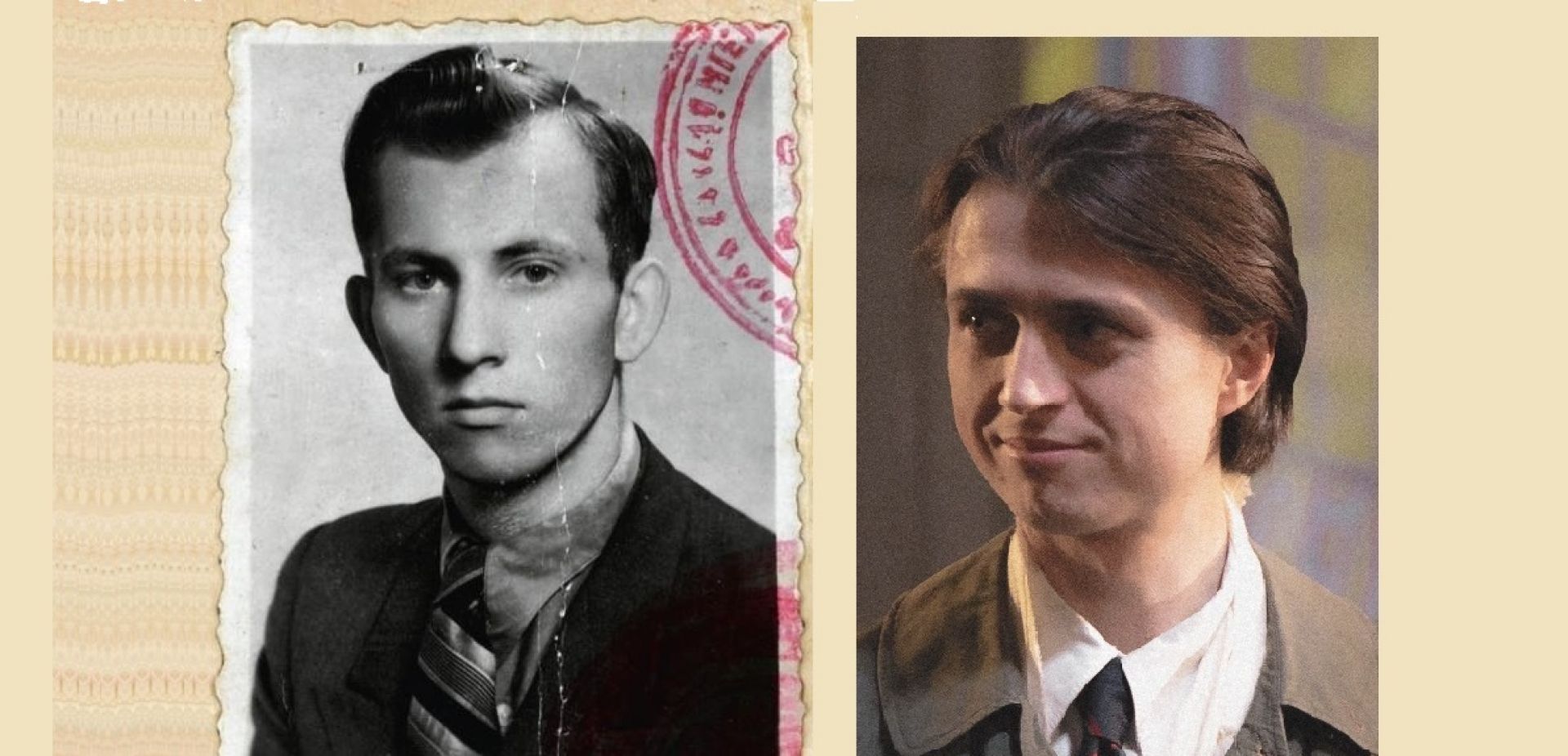

From the papers collected in Bolek's Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) dossier, suffering emanated. From his own testimony and from the secret police reports about him. I asked myself a question: how was it possible that this boy, a soldier of the Zoska Battalion during the war, who lost his brother in the Warsaw Uprising and then, caught in a round-up, was sent to a German camp, did not live to receive all possible awards after the war.

Why was he instead beaten, carried away, and finally quite trampled into the ground and broken? That was the logic of Polish history. I decided to commemorate him. Together with his breakdown and actually his fall.

Stalin's Poland resembled no other era in our history, not even, I repeat, the German occupation, where there was terrible terror, but there was nevertheless hope for a change in the wartime situation. After 1945, this hope was finally taken away from the Poles, which is why I do not subject my protagonist to easy judgments. But, without summarising the plot, I also wrote about the rebirth of Bolek, about his getting back on his feet.

Jan Olszewski and his colleagues

My snooping in the IPN archives was supplemented by my conversations with Jan Olszewski, in the last period of his life, when he was already recovering from a stroke. A lawyer and politician, he was already a member of the Grey Ranks in Praga during the war. After the war, he treated his activity in the PSL youth group as a natural consequence of those wartime choices.

Born in 1930, he was 17 in the year of the rigged elections. He was active in the structures commanded by Bolek. He remembered perfectly the atmosphere, but also the drama of the fundamental events.

Did you know one fact? It was 26 October 1947, a Sunday. Mikolajczyk had disappeared, fled abroad. Colonel Franciszek Kamiński, former commander of the Peasant Battalions and PSL MP, asked a group of boys, high school students from the aforementioned PSL youth group, to guard the party's building in Aleje Jerozolimskie amid the political turmoil.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

They came there to a reading of PSL activists. But they treated it as a war task. They didn't let in the PSL-Left splitters trying to take over the building and the party. But they naturally succumbed to the secret agents who beat them severely.

For me it was another Polish Thermopylae. They were expelled from schools. A few of them went after that in March 1948 to join the forest partisans, with a national tinge, by the way. One of those who made this choice was Józek Lukaszewicz, a boy from the village. His parents sent him to school in Warsaw, as he came from the Plock area incorporated into the Reich during the war. He became a colleague, indeed a school friend, of Janek Olszewski, and sat with him in the same bench.

Olszewski urged them not to go to the forest. A classic situation from Polish history, one of the many dilemmas over which attitude to choose. After three months, the unit was broken up. Józek and several of his colleagues were sentenced to death.

Jan Olszewski had a lifelong dialogue with his late friend. And he asked himself what would have happened if, on that fateful October day, he himself had ended up in the PSL building. What choice would he have made then. And so, saved by chance, he was admitted to law school in 1949.

Praga also fought against communism

How could it not be told? About Bolek, the Rejtan of Praga, albeit with a blemish, with a breakdown to his credit. And about the boys who put up a hopeless fight, although they initially chose civil resistance, in theory somewhat safer. They were all children of the workers of Praga, sons of bakers, chauffeurs. Bolek is the son of a railwayman, as is Janek Olszewski, who is also one of the protagonists of my play - under his own name.

They were shaped by their schools (including those during the war, when certain subjects were taught illegally), and the scouting movement was very important. It was through them that the workers' son Bolek and his two brothers became friends with boys from the intelligentsia and ended up together in the Zoska Battalion. In some cases, families were also influential. Janek Olszewski was the cousin grandson of the executed Polish Socialist Party (PPS) fighter of 1905, Stefan Okrzei. Bolek's father was also a member of the PPS.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

They came there to a reading of PSL activists. But they treated it as a war task. They didn't let in the PSL-Left splitters trying to take over the building and the party. But they naturally succumbed to the secret agents who beat them severely.

They came there to a reading of PSL activists. But they treated it as a war task. They didn't let in the PSL-Left splitters trying to take over the building and the party. But they naturally succumbed to the secret agents who beat them severely.