Kazimierz Barcikowski was probably the only member of the council who had a specific task to fulfill, assigned by Jaruzelski – to go to Primate [of the Catholic Church in Poland] Józef Glemp and inform him about martial law. The others returned home in police cars. Along the way, they must have seen soldiers, armored personnel carriers, and police columns. The army and the police actually started their operations well before the Council of State had passed anything – certainly before midnight.

Most of the members of the council remained in their positions until the end of the term, so until November 1985. Reiff was dismissed from his position already in 1982, in the same year, Professor Szczepański left the council. Krystyna Marszałek-Młyńczyk was dismissed a year later. And essentially, this was their punishment for their behavior on the night of December 13, 1981.

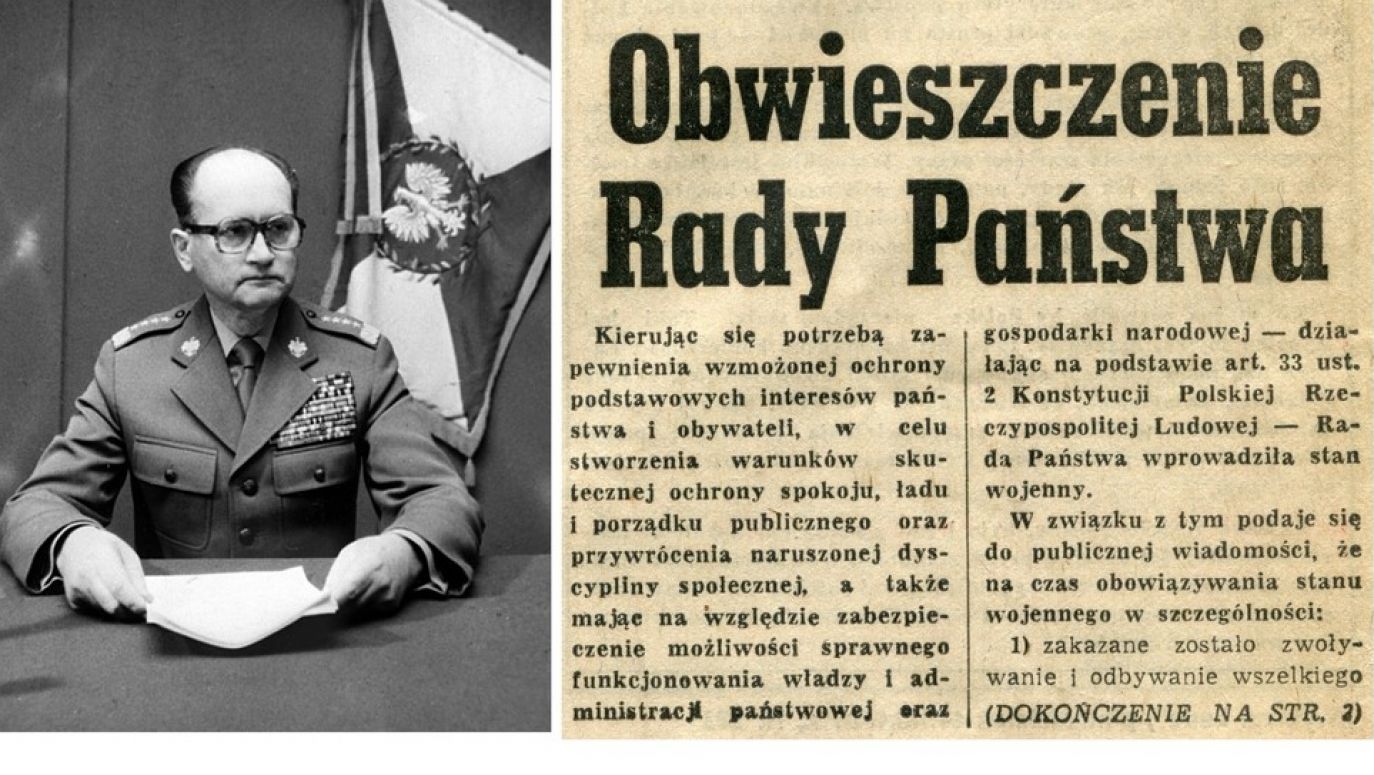

After 1989, attempts were made to bring members of the Council of State who voted for the decrees on martial law before the State Tribunal. The fact was indisputable: the council violated the Constitution of Communist Poland – it could only pass decrees outside sessions of the Sejm, and such a session had been in progress. Ultimately, however, this did not happen. On the other hand, in 2011, the Constitutional Tribunal found the decrees adopted on December 13, 1981, to be illegal, contrary to both the Constitution of Communist Poland and the International Covenant on Personal and Political Rights of 1966.

Why did the meeting look like it did – generally bland, without much discussion, basically approving what Jaruzelski and his associates had decided? First of all, because since the establishment of the Council of State in 1952, it had been the body masquerading as the state authority. In fact, this power was located elsewhere – it was in the Politburo of the KC PZPR.

In addition, in the case of the council adopting martial law, the selection of its members (conducted by the newly elected Sejm) took place in April 1980, so a few months before that August. And then a lot changed, including the leadership of the PZPR and both “allied parties”. Despite this, very few changes took place in the council – in December 1980, the former First Secretary of the KC PZPR, Edward Gierek, and a little earlier, the former Secretary of the Central Committee, Zdzisław Żandarowski, departed. Those who remained, apart from Barcikowski, who was selected to the council at the end of 1980, knew perfectly well that they would no longer participate in making any key decisions. These were made completely without their input.

Although in fact at 1 am on December 13, 1981, they had enormous power, and they used it – in the way that Wojciech Jaruzelski and his people wanted – because of how this institution was constructed, it was never meant to have even a sliver of independence.

– Piotr Kościński

TVP WEEKLY. Editorial team and journalists

–Translated by Nicholas Siekierski

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE