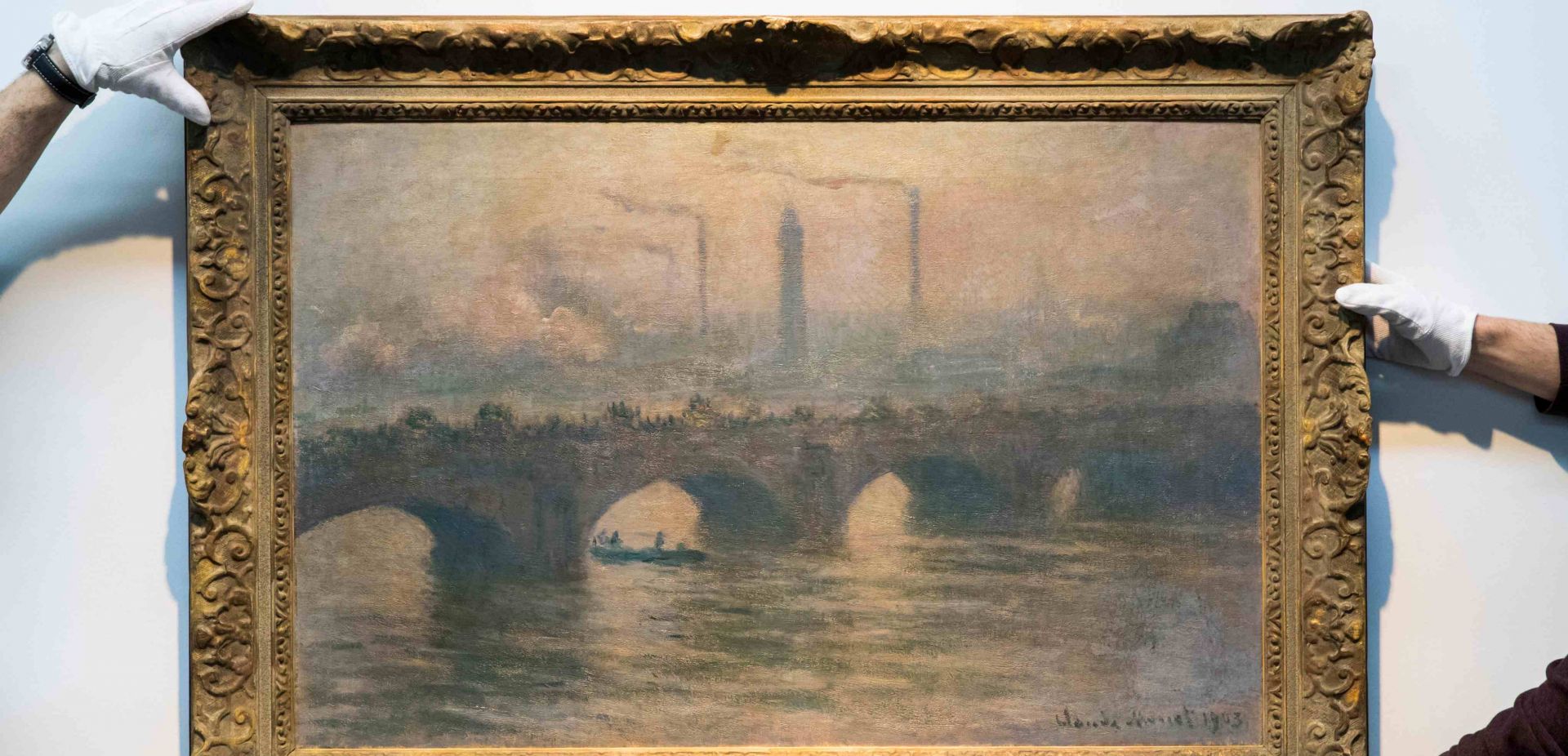

Investigators found that the 1984 Lausanne exhibition that gave rise to the search was called “L'impressionnisme dans les collections romandes” and was held at the “Fondation de l'Hermitage”. In addition to Pissaro’s painting, works by Corot, Monet, Renoir and Sisley, also belonging to Lohse, were exhibited there. The officers also found documents showing that in 2006 the German art historian was auctioning three paintings from his collection at the Fischer Gallery in Lucerne.

Suspicious transactions in Lempertz

The Lempertz Auction House in Cologne began its suspicious activities before the war and before the Holocaust. In 1937, it auctioned 228 objects belonging to Max Stern, an art dealer with Jewish roots, whose gallery was closed by the decision of the Chamber of Fine Arts of the Third Reich, under a law on which another hero of this story, Weinmüller, collaborated. The auction still raises a lot of controversy and some researchers see it as a “forced sale”. But there are also many indications that Max Stern could still be its silent participant.

In 1939, the same auction house sold the collection of the Jewish collector Walter Westfeld, arrested by the Nazis. Works by Peter Paul Rubens, Camille Pissarro, Carl Spiztweg, among others, were put up for auction.

In 1942, Westfald was deported to the Terezin concentration camp, and a year later he was transferred to Auschwitz, where he died. The date of the collector’s death is unknown. He was pronounced dead in 1945, after the camp was liberated.

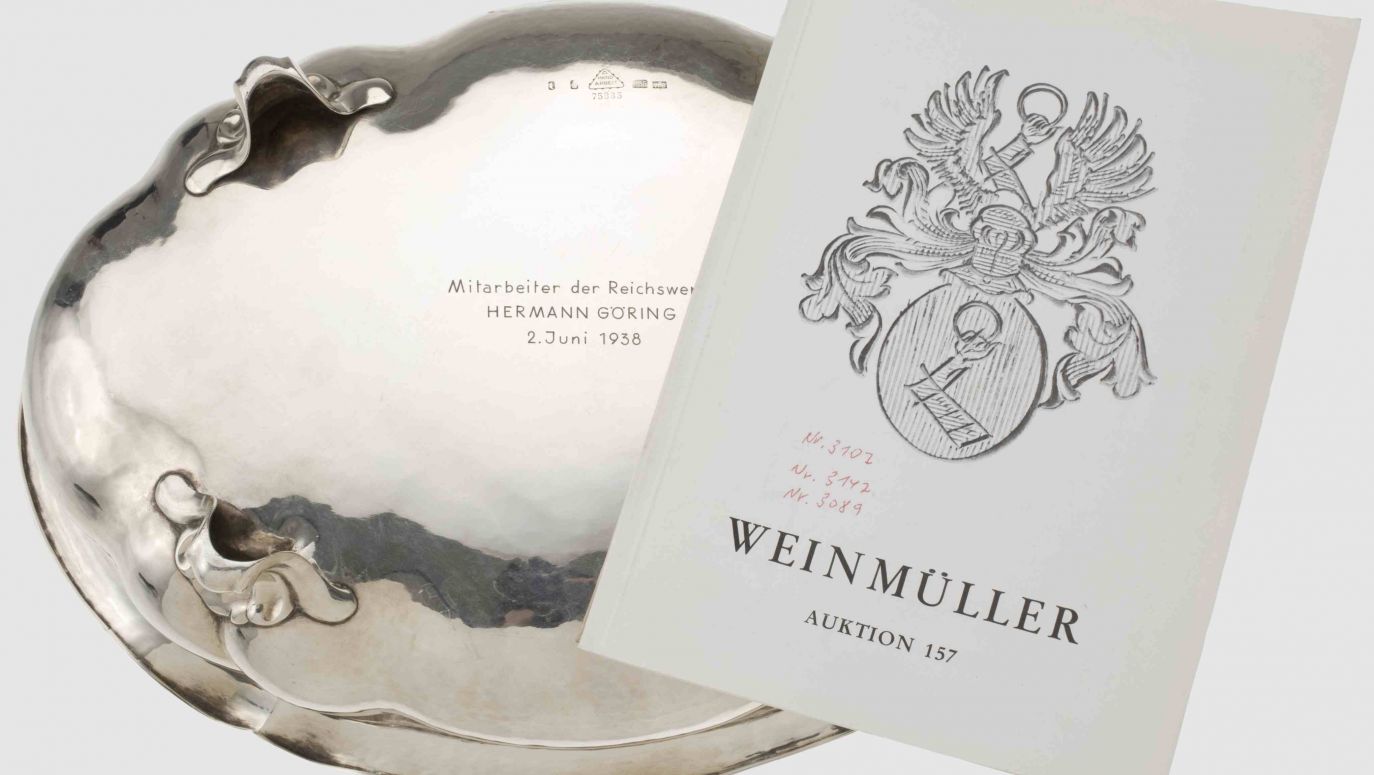

In the mid-1960s, Lempertz, together with the auction houses of Leo Spik in Berlin and Weinmüller in Munich, brokered – presumably unwittingly – the sale of 113 inferior works from Herman Göring’s collection. These artifacts were put up for sale by Halldor Soehner, director general of the Bavarian State Picture Collection, who concealed their origin.

In May 1981, 20 to 30 paintings belonging to Albert Speer were sold at an auction. He was also a high-ranking Nazi politician and minister. Due to his education and connections, he was called “Hitler’s architect”. And it was his art collection that was sold under the label “private collection”. In this case, there could be no question of the unconscious involvement of the auction house. The owner’s name has been concealed on purpose.

***

Such stories, revealed from time to time, cause shock, but also provoke questions about the art trade in Europe. Do we already know everything about the post-war activities of Nazi art dealers? Do we really know the fate of minor work from collections looted by dignitaries of the Third Reich? How is the process of recovering the assets of the heirs of the pre-war owners progressing? How many paintings of suspicious provenance could have passed through renowned auction houses? After WWII, most of them did not bear any responsibility for their actions, and some prospered, continuing to trade in stolen artifacts.

– Małgorzata Borkowska

– Translated by Dominik Szczęsny-Kostanecki

TVP WEEKLY. Editorial team and jornalists

Bibliography:

“Kunsthandel im Nationalsozialismus: Adolf Weinmüller in München und Wien” – Meike Hopp

“Die Bilder sind unter uns. Das Geschäft mit NS-Raubkunst” – Stefan Koldenhoff

“Art Dealers Network in the Third Reich and The Post War” by Jonathan Petropoulus. “The journal of contemporary history” Vol 52 No. 3.

https://claremontca.blogspot.com/2009/06/dept-of-found-art.html

„Grabieżcy kultury i fałszerze sztuki” – Jan Świeczyński. „Wydawnictwa Radia i Telewizji. Warszawa 1986”. str 122

„Sprawa Adolfa Weinmüllera. Nowy skandal ze zrabowaną sztuką?” – Andrzej Pawlak. Deutsche Welle, 03.06.2014

„Looted Paintings Found in Nazi Dealer Safe” – „Der Spiegel” 06.06.2007

„Latami handlował skradzionymi po wojnie obrazami. Gdy zmarł, dzieła Picassa czy Moneta znaleziono w tajnej skrytce” – Anna Arno, „Wysokie Obcasy”, 06.10. 2021

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

He is also worth mentioning by the way, because in the Nazi system of power it was not just anyone. During the war, Mühlmann in the rank of SS-Standartenführer was secretary of state and head of the Main Department of Science and Education of the Government of the General Government, but also the head of an organization called “Dienststelle Mühlmann” (“Mühlmann’s office”). He is responsible for looting and transporting works of art from occupied Poland.

He is also worth mentioning by the way, because in the Nazi system of power it was not just anyone. During the war, Mühlmann in the rank of SS-Standartenführer was secretary of state and head of the Main Department of Science and Education of the Government of the General Government, but also the head of an organization called “Dienststelle Mühlmann” (“Mühlmann’s office”). He is responsible for looting and transporting works of art from occupied Poland.