In Armenian circles, Monika is called not only the

spiritus movens, but also the workhorse of meaningful action. In recent years, she has become so engrossed in Armenian affairs – mainly archives, old documents, maps, estate and metric records, court papers – that she has almost immersed herself in this non-existent world. And she has written two very interesting books

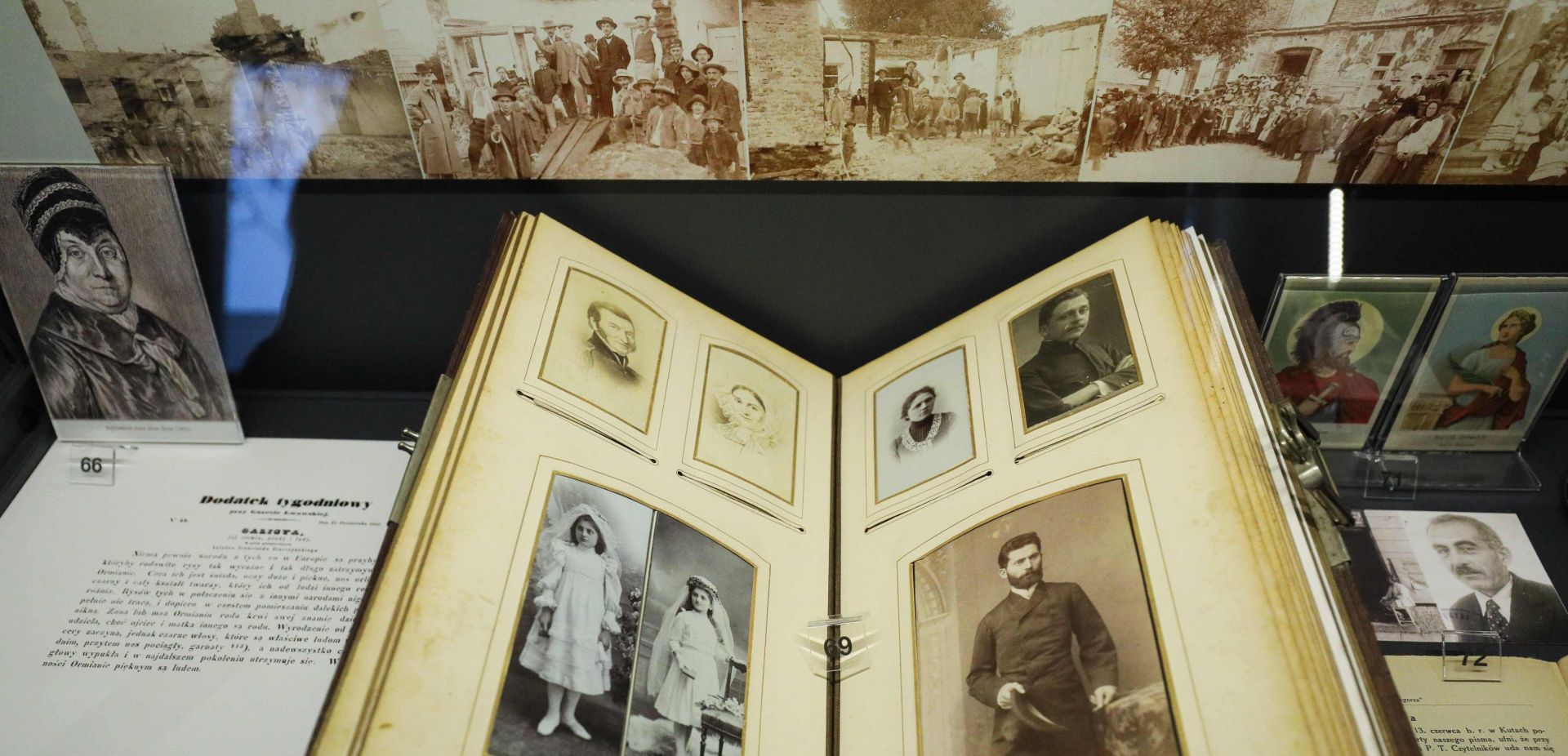

(we printed excerpts from one of them in our pages a few weeks ago),, although the ongoing tasks were endless. First and foremost, to ensure that the Foundation of Culture and Heritage of Polish Armenians (FKiDOP) had somewhere to go and somewhere to show its treasures.

Expatriation over the Vistula

Armenians have been in Poland for centuries. They received their first privilege in Lwów from King Casimir the Great in 1367, and it was confirmed by Władysław Jagiełło in 1388 in Łuck. But it was not until the post-war loss of the Borderlands – with its mythical Pokucie, Lwów cathedral and apricot orchards on the Čeremosh River – that Polish Armenians flocked to the Vistula and Odra. En masse. They refer to that exodus as “expatriation”, in order to dissociate themselves once and for all from the ghastly communist “repatriation”, because no one was returning to their homeland, but being deprived of it.

Borderlanders – including Polish Armenians – were leaving, some on the last possible transport, with their holy paintings, parish books, great-grandparents’ travelling trunks and other trinkets, which in the new place of settlement no longer fulfilled their role. And slowly they became just mementos of history that could not be shown for years anyway.

– Father Kazimierz Filipiak, the last pastor of the Armenian-Catholic parish in Stanisławów, wandered around Poland for several years with parish suitcases and boxes – says Monika Agopsowicz, whom this legendary priest baptised in Gdańsk, because it was there that he finally settled in 1958. He took over the church of St Peter and St Paul, ruined by Soviet soldiers and then devastated for years, which slowly became a landmark for the dispersed Armenian community.

Monika Agopsowicz writes about this in her book “Kresowe Pokucie. Rzeczpospolita Ormiańska” [Pokucie in Eastern Borderlands. The Armenian Republic], quoting the priest: “In the last weeks before the deportation I was very often summoned to the NKVD, sometimes even twice a day, and I had their visits at my rectory every hour. They were concerned above all with the Miraculous Image of Our Lady of Grace, which I was not allowed to take with me. So I had to take the Miraculous Picture out of the altar secretly – thanks to the kindness and helpfulness of two poor old people who agreed to take the Miraculous Picture, it travelled to the West.”

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE