TVP WEEKLY: Let's perhaps start with a question related to historical fiction, but one that is important for Ukraine and uncomfortable for Russia. Polish actor Marcin Dorocinski plays Jaroslav the First in the popular series about the Vikings. Is he a figure as important to your history as Mieszko the First is to us?

SERHII PLOKHY: Jaroslav the Wise (born c. 978 , died 1054 - editor's note), apart from being described in the Scandinavian sagas, was actually a particularly important figure for our history. He drafted the first laws and codified the common laws, and introduced the first system of its kind in the entire region of eastern Europe. Thanks to him, the first cathedral and the first library in this part of the continent were built. Not only that, but his daughters went on to marry the rulers of Europe's greatest dynasties. Elisabeth became the wife of the famous Norwegian King Harald III the Harsh, Anastasia of Andrew I, King of Hungary, Anna of Henry, King of the Franks. Our ruler's sister was the wife of the Polish King Casimir the Restorer, and his son Zaslav in turn married his sister and the daughter of Mieszko II, Gerturda. So yes, you are right that Jaroslav the Wise is one of the most important figures in Ukrainian history, which is why his image appears on our banknotes. And I guess that's why this story carries such an inconvenient truth for the Russians, because Iaroslav created Kievan Ruthenia, not the Muscovite state. Meanwhile, disregarding the facts, Vladimir Putin continues to claim that Muscovite Ruthenia and Kievan Ruthenia are the same state and we are the same nation, It is quite like someone in the USA today saying that London should belong to the United States because the kings of England once colonised North America.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Is this by any chance a Soviet point of view? You went to school back in the USSR. What view of history were you taught? What facts and names were forbidden?

Is this by any chance a Soviet point of view? You went to school back in the USSR. What view of history were you taught? What facts and names were forbidden?

The history of Kievan Rus' was not forbidden, but it was plugged into the whole concept of Old Rus' as the beginning of Russian nationhood. For the real roots of the Soviet Union, according to school textbooks, were even further back, in the ancient kingdom of Urartu in Asia Minor (present-day Armenia - ed. note). This was to be the true cradle of nations united under Soviet rule. The first chapter of every history book began with Urartu. But if you ask about forbidden names, it was not that some were passed over in silence, only that their importance was deliberately diminished, mainly because of the theory of class struggle.

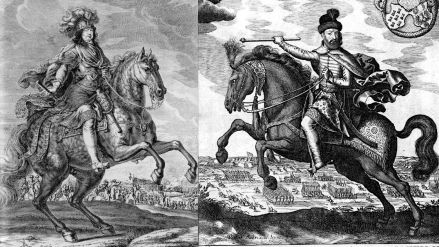

One such figure was, for example, Konstantin Ostrogski (the first Great Lithuanian Hetman of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth - editor's note), Prince of Volhynia, the true godfather of the Cossacks in the 15th century and founder of one of the most powerful families, which after the Union of Lublin in 1569 further increased its wealth and possessions. Another leader inconvenient for the historiography of the USSR was Ivan Mazepa (1639-1709; Hetman of the Zaporozhian Army and Left Bank Ukraine in 1687-1709 - editor's note), treated as a symbol of the betrayal of Rus. Bohdan Khmelnitsky, on the other hand, was presented as the one who first sought to annex Ukraine to Russia. The figure of Mykhailo Hrushevsky, the most important 19th century Ukrainian historian, on the other hand, was the epitome of nationalism. Semen Petlura had the image not of a socialist, but of a nationalist and anti-Semite, and Stepan Bandera was a fascist. The latter, moreover, was completely erased from history and identified unequivocally negatively.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Is this by any chance a Soviet point of view? You went to school back in the USSR. What view of history were you taught? What facts and names were forbidden?

Is this by any chance a Soviet point of view? You went to school back in the USSR. What view of history were you taught? What facts and names were forbidden?