But who reads poetry today? A picture speaks with the power of a thousand words, books and articles need illustrations, an anchor for helpless words. How to fit hunger cramps, diarrhea and agony into kitschy “Ukrainian” scenography, which is suggested to us by our lazy imagination (black-browed women in white scarves, sunflower fields, suburban street flooded with summer sun, clay jugs on the fence rails)?

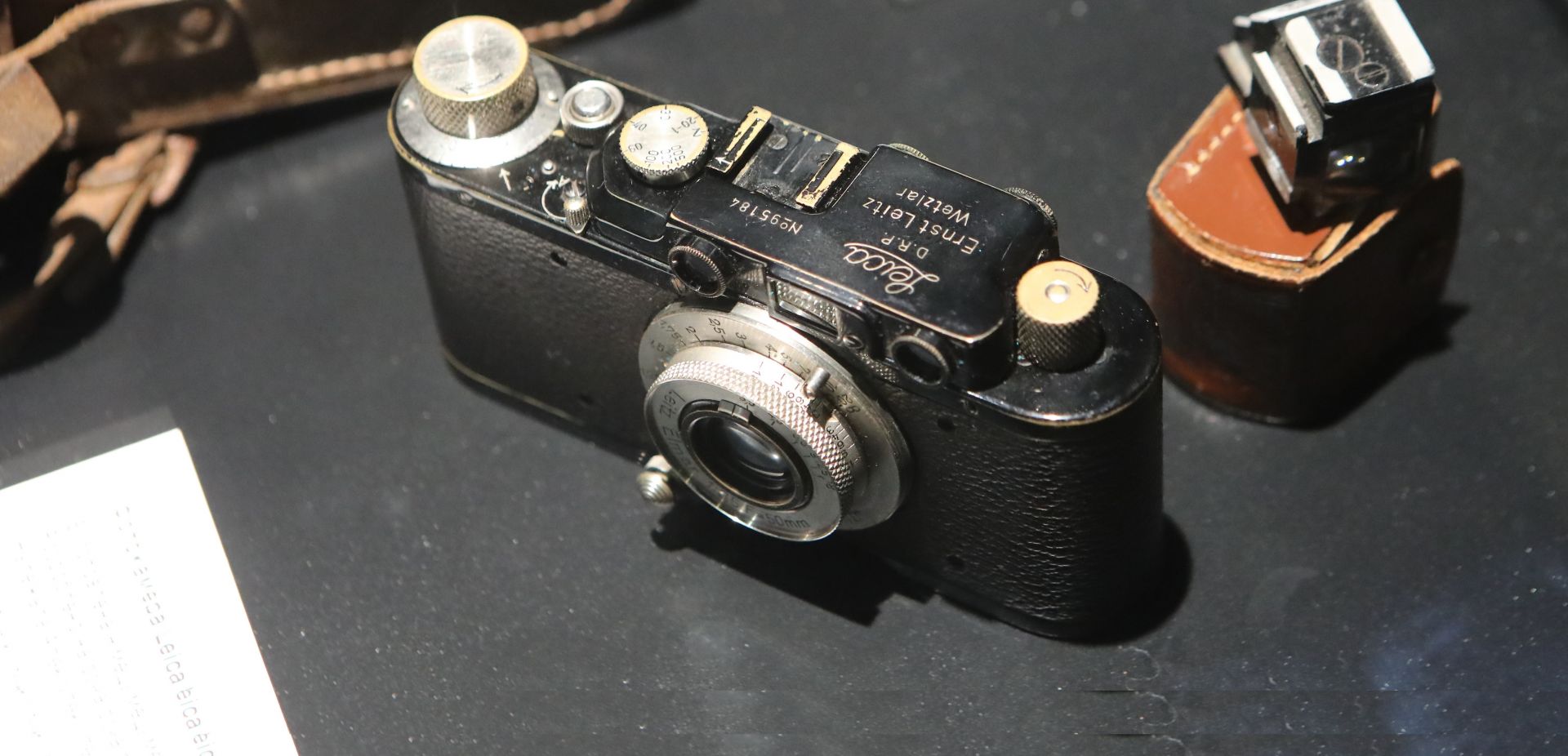

And this is where Wienerberger comes in with his Leica.

SS photojournalists

He wasn't the first. The theme "Photography and Genocide" is a subject of books and seminars, far from closed. It is possible that Armin T. Wegner stands foremost among the group of photographers to focus on a nation being liquidated. Wegner was a military doctor, who was assigned to the German Medical Corps supporting the Ottoman Sixth Army’s activitiees in Syria and Mesopotamia. In 1915 Wegner photographed the "death trails" along which the Armenians wandered towards their destruction. Transferred under pressure from the Turkish authorities to Europe, he managed to smuggle negatives in his uniform belt. They have given us an idea of Mec Jeghern, the first genocide of the twentieth century.

Of course, the most extensively photographed was the Holocaust. It was unabashedly documented by officers from the Politische Abteilung Erkennungsdienst (probably the most widely known is a photo of a boy in a short coat, aimed at by SS-Rottenführer Josef Blösche). Others were taken by Polish prisoners in Auschwitz: Wilhelm Brasse, a photographer from Żywiec, and Mendel Grossman, who had been locked in the Łódź ghetto. But the Holodomor? Where did the equipment, film, determination, and the cloak of invisibility come from?

Alexander Wienerberger's biography , at least in the first years of his life, follows Central European biographical 'matrices'. Born in 1891 to a wealthy Viennese family, nominally Czech-Jewish, he considered himself Austrian. A proud student of the Faculty of Philosophy, he went as a one-year volunteer to the Carpathian front and was taken prisoner by the Russians in 1915.

VISIT AND LIKE US

VISIT AND LIKE US

Like many Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war, he had no particular attachment to the declining monarchy, but he was impressed by the momentum and ideals of the two revolutions he experienced in Russia in 1917, the first of which already brought him freedom. He did not become a communist fellow-traveler like the carefree globetrotter, the Czech writer Jaroslav Hašek , nor a communist official and politician like the Hungarians Béla Kunand and Mátyás Rákosi. However, he did decide that he could build a life for himself in Moscow, where he settled and married.

A little stabilization à la Russe

He started with a small chemical laboratory, founded with friends in the summer of 1917, in what was to prove to be a fluctuating life style under the war time conditions of communism, and later the Soviet Union’s New Economic Policy (NEP) as proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921. Sometimes relatively prosperous, at other times life was a struggle (in 1919 he tried to escape to Austria and spent three years as a prisoner of Lubyanka). Eventually the Soviet authorities appreciated his engineering talents, despite the fact that he was a self-taught chemist. In the second half of the 1920s, he was in charge of production in a paint and varnish factory, and at the turn of the decade – was made responsible also for the production of explosives!

In 1928, he was granted the rare privilege of being allowed to go to his family in Austria. On his return, he brought his second wife, Lilly Zimmermann, with him, his first marriage having broken up a year earlier. In 1932, he was nominated as the technical director of the plastics factory in Lubuchany [close to Moscow], and in the first months of the following year he was assigned to a similar position in Kharkiv.

We really don't know what made a self-made man, a cheerful bourgeois who had brought a camera from Austria to record the image of his little Margot on a sleigh and a gramophone to dance with Lilly in their five-room apartment, to direct the lens from his daughter's chubby cheeks on the swollen face of an unknown girl. His account in his memoirs published in 1939 ("Hart auf hart. 15 Jahre Ingenieur in Sowjetrussland. Ein Tatsachenbericht") is written in the language of pathos, as if tailored to the tastes of the audience.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Like many Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war, he had no particular attachment to the declining monarchy, but he was impressed by the momentum and ideals of the two revolutions he experienced in Russia in 1917, the first of which already brought him freedom. He did not become a communist fellow-traveler like the carefree globetrotter, the Czech writer Jaroslav Hašek , nor a communist official and politician like the Hungarians Béla Kunand and Mátyás Rákosi. However, he did decide that he could build a life for himself in Moscow, where he settled and married.

Like many Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war, he had no particular attachment to the declining monarchy, but he was impressed by the momentum and ideals of the two revolutions he experienced in Russia in 1917, the first of which already brought him freedom. He did not become a communist fellow-traveler like the carefree globetrotter, the Czech writer Jaroslav Hašek , nor a communist official and politician like the Hungarians Béla Kunand and Mátyás Rákosi. However, he did decide that he could build a life for himself in Moscow, where he settled and married.