Of his other roles, I would single out Jan Mincel from Ryszard Ber's serialised “Lalka” (

The Doll). It wasn't until many years later, watching this film again with my children, that I discovered that Bareja acted in it. In it, he is the true embodiment of vitality, just like his character. The other roles are more like episodes or comic shorts. It's important to note that Bareja mostly acted in movies made by his friends from his student days. As a result, we see him in Jan Lomnicki's "Dom" (

Home) series, Andrzej Munk's "Eroica", as well as Jerzy Hoffman and Edward Skórzewski's "Gangsterzy i filantropi." This was how they helped each other back then. When one of the group didn't have work or was censored – and this happened quite often in those days – they were hired on set to make a small income. I would highlight Henryk Kluba who played an excellent role in Bareja's "Nie ma róży bez ognia" (

A Jungle Book of Regulations). He plays the role of a neighbour called Poganek, planning to organise an orgy.

Bareja also often cast members of his own family to play in his films, with the notable exception of his wife...

This is a consequence of his idea to treat his films like a kind of memoir. The director employed his children and mother in episodes several times. For me, the funniest is [his son] Jan Bareja's episode in "Miś” [

The Teddy Bear] – a boy counting people in line at a drugstore. He is the one who tells Suwala [played by Bronisław Pawlik]: "Sir, I've already counted, there are 126 people in line".

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

His wife, Hanna Kotkowska-Bareja, refused to appear in her husband's films, despite several requests. This is paradoxical, because they met on the set of "Szkice węglem" [

The new soldier] by Antoni Bohdziewicz, where she was an extra. Today, she says she regrets that decision. However, at the time, she thought she was simply unsuitable.

Was Bareja faithful to his actors, or was he always looking for new faces?

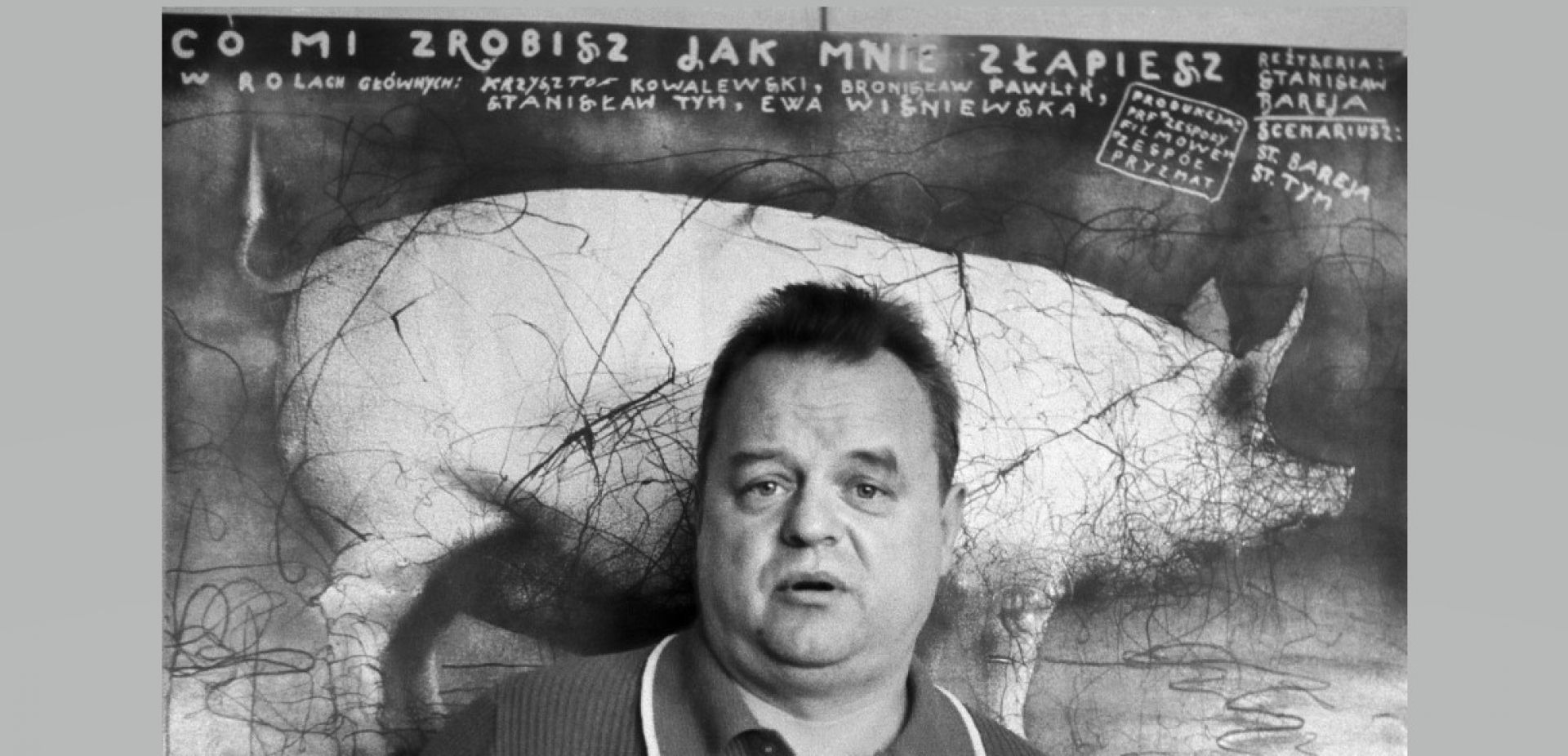

Yes, and no. With Bareja, whom we think of today as a cult director, it was quite different from a young filmmaker out of school. Initially, like any artist, he was looking for his own style and tried his hand at different genres. That's an important word: "genre." Bareja practised “genre cinema” at a time when it was despised in Poland. He filmed a detective story, a comedy, a musical comedy, a typical musical, and the first Polish thriller series, "Kapitan Sowa na tropie". During this time, he chose performers based on the type of films they had played in, but there were some exceptions. Because he employed Bronisław Pawlik from his first feature to the end of his career. And it can certainly be said that he was a "Bareja actor". However, when [Bareja] forged his own character "writing" in the 1970s, around the time of the release of the film "Poszukiwany, poszukiwana" [

Man – Woman Wanted] he chose a group of performers with a similar sense of humour and stuck with them until the end. The most important were his co-writers and actors at the same time, first Jacek Fedorowicz, then Stanisław Tym, but there were many more. For example, Bożena Dykiel, Stanisława Celińska, Halina Kowalska, Janina Traczykówna, Andrzej Fedorowicz, Jerzy Dobrowolski, Wojciech Pokora, Wiesław Golas, Jan Kobuszewski, Mieczysław Czechowicz, Tadeusz Pluciński, Kazimierz Kaczor, Wojciech Siemion, Marian Łącz and Krzysztof Kowalewski.

Did he let his performers improvise?

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE