Tomasz Rowiński, historian and columnist for ‘Christianitas’ quarterly, states the role of Latin in the life of the Church is a source. “The Gospels and Holy scripture to be sure, were not written in Latin, but its Latin translation. This is the Vulgate and to this day serves as the source material, through which we can understand the revelation of God.” He adds “The most important theological texts were written in Latin, from the Creed, to the liturgical texts. Latin also serves as the basis for the reformed material that arose from the Vatican Council. Latin crated and creates the specific theological culture of Christianity.”

Did Saint Peter learn Latin?

Marek Jurek points out that Latin for the Poles had a significant role. Thanks to it, simple people living on the far eastern borderlands, on lands where Latin culture mixed with that of Byzantium, Catholicism with Orthodoxy, they could see themselves as heirs of Roman civilisation. Even if they were unconscious of this fact they participated in it. They now suffer as a result of a commonplace homeliness.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Latin was not the language of the Church from the start of its history. The first was Greek. “But Christ spoke to his disciples in Aramaic. Maybe even the Gospel according to Saint Matthew was first written in Aramaic. But this version has not survived. In the Greek translation there are many Aramaic and Hebrew turns of phrase,”, states Dr Katarzyna Ochman.

She continues that Christ and Pilate probably spoke in Greek to each other. The disciples of Christ after crossing the border of Judea and Galilee, exclusively spoke in Greek “I’m curious if Saint Peter, when he came to Rome leant Latin. He didn’t have, to as Greek was commonly used and known. Latin was the mother tongue of Romans and a literary language. This was the moment when the Church stared to use Latin in the same way as Greek. In the eastern Roman empire, Greek was used, in the western half, Latin,” she adds.

In time. Latin became a lingua franca. Why did it become the language of the Church she wondered? “ Because this was Christ’s will,” she says. “Christ said ‘Go forth and teach all nations’”. She continues “If Christ appeared in Poland today, we would be preaching the Gospel in Polish. But since we have to preach it worldwide we need to use a universal language, and today this means in English.”

She notes that the fall of the Roman empire did not mean the fall of Latin, despite the destruction of state structures which guaranteed this happening and so emerged from the shadows without trouble.

“The barbarians who through generations leading up to the age of Charlemagne, conquered Rome, destroyed its structures but they adopted its language. Charlemagne, who re-ordered western Europe could use his native language, Frankish. But he chose not to do this, since Latin was the literary language. The Church was equally pragmatic. It attempted to carry the word internationally,” Ochman states.

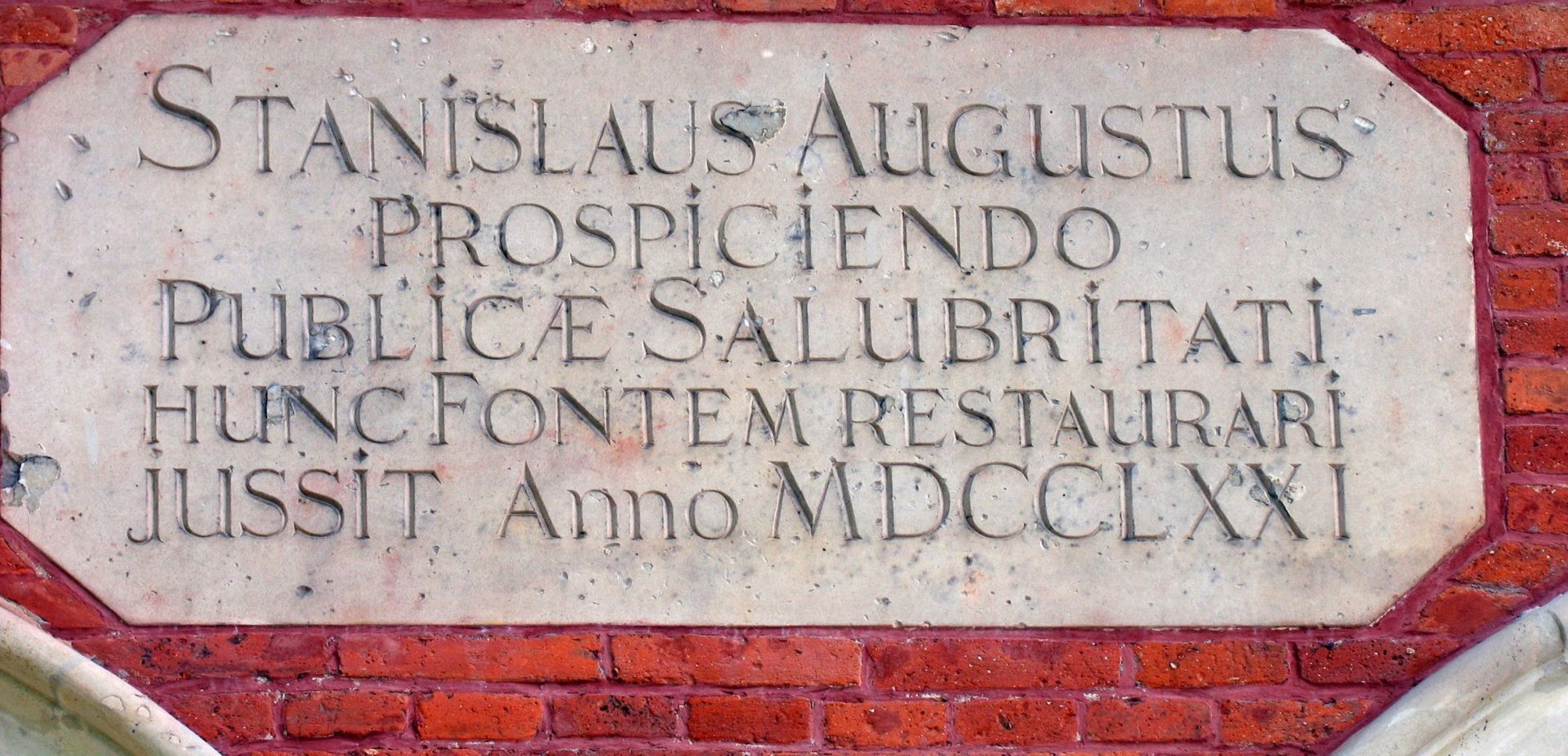

We can take the opinion that Latin lost its significance from the Renaissance. This is a myth. “To the 18th century, Latin was the language of education. Every educated person knew it. Even in the 19th century when it was no longer the academic language of lecturing in schools, the high school pupil knew Latin better, and had more contact with it than a contemporary philology graduate,” she said.

The doctor’s oath

On the wave of 19th century nationalism that shaped nation-states, Latin started to fade. It was pushed into the shadows of national languages. These conditions worsened in the culture of the 1960s and 1970s. There were deep changes in Western civilisation and Latin was pushed out from the liturgy of the Church as a result,” Ochman says.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE