The Nursing Home (DPS) on Widzew Zarzewie is beautifully situated among greenery. Eugenia Pol walked a lot. Always and everywhere alone. Back and forth. With her arms folded behind her back. Upright. Like a soldier. As if standing at attention. She used to have delusions. She would wake up at night. She talked in her sleep. Her roommate could not understand her. Except for one short sentence: "Take this whip" - the story of the guard Eugenia Pol is told by Błażej Torański, author of books about the German camp for Polish children in Łódź.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

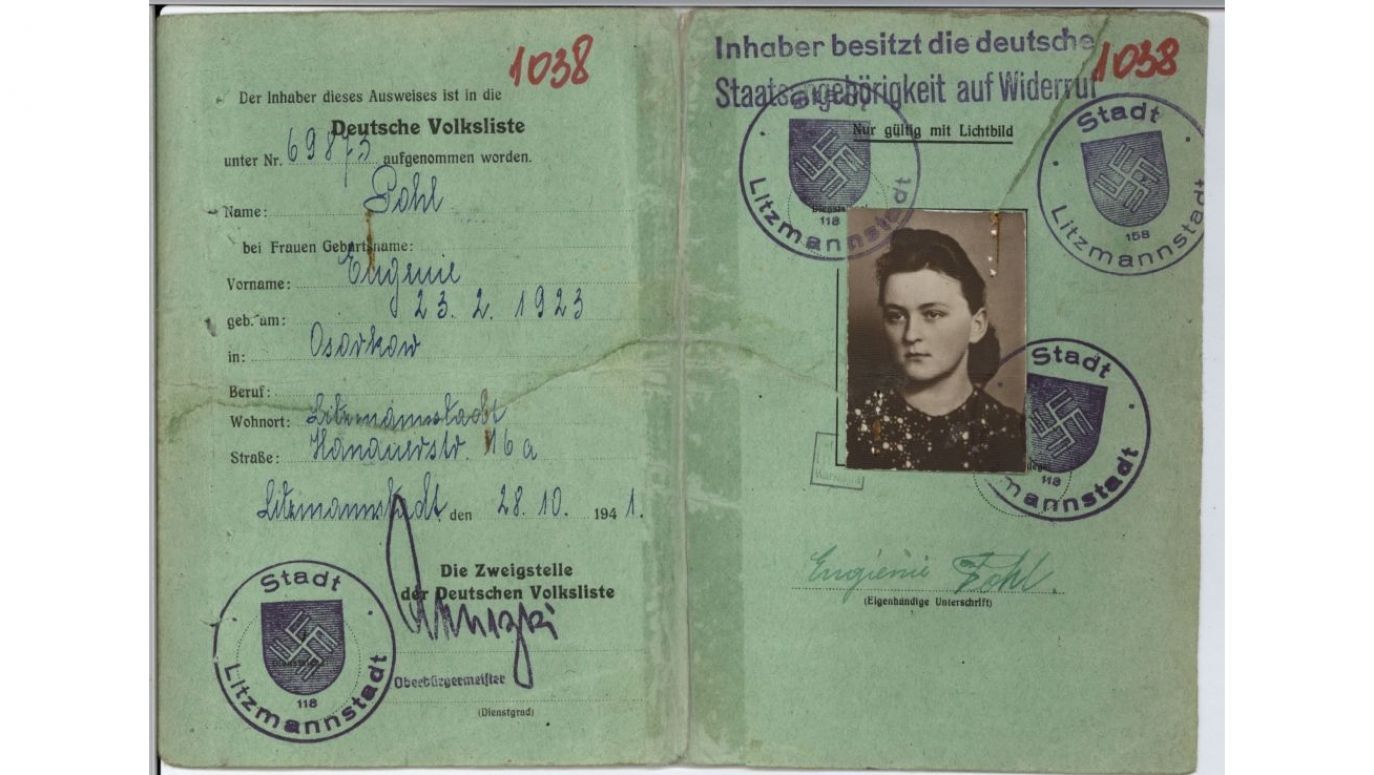

Łódź judge Sabina Krzyżanowska investigated Eugenia Pol between 1945 and 1949, but was unable (or unwilling) to trace her. She received a reply from the Security Office and the Population Register Office that Genowefa "Pohl is not registered in Łódź". Meanwhile, the former guard was permanently living in Łódź at 16 A Chełmońskiego Street, except that she had reverted to the Polish spelling of her surname Pol. This was a clever trick on her part. An effective masquerade.

Łódź judge Sabina Krzyżanowska investigated Eugenia Pol between 1945 and 1949, but was unable (or unwilling) to trace her. She received a reply from the Security Office and the Population Register Office that Genowefa "Pohl is not registered in Łódź". Meanwhile, the former guard was permanently living in Łódź at 16 A Chełmońskiego Street, except that she had reverted to the Polish spelling of her surname Pol. This was a clever trick on her part. An effective masquerade.

How did the Germans tolerate him in the mayor's office?

see more

“I thought I had one hundred divisions behind me but I had a piece of shit” – he said.

see more