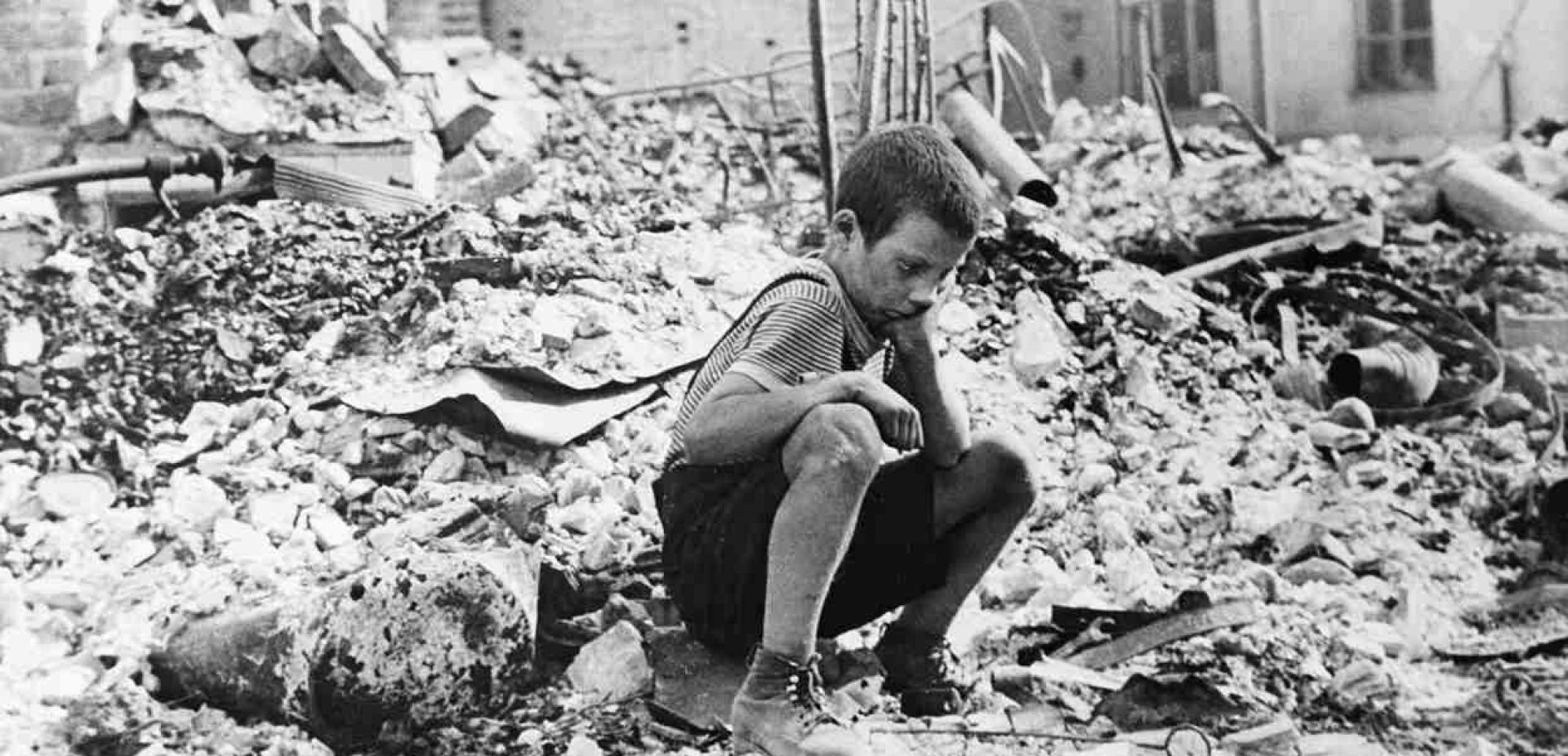

Short, stocky, with dictatorial tendencies, even in his cape Stefan Starzyński did not resemble a superhero. And it was not long before he would have been absent from fighting Warsaw. Although he continued to perform his duties as President in the early days of the September Campaign, he was awaiting a frontline assignment.

Like many of his colleagues from Sanacja milieu, Starzyński felt better in uniform than in a suit; during the First World War, he had fought as a soldier of the Polish Legions. So when he received his appointment to the 8th Heavy Artillery Regiment in Toruń, he had a clear plan: to prepare Warsaw for battle (building barricades, turning off the water and gas in the defensive sectors, etc.), hand over the city to his deputy - the continuity of power would be preserved - and then head for the front.

Why did he stay? One could say that he was given a new order - General Kazimierz Sosnkowski, who in September 1939 briefly acted as the coordinator of Warsaw's defence, instructed him "to remain on the spot [...], where he would be needed more than in the regiment". Starzyński heeded the call, and set about defensive preparations in earnest. He was widely known as a titan of labour, so the effects came almost immediately.

One must stand firm

Sosnkowski again: "At around 8.3 p.m., the briefing [with Starzyński's participation - editor's note] was over. [It was already two hours later that the people of Warsaw were working to build barricades, and crowds of civilians were streaming through the streets of the city, heading for the agreed assembly points".

This was overseen by Starzyński - President of the City, and from September 8th onwards Civil Commissioner to the Warsaw Defence Command. In wartime conditions, he proved to be an outstanding host, ensuring relative order and security in the capital. He was the one who set up a substitute for the police, the Citizen's Guard (at its peak, 7000 officers), who forced the opening of bakeries, pharmacies and banks that had been closed at the beginning of September, and who supervised the creation of a network of fire stations, etc.

His greatest fame, however, came with the speeches he made every day on the Polish Radio. Interestingly, before the war, he read almost all of his statements from a sheet of paper, and only came into contact with the microphone a few times at most.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

In September 1939, however, that did not matter - every radio appearance by Starzyński meant thousands of sets switched on and thousands of listeners lifted in spirits. How did he win their confidence? Naturalness? Sincerity? Charisma? Probably a bit of all, and he was listened to both when he spoke of the German tank captured by the women of Wola, and of the severe consequences for merchants who did not open their shops. And also when he apologised for his hoarse voice, as the voice is his main working tool....

Wearing a uniform (not a suit, despite the legend perpetuated in the film "Wherever You Are, Mr President", among others) and carrying a briefcase, he spent his days either officiating at Warsaw City Hall or visiting various locations around the capital. His home became his office. He infected everyone with optimism and the belief that Warsaw could defend itself long and effectively. He was so sure of this that he hardly could stand in awe of those calling for capitulation.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

In September 1939, however, that did not matter - every radio appearance by Starzyński meant thousands of sets switched on and thousands of listeners lifted in spirits. How did he win their confidence? Naturalness? Sincerity? Charisma? Probably a bit of all, and he was listened to both when he spoke of the German tank captured by the women of Wola, and of the severe consequences for merchants who did not open their shops. And also when he apologised for his hoarse voice, as the voice is his main working tool....

In September 1939, however, that did not matter - every radio appearance by Starzyński meant thousands of sets switched on and thousands of listeners lifted in spirits. How did he win their confidence? Naturalness? Sincerity? Charisma? Probably a bit of all, and he was listened to both when he spoke of the German tank captured by the women of Wola, and of the severe consequences for merchants who did not open their shops. And also when he apologised for his hoarse voice, as the voice is his main working tool....