The Prime Minister's organisational talent came in handy during the evacuation. On 7 September, at 2 a.m., he left Warsaw ("I take one last look at the Commandant's portrait and descend into the courtyard"). In Lutsk, he tried to control the growing chaos, even when the plan to stop the Germans on the line of the Vistula and then the Bug had failed, he still hoped that the card would turn. Only the Soviet incursion put an end to his illusions.

Składkowski saw nothing wrong with the escape of the government and command to Romania. He personally urged the hesitant Rydz to follow in the President's footsteps. There was, after all, a historical precedent: after the fall of the November Rising, politicians and generals emigrated to coordinate the struggle for sovereignty from Paris. That his compatriots at home, left at the mercy of the enemy, might resent their leaders was somehow not thought of. The bullish slogan "strong, united, ready" was smashed by German tanks.

Then it got even worse: under pressure from Hitler, the Romanian ally interned the ministers, while the French took the opportunity to force the resignations of Mościcki and Rydz. Sławoj wrote an application to join the Polish Army as a doctor. General Sikorski rejected his request, which was a symptom of the vindictiveness and small-mindedness typical of our politicians. Ironically, less than a week earlier, Składkowski had helped the future Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief when he ran out of petrol in the Romanian wilderness.

In the summer of 1940, Slawoj slipped away from the Romanians, having previously drowned 11 thick notebooks containing detailed notes of his time in state service in a lake and in a hotel toilet. He spent six months in Turkey at Sikorski's will. He was interrogated by an envoy of the commission investigating responsibility for the September defeat. In Palestine, the former prime minister managed to catch God by the feet - he became a sanitary inspector. However, after four months, he was dismissed from the Polish Army, as were other Piłsudski-ites.

The bad, the good, the loser

Condemned to inaction, which was against his nature, Składkowski engaged in one last battle: for memory. For a long time he wrote in a drawer, because the government forbade the printing of the confessions of the "gravedigger of the fatherland".

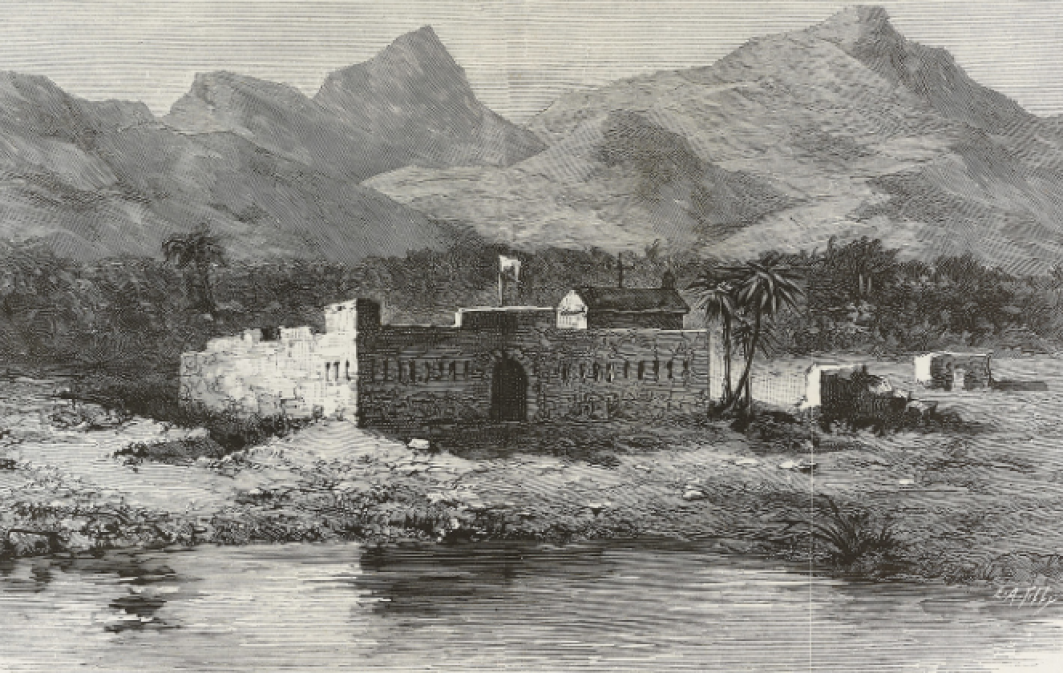

He spent his last years in London. Żermina was already dead, so he married for the third time - to Tadeusz Dołęga - Mostowicz's sister. Fate can be perverse. The author of "The Career of Nikodem Dyzma" was killed in Kuty, on the road leading to the bridge over the Cheremosh River, the same bridge by which the general had evacuated to Romania three days earlier.

Writing kept Slawoj alive, allowed him to endure the hopelessness of exile. "Administrative Flowers" - a memoir series that the Paris-based "Kultura" did not want to print - was published in the pages of "Wiadomości" ("The News"). Although the former Prime Minister developed his talent as an ironist and stylist, many compatriots were outraged that Mieczysław Grydzewski was lavishing praise on a Sanacja follower.

Składkowski died on 31 August 1962, on the eve of another anniversary of the outbreak of war. Cat Mackiewicz, who had earlier scoffed at the perpetrator of his stay in Bereza, came out with a confession that Sławoj was "a good man, a good soldier and a good Pole". The man himself, in his introduction to the book "Not the last word of the accused", expressed his conviction that history would judge him fairly. He forgot that history is written by the victors.

– Wiesław Chełminiak

-translated by Tomasz Krzyżanowski

TVP WEEKLY. Editorial team and jornalists

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE