How the Americans spied on the Soviets. Pre-war US intelligence in Poland and beyond

31.08.2022

Rich european socialite and - officially - the firstborn son of a wealthy family of brewers from St. Louis was in fact a Washington secret agent and - most likely - the illegitimate son of Prince Rudolph of Habsburg.

It is often said that information is power. Good information, of course, comes from credible sources. Uncommon intelligence from a century ago is the topic of this article. At the centennial of the story, many historians recognize a repeating pattern. Today, our headlines are full of stories from Ukraine and our intelligence sectors re scrambling to understand and forestall future disasters. Motivations for the conflict in Ukraine NOW are strangely similar to what they were then: it’s about natural resources, historical alliances, physical possession, and military supremacy.

Like most of Eastern Europe, Ukraine began the 20th century under Imperial rule. When Russia, Germany, and Austro-Hungary imploded with the Great War, the western bit of Ukraine was incorporated into re-emerging Poland. The bulk of Ukraine became the prize in a tug of war between Poland, Soviet Russia, and various White Russian armies. Putin is now using the greatest expanse of Russian territory as evidence that Ukraine “has always” belonged to Russia and has made it clear that he seeks to restore the Russian glory of old. For Americans, accurate intelligence was hard to come by 100 years ago from this largely unknown part of the world.

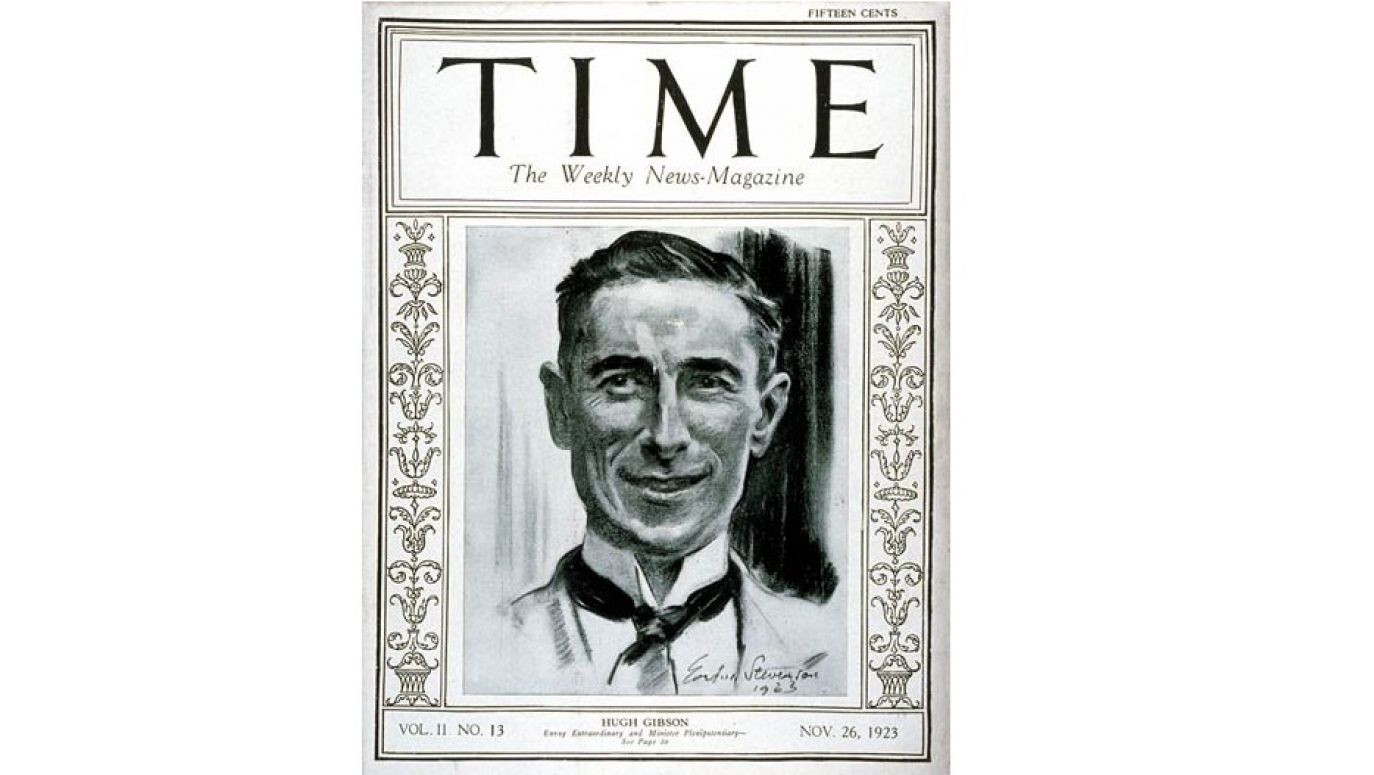

Some of the best information came through Poland during Hugh S. Gibson’s tenure as US Minister 1919-1924. Gibson’s experience during the Great War demonstrated his ability to gather, validate, interpret and disseminate intelligence.

After witnessing the German invasion of Belgium in 1914 and acting as diplomatic liaison between Herbert Hoover’s Commission for Relief in Belgium in 1915, Gibson was transferred to London to work at the heart of the diplomatic intelligence sector in 1916.

Strange Horodyski

When the US entered the war in 1917, Gibson was assigned as the diplomatic liaison to the war missions of Britain, Belgium and the Polish National Committee in Washington, DC. He served as aide to British Foreign Secretary, Lord Arthur Balfour. In addition to serving with earlier friends from Belgium, Gibson seized the opportunity to make the acquaintance of Polish musician Ignacy Paderewski. A world-famous pianist, Paderewski had immigrated to the US and was now lobbying for American involvement in World War I and the cause of Polish independence.

April 1918 found Gibson newly assigned to Paris with a wide variety of duties. His intelligence work continued as he served as the diplomatic liaison for General John Pershing and coordinated military intelligence with diplomacy under General Dennis Nolan. Forays to the front lines were interspersed with trips all over Allied-controlled Europe. To say that Gibson was “in the know” is an understatement!

Surprising him one day in Paris, Jan Horodyski, a member of the Polish War Mission Gibson had met in Washington the year before, turned up in Paris. He was a rather shadowy character who he loosely served with British Intelligence and offered Gibson insight which would soon be required in relation to Poland.

As the war turned in favor of the Allies during the summer of 1918, the Poles and the Czechs (as well as many other ethnic groups) created National Committees in Paris, in hopes of independent statehood. Gibson was assigned as the official US liaison to both the Polish and the Czech National Committees on September 26.

November 11, 1918. The Armistice halted the guns in Western Europe and Poland and Czechoslovakia emerged. Gibson continued his work with both as the mad scramble to set up nations in war-torn territory began. He also assumed the role of diplomatic advisor to Hoover and the emerging American Relief Administration. Intelligence remained a large part of Gibson’s work.

It fell to Gibson to debrief William Rose, a Canadian YMCA volunteer who had spent the war years near Krakow – and had vital information to share with the Allies.

Such was the quality of Gibson’s work in the intelligence sector that he was recruited to form and lead a new American intelligence network, based in Vienna, following the Armistice. He declined that honor.

Instead, Gibson accepted the appointment as the first US Minister to Poland in April 1919. He arrived in Warsaw just in time to witness the festivities for the first Polish Constitution Day in over a century on May 3. The Poles faced a variety of issues immediately threatening to newfound Polish independence. Undetermined borders that left critical resources such as coal in question, contentious internal politics, terrible humanitarian suffering, and an existential threat from Soviet Russia topped the list.

Naval commander Hugo Koehler

Like Paris, London, Vienna, and other major European cities, Warsaw turned out to be a central clearinghouse of intelligence. Gibson continued to obtain information from some unique and trustworthy sources who were stories in themselves.

One was American ace fighter pilot Merian Cooper who flew for and helped create the Polish Air Force as the Polish-Soviet war unfolded. Another was the ‘spy’ who worked with Gibson on intelligence about Russia in 1921-1922.

On December 17, 1920, US Navy Commander Hugo Koehler passed through Warsaw on his way home from a year of intelligence gathering behind the lines of the Russian civil war embedded in various Russian military camps.

Koehler’s incursions took him to cities such as Kiev, Odessa, Kharkiv, Sevastopol and Novorossiysk. We can immediately relate, 100 years later. The names of these towns are more well-known in the West NOW than they were in Koehler’s time.

In and around these towns, and in some places just recorded as “somewhere in Russia,” Koehler joined the camps of a wide variety of Russian warlords. He spent weeks at a time with White Russian generals such as Anton Denikin, Pyotr Wrangel, Alexander Kolchak, Nikolai Yudenich, and Alexander Kutepov. While these men had differing visions for the territory, they were all anti-Bolsheviks. From the depth and veracity of the information Koehler offered that December, Gibson immediately recognized Koehler’s value as a source of Russian intelligence and recruited him to serve as the Naval Attaché of the legation in Poland.

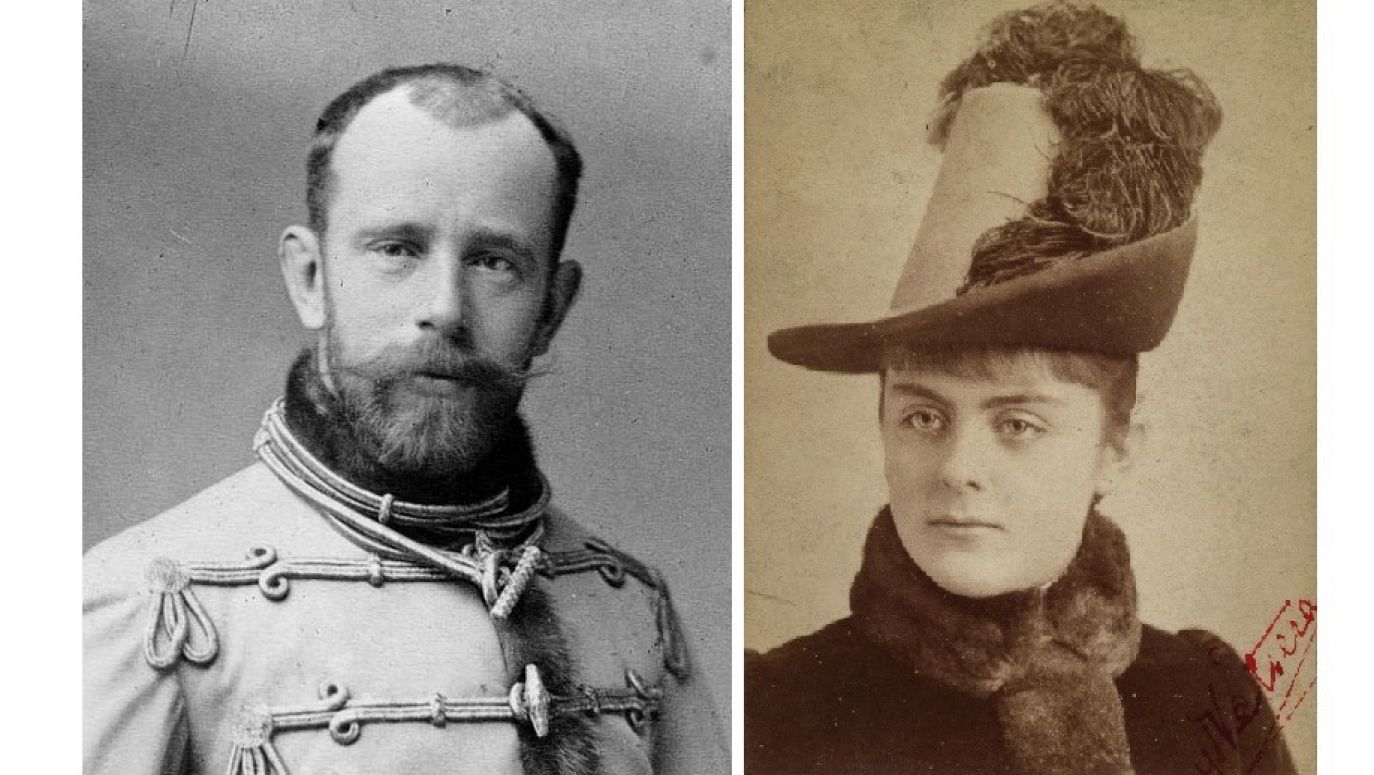

Illegitimate on of Rudolf Habsburg?

By the time he met Gibson in 1920, Koehler had already proven himself as a both a secret agent and a wealthy socialite. Before the CIA era, there was only Naval Intelligence. And Koehler was the top operative in southern Russia during and following WWI. Which explains the secret agent part. The wealthy socialite bit is a slightly more complicated…

As told by P. J. Capelotti in Our Man in the Crimea (1991), Koehler was officially the first-born son of a wealthy St. Louis beer brewing family. But there is a persistent rumor that he was, in fact, the illegitimate heir to the Hapsburg dynasty. Hugo’s paternal grandfather, Heinrich Koehler, Sr. (1828-1909) immigrated to the US from Germany in 1849. As a boy, Hugo traveled to Europe with his grandfather several times, being introduced to aristocrats and elites in London, Paris and all over the continent. This included being present to the Hapsburg court in Vienna. His grandfather stories, the introductions to various European royalty, and the Austrian trust fund that had been establish for Hugo (alone among his siblings) lends some credence to Heinrich’s version of Hugo true parentage.

Hugo was told that the Habsburg family set up the trust with the approval of the Vatican for his sustenance – because he was the illegitimate son of Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria, and his mistress, Baroness Mary Vetsera. Both Rudolf and Mary died in a murder/suicide at Mayerling in January 1889. It was posited that their son, Hugo (born in 1886), was spirited off to be adopted and raised by the Koehler family in America. The trust fund left for him was substantial enough to give Hugo the distinction of being the wealthiest man in the US Navy in 1909.

Sometimes the “American Dream” turned out to be an American nightmare…

see more

There is also a persistent rumor that Koehler helped to spirit the Russian Imperial Romanov family out of Russia in 1917. Guy Richards published the story of Koehler’s exploits in his 1975 Rescue of the Romanovs. There are many such theories of Romanov escape, but current forensic evidence appears incontrovertible – the Romanovs were all murdered by the Bolsheviks in central Russia on July 17, 1918.

Just to make this all a bit more credible, the research into Koehler’s biography was funded by Rhode Island Senator Claiborne Pell, best remembered for his Pell student grant program. As it turned out, Koehler married Pell’s mother Matilda in 1927, making him Pell’s step-father.

Naval Attaché and a spy

Koehler was duly assigned as Naval Attaché to Warsaw, arriving by summer of 1921. He immediately set about reactivating the contacts he had made earlier and building new sources. He and Gibson provided the intelligence that became the basis for US policy regarding Poland and her neighbors through 1922. A tense peace settled in Eastern Europe as the Treaty of Riga brought an end to the Polish-Soviet War in March 1921. Threats remained, however, from both Soviet Russia and Germany. Koehler’s war-time experience with both allowed for some very uncommon intelligence. Beginning in September 1921, Koehler’s reports were filed under Gibson’s Weekly Political Reports and published in An American in Warsaw (2018, in both English and Polish). The meat of these reports often bears an uncanny resemblance to today’s daily headlines.

The following excerpts are from these reports:

September 8, 1921

It was reported that both the Germans and Soviets had recently increased the belligerence of their propaganda against the Polish Government. Trotsky had recently announced that “war must be waged against Poland and against all other neighboring states by every means at the disposal of the Soviet Government except military operations, - by murder and terrorism, the fomenting of strikes and disorders, economic pressure and subversive propaganda.”

It was astutely noted that the similarity in German and Soviet rhetoric “raises the question as to whether there might not be an understanding between Berlin and Moscow aimed at the overthrow of the Polish Government.” Koehler and Gibson were acutely aware in 1921 of the danger threatening Polish independence. Eighteen years later, in September 1939, Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany did indeed conspire against Poland – and invade from both east and west. Have has a modern recurrence been avoided by Polish and German membership in NATO?

December 1, 1921

It became increasingly clear that Poland was getting mixed messages from her Western allies. Koehler traced the history of French encouragement for Polish military expansion. While the US and British strongly urged Polish military restraint, particularly in Galicia, the French took a more duplicitous approach.

Polish Prime Minister Paderewski reported to Gibson that “French Minister [Pralon] had advised him confidentially that the expressed wishes of the Peace Conference were not to be taken too seriously; that the Poles could go ahead and do as they liked counting upon the full support of … the French Government.” Meanwhile, Koehler reported that “French military authorities actively kept Polish apprehensions alive … The anti-Bolshevist-Ukrainian organizations working in Poland are hopelessly inadequate to overthrow the [Russian] Bolshevist regime, but they are sufficient to do serious harm to the country where they operate. I am reliably informed that these organizations are chiefly supported by the French.”

Many theories and many experts

February 2, 1922

Gibson discussed concerns raised by Western leaders that the Polish Government was deliberately Polonizing the western districts of Ukraine, focusing on land reform, education and especially the church. Gibson found that “there is evidence a very manifest desire on the part of the Polish Government to secure complete control of the Orthodox Church and its machinery in Poland; to take it entirely from under the control of the Hierarchy in Russia and perhaps even to endeavor to bring it under the direct authority of Rome. …”

The new Orthodox archbishop of Warsaw, Jerzy Jaroszewski (1872-1923), had served as archbishop of Kharkiv since 1919. He was generally disliked by the Poles and considered “extremely venal.” His known association with “the notorious Rasputin (1869-1916),” Russian mystic and confidant of the Romanov family generated further distrust. Gibson and Koehler reported “He seems to have come to some definite understanding with the Polish Government, the exact character of which I am not in a position to state. However, he has assumed the leadership of the Orthodox church in Poland and has carried on for some time the negotiations for a concordat.”

February 9, 1922

Koehler began this day’s report with quips about the various rumors about Russia circulating among leaders around the world.

“There are, it seems, about as many theories on Russia as there are so-called Russian experts, and as many schools as there are Russian centers abroad. … While these theories differ very widely from each other and are often quite irreconcilable, it is doubtful whether they do not differ quite as much from the real situation in Russia.” Among the catchphrases Koehler found across the various theories were “the revolution is over, evolution has begun” and “the famine is a blessing to Russia.”

Koehler completely dismissed the first phrase. About the second, he baldly stated that “real cause of the general starvation is simply that grain will not grow in a Communistic atmosphere.” Along with Gibson and Herbert Hoover, Koehler was an ardent anti-communist. Nevertheless, all advocated humanitarian relief regardless of the politics and worked with the various relief agencies under the umbrella of the American Relief Administration. At Hoover’s behest, the US Congress approved $20 million for foodstuffs in the Russian Famine Relief Act of 1921. Gibson remained proactive in facilitating Hoover’s activities based in Poland throughout his tenure.

Once again, the parallel to current events in Russia, Ukraine and Poland appear eerily similar. Propaganda and misinformation are swirling, unrest and fear are palpable, and war-related famines are threatening.

A Wedding, a Funeral and More Repeating Patterns

On Monday, February 20, Gibson and Koehler left Warsaw to make their way West. With Koehler at the wheel (Gibson never learned to drive!), they rode through the Polish and German countryside, gathering impressions and intelligence as they went. Their destination was Brussels, for the social event of the season – Gibson’s wedding to Ynés Reyntiens, daughter of Major Robert Reyntiens, Aide-de-Camp to Leopold II, King of the Belgians. Koehler and Rodrigo Villalobar, Spanish Ambassador to Belgium, served as best men. Following the wedding, Koehler returned to Poland while Gibson and Ynés combined a honeymoon with consulting in Washington and visiting his mother in California. The Weekly Political Reports continued in June.

June 15, 1922

Koehler addressed persistent rumors of Bolshevik preparations for another assault on Poland in spring 1922. It “become customary to start talk of a Bolshevik campaign every year in the Spring.” However, Koehler attributed much of the current angst to the “various threatening utterances by Lenin and Trotsky - which may quite well have been carefully calculated attempts to bluff western nations into a desirable state of mind ...”

There also was “a large concentration of Bolshevik forces on the Polish frontier in the Ukraine about the time the Genoa Conference was opening.” Also at issue was the French policy “keep alive unrest in this part of the world and apprehension as to the military menace from Russia.” After considering the gathered intelligence, Koehler concluded that there was nothing to indicate that the talk itself was based on any “serious aggressive intentions of the Bolsheviks.”

September 14, 1922

Koehler reported unrest in Galicia, where the Poles exercised actual control despite the still-undetermined status of the districts in the area we now know as Ukraine. The unrest was primarily among the Ruthenians who were being “encouraged by propaganda and assistance from outside sources to demand the creation of an independent republic.” Koehler also reported most “Ruthenian patriots” resided abroad. He found “little lawlessness and no evidence that the Poles are coercing the population. My information on this subject is from various sources, chiefly British, which can safely be assumed are not duly prejudiced in favor of the Poles.”

Meeting with z Chicherin

The last of Koehler’s reports was filed on September 28, 1922.

Soviet Russia’s Foreign Minister, Georgy Chicherin, visited Warsaw the preceding week. In addition to meeting with Polish officials, he met privately with Koehler. The Minister “began by discussing the possibility of revolutionary attacks upon the Soviet regime…” His deputy, Litvinov was “genuinely apprehensive of the aggressive intentions of Poland” only one month earlier. But Chicherin expressed confidence that “there was no ground for apprehension at present.”

Chicherin then launched into a tirade of criticism of the American government, “stating that he could make neither head nor tail of its attitude.” He complained that although Americans “possess a goodly measure of common sense… with regard to Russian questions they were behaving like school boys…” They “refused to look at facts as they were…”

Chicherin next “asked point blank” why America refused to cooperate with the Russian Government when it was “so favorable toward the Russian people.” Koehler replied that “it seemed rather obvious from repeated official statements that the American Government did not consider the Soviets as true representatives of the Russian people.” This generated another tirade about American school boy doctrinaires. However, Chicherin concluded by extending a friendly invitation for Koehler visit Russia and his own desire to go to the US.

Just learning: 12,000 species of plants in the garden, textbooks from London, physical instruments from Paris - all paid for with the grain of Volhynia.

see more

The last months of 1922 were eventful for Koehler, Gibson and Poland. In October Koehler attended a conference in Berlin to discuss closer cooperation between central and eastern European countries in preparation for his next assignments. He and Gibson worked closely with Polish Foreign Minister Gabriel Narutowicz, who would soon become Poland’s first elected president. On November 26, Gibson and his new wife, Ynes, endured the death of their tiny daughter. Another tragedy struck on December 16. President Narutowicz, on the 6th day of holding office, was brutally assassinated.

After a momentous 1922, Koehler moved on to his next naval assignment and a life that was full of drama, high society, and secret intelligence. Gibson went on to a distinguished diplomatic career. He never forgot his time in Poland, nor his friendship for the Polish people.

Perhaps the most striking element of the Gibson-Koehler intelligence is the similarity to that of today’s developments in Ukraine. Then, Russia displayed predatory behavior, employed ruthless maneuvers and engaged in misinformation campaigns. One hundred years later, we are seeing the same behaviors. For Ukraine, this has brought terrible suffering. For Poland, it has brought both a return of the old fear of invasion and the opportunity to shine in the face of a humanitarian crises.

While this century-old history can generate fear of repeating patterns, it also offers the opportunity to offer a different response to Russian behavior. There is hope! Both Ukraine and the world have changed.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Gibson retired from the diplomatic corps in 1938 rather than accept President Roosevelt’s appointment as Ambassador to Germany. For him, as for so many others, the handwriting on the wall was all too clear. Through the Second World War, Gibson again worked with Hoover to bring aid to Poles and other occupied nations. After the war was over, Gibson had one more chance to revisit Warsaw. At the behest of President Truman, Hoover set out on a world-wide blitz of information gathering about famine conditions threatening most nations in 1946. Gibson was recruited as his diplomatic liaison. Together, as volunteers and in their retirement, they traveled to over thirty-five cities across the globe in a ninty day period. At each stop, they interviewed kings, heads of state, agricultural officials, food controllers, import/export businessmen. Needs were assessed, surpluses analyzed, and quarrelsome questions resolved to get food moving toward hungry populations.

Gibson retired from the diplomatic corps in 1938 rather than accept President Roosevelt’s appointment as Ambassador to Germany. For him, as for so many others, the handwriting on the wall was all too clear. Through the Second World War, Gibson again worked with Hoover to bring aid to Poles and other occupied nations. After the war was over, Gibson had one more chance to revisit Warsaw. At the behest of President Truman, Hoover set out on a world-wide blitz of information gathering about famine conditions threatening most nations in 1946. Gibson was recruited as his diplomatic liaison. Together, as volunteers and in their retirement, they traveled to over thirty-five cities across the globe in a ninty day period. At each stop, they interviewed kings, heads of state, agricultural officials, food controllers, import/export businessmen. Needs were assessed, surpluses analyzed, and quarrelsome questions resolved to get food moving toward hungry populations.