The greediness of Frederick and Joseph, staring at him as if he was the son of the Empress of Austria, was not enough to tip the balance.

The partition surprised our elites. The Czartoryski family considered this course of action contrary to common sense. The King trusted the assurances of Catherine and her ambassador that the country would not suffer any territorial loss. In Warsaw, the outbreak of a Russo-Austrian war was expected rather than an alliance of the three black eagles. Nobody noticed that black clouds were gathering on the political horizon.

Versailles was busy saving Turkey, its traditional ally. Aid to the Confederates was treated as a useful diversion at Russia’s rear. If the ministers of Louis XV belatedly regretted something, it was that they did not demand an equivalent in the form of the Austrian Netherlands, so today’s Belgium. The maritime states: Great Britain, the Netherlands and Denmark, were perfectly indifferent to the fate of Poland.

At most, they worried that the balance of power in Europe would be tipped, and that Prussia would strengthen too much on the Baltic Sea. Therefore, they made it clear that they would not agree to the annexation of Gdańsk. In turn, the attention of Pope Clement XIV was preoccupied by the fate of the Jesuits, because, succumbing to the pressure of absolute monarchs, he agreed to dissolve the order, which had been the backbone of the papacy for decades.

It cannot be denied that the reputation of the Commonwealth of that time was tarnished as a country where Catholics persecuted other religions. Prussian and Russian propaganda inflated the problem of dissidents to monstrous proportions. It is hard to deny, however, that the Bar Confederates fought for the sovereignty of their homeland, but also for the preservation of the “golden freedom” and the privileges of the Church. When confronted with a better-armed and more disciplined opponent, they often panicked, dispelling the myth of the extraordinary bravery of the Sarmatians.

Political Fever

The 18th century began with the fall of the power of Spain and Sweden. Turkey was weakening. Former powers were losing their provinces but still existed. During the Seven Years’ War (1756-63) the dismemberment of Prussia was planned. The coalition wanted to give Ducal Prussia and Konigsberg to Poland in exchange for giving up Courland or some lands in the east. This conflict severely bled the Commonwealth’s neighbors and ended in a draw. Nobody gained anything, which frustrated the monarchs who aspired to greatness.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Berlin was most drawn towards annexation. Frederick wanted to consume Pomerania and Greater Poland “leaf by leaf like an artichoke”, but the obstacle was the hard non possumus of St. Petersburg. The situation was changed by the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War, which initially did not go according to the Tsarina’s wishes, and the crisis in Poland caused by the brutality of the ambassador (or rather the plenipotentiary) Nikolai Repnin.

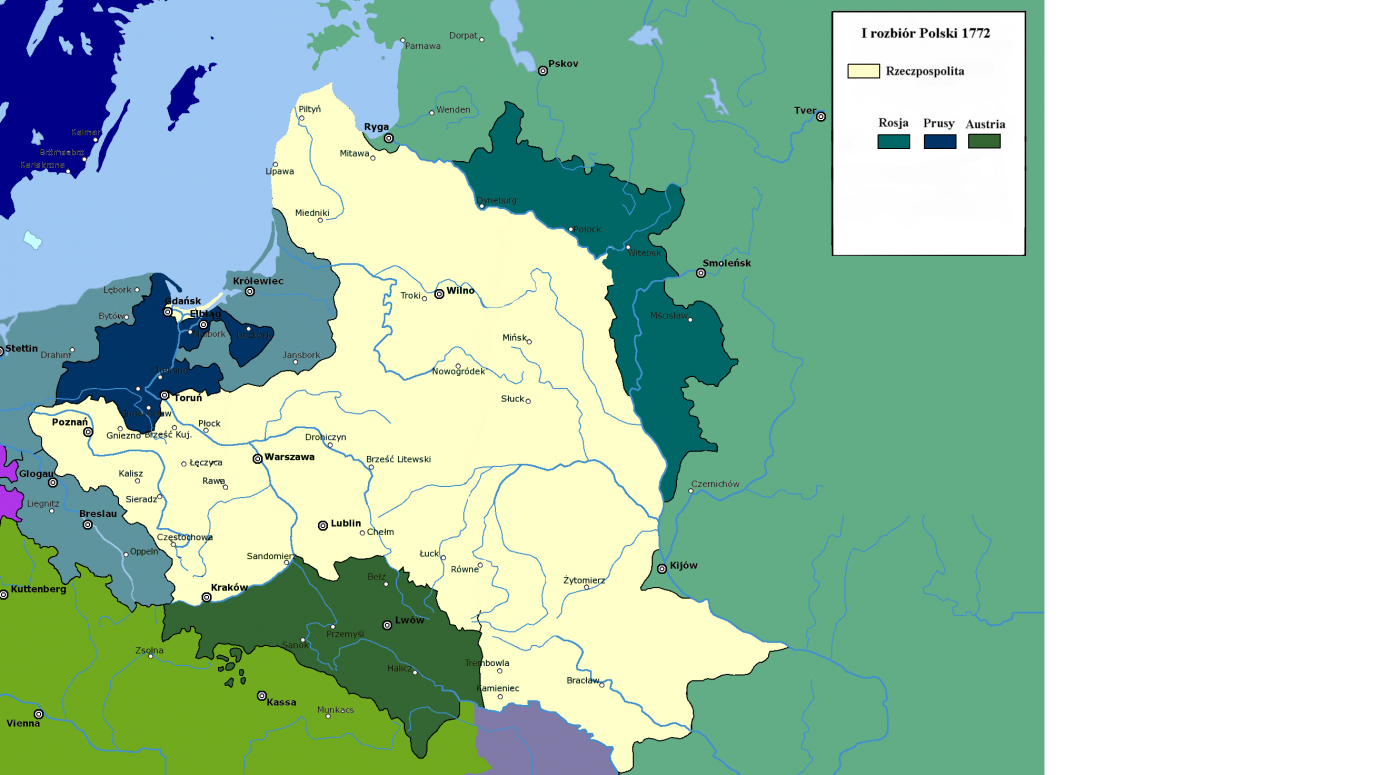

But who could have imagined that the Prussians would be aided by their mortal enemy – Austria? In Vienna, it was decided that the Habsburg monarchy deserved some compensation for the loss of Silesia. Under the pretext of counteracting the plague epidemic in the spring of 1768, the Austrians, in tacit agreement with District Governor Kazimierz Poniatowski, the king’s brother (who was more afraid of the Confederates than of the army of Her Apostolic Highness Maria Teresa), seized 13 towns in Spiš. Centuries earlier, they had belonged to Hungary, from which it was concluded that the Empress had the right to claim their return to the motherland. Appetite grows in proportion to consumption, so soon the “sanitary cordon” was extended to the Sącz region.

That was all the Prussians needed. Under the pretext of an alleged threat from the Confederates, they entered Pomerania and Greater Poland, unlawfully enforcing quotas, contributions and tributes. Sometimes they paid for requisitioned grain, but with counterfeit coin.

The brother of the Prussian ruler, Henry, set off to St. Petersburg to convince the Tsarina that the best way to calm Poland was to divide it. To his surprise, he met with understanding.

Frederick’s subordinates began to frantically search the archives for documents that would allow for the border to be moved as far east as possible. To little effect. “The more carefully this subject is studied, the more the weaknesses of our claims are revealed,” the official reported.

The stance of Russia, which so far treated the Commonwealth as a buffer state, was of key importance. Catherine put vengefulness above the raison d'état. Did the annexation of Courland, Polish Livonia and the eastern parts of Belarus (called the “straightening” the border) have to be accompanied by the distribution of territorial gifts to the Habsburgs and Hohenzollerns? Even the Tsarina’s lovers had their doubts.

Anarchists Versus Barbarians

In the summer of 1771, the Prussians and Russians reached an agreement and together put pressure on Austria. Maria Teresa shuddered, saying that she did not understand the policy of when two use violence to oppress an innocent, the third is to imitate them for the sake of balance. Besides, the aging empress hated Frederick, and she considered it a mistake to come to terms with this utter cynic. Joseph did not share his mother’s pacifism. He pressed for the alliance with Turkey and was pained to hear about the successes of Catherine’s generals on the Danube.

He himself would have preferred to gain strength in Germany, but the economic situation was bad, so all that was left was to take what they could in Poland. Austria was bidding high. In order to strengthen its bargaining position, it put an army on standby that did not have to be used in the Balkans.

The bargaining of the three black eagles fair delayed the partitions for a full year. On July 24, Panin supported leaving Wieliczka and Lwów to the Commonwealth, but finally relented. The Austrian idea to give Poles a piece of Wallachia, to wipe their tears with, also did not pass. The enlightened monarchs showed their true, unpowdered faces. The partition was a dangerous precedent, small states and nations treated it as a memento. To liberals, it seemed to be contrary not only to morality but also to international law. Montesquieu condemned the empires destroying their weaker neighbors

Since Poles were found who were demoralized enough to build their careers and fortunes on the destruction of their homeland, it should not be surprising that fans of enlightened absolutism – such as Voltaire – kicked the prostrate person while praising the bandits. However, it is worth quoting the opinion of David Hume who, after the first partition, regretted that two civilized nations (Poles and Lithuanians) were falling into decline, and that “the barbarians, Goths and Vandals from Germany and Russia are growing in power and strengthening themselves.”

These were heralds of a shift in European public opinion. It came too late to save the Commonwealth, but it was important capital for the future. The partitioners lost the battle for memory, their solidarity collapsed. The Prussians began to blame the Austrians, the Austrians – the Russians. In Histoire de l’anarchie de Pologne [The History of Anarchy in Poland] published in Napoleonic times (French diplomat Claude Rulhière started writing it before the first partition), our country was called a barrier against eastern barbarism, which threatened all of Europe. The idea of the rampart has returned in a new version.

– Wiesław Chełminiak

TVP WEEKLY. Editorial team and journalists

– Translated by Nicholas Siekierski

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE