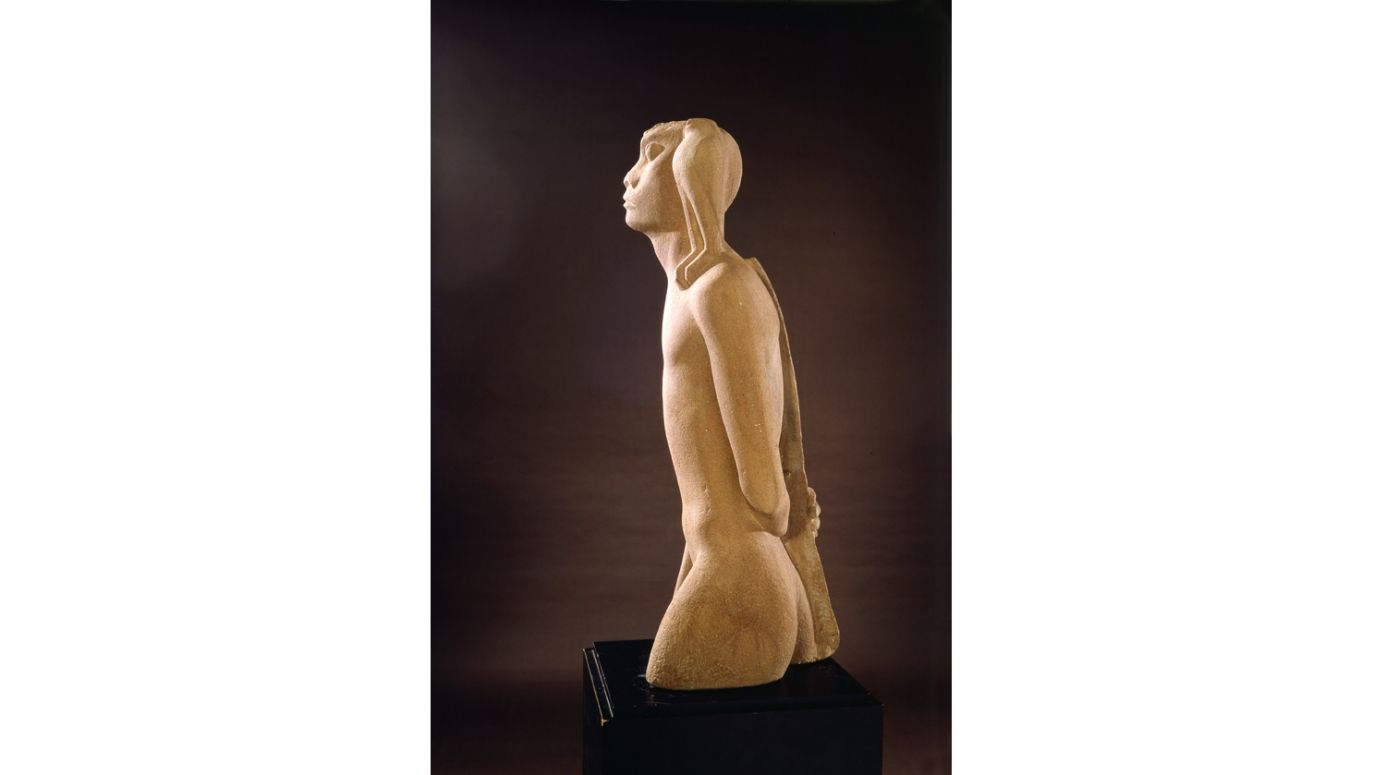

The influence of “Canaanism” on the works of Hebrew artists from Palestine at the end of the 1930s is intriguing. For example, the visualization of primitivism present in their work expressing a fascination with the ancient paganism (or, to put it bluntly, idolatry) of the Middle Eastern peoples. An example is the sculpture “Nimrod” by Yitzhak Danziger. For Poles, it may evoke associations with the works of Stanisław Szukalski, referring to nationalist and neo-pagan ideas.

Fruit of an ancient oak tree

Returning to “Minotaur”, the novel echoes “Canaanism” in the dreams of Nikos Trianda. He is a Greek from Alexandria (an Egyptian city symbolizing the cosmopolitanism of the Hellenistic era) who scientifically deals with the cultures of the Mediterranean basin. Once, while in Israel, he becomes suspected of contacts with a Greek Orthodox priest who is accused of helping Arab terrorists.

Nikos is interrogated by Alexander Abramov. One gets the impression that he finds a kindred spirit in him. This is what happens when Nikos tells him about the culinary links between the nations of the Mediterranean basin: “Oil in humus and broad beans, lamb ribs on the fire or pickled grape leaves stuffed with rice and meat, all this was offered to me in Athens, Alexandria, Limassol, Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. And from what I know, they would also offer me the same in Damascus, Constantinople and Tunis”. Later he adds: “I am not an ordinary Levantine with Greek roots, but a fruit of the ancient oak tree”.

Finally, it is worth quoting fragments from “Minotaur” which reveal Alexander’s “Canaanite” dilemmas regarding Jewish-Arab relations. Here is one of his thoughts: “The Arabs whom I actually abuse because they fell into my hands defeated and bound, who are they if not the same Arabs who worked in the yard of our house; these are the same Arabs with whom I chased hares”.

Then we read about Alexander’s longings: “I would give ten American, English or French friends for friendship with an Arab. I can drink whisky with a European, do business with him, conclude contracts with him, because, after all, the State of Israel is actually a European subsidiary in the East. With an Arab, however, I can return and roll on the ground, inhale the smell coming from the furnace burning with goat dung, collect and chew marjoram, run towards the horizon and find there my own childhood or the meaning of life, which are now almost elusive, also in this place, where the hill from my childhood rises”.

Certainly, the “Canaanite” idea is a historical, retrospective utopia (just like the Polish neo-pagan “rodzimowierstwo” – “indigenous religion”). That’s why its implementation had no chance of success. But what Benjamin Tammuz wrote about Jewish-Arab relations in “Minotaur” isn’t detached from reality. Alexander Abramov’s thoughts are not mere literary fiction. Supposedly, there is much more truth in them than in media reports that reduce the conflict between Jews and Arabs to a simple Western-style story of good versus evil. And this is so, regardless of the roles in which we cast for the two sides in this confrontation.

– Filip Memches

TVP WEEKLY. Editorial team and jornalists

– Translated by Dominik Szczęsny-Kostanecki

Benjamin Tammuz „Minotaur”, z języka hebrajskiego przełożył Michał Sobelman, Wydawnictwo Claroscuro, Warszawa 2021

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Here we come to the weakness that characterises Alexander. It is succinctly described by his teenage friend, Nachman. When they are both adults, they establish cooperation. Nachman is an adviser to the Israeli Minister of Defence. After reading Alexander’s file, he notes that while the attached profile is generally correct, the psychologists who examined him didn’t notice one important characteristic – “melancholy, tendency to give up on life, flirtation with death”.

Here we come to the weakness that characterises Alexander. It is succinctly described by his teenage friend, Nachman. When they are both adults, they establish cooperation. Nachman is an adviser to the Israeli Minister of Defence. After reading Alexander’s file, he notes that while the attached profile is generally correct, the psychologists who examined him didn’t notice one important characteristic – “melancholy, tendency to give up on life, flirtation with death”.