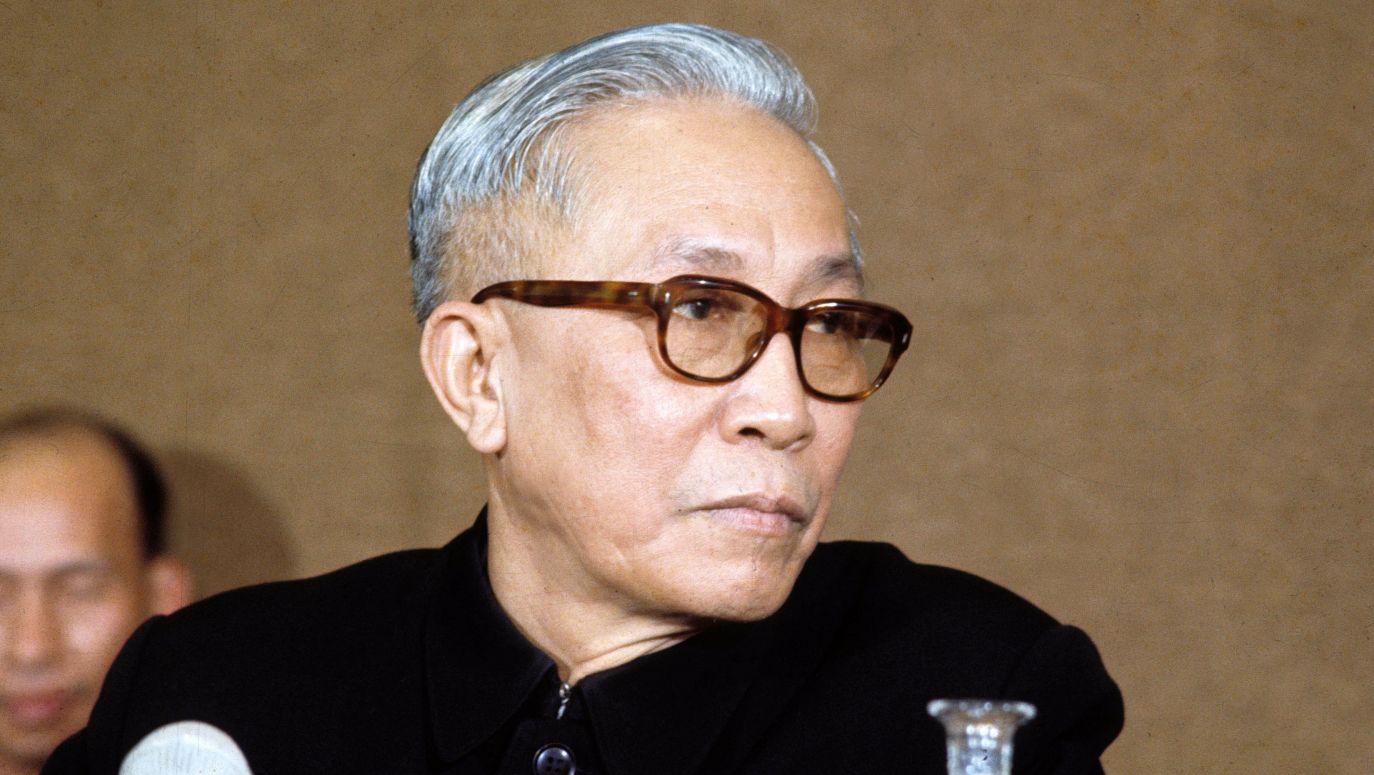

At the age of 16, he became involved in the liberation struggle, which Kissinger would later consider to be evidence of fanaticism and assess Thọ as an uncompromising man. And at the same time well-mannered, cultured and polite. Kissinger was irritated by his sense of superiority when he maintained from the beginning of the negotiations that North Vietnam was the only true Vietnam and that the Americans were barbarians trying to delay the inevitable, that is, the unification of the country under a red banner with a five-pointed star.

Thọ was born at the right time to fight. Already in the 1930s, the communists gained the upper hand in the Vietnamese liberation movement fighting the French and became one of them. In 1930, he co-founded the Indochinese Communist Party. He organized strikes and led students. He was arrested and spent six years (1930-1936) in the harshest prison in French Indochina on the island of Poulo Condore (Côn Sơn) in the South China Sea. This hardened him and after his release, he continued to engage in subversive activities, for which he was again imprisoned for five years (1939-1944). The French kept him in a “tiger cage”, where there was dirt, stench and hunger. On the other hand, legend says that Thọ and the other Vietnamese political prisoners studied literature, science and foreign languages in prison. Surprisingly, the object of their admiration was France, which they considered a country of high culture worth imitating. They even performed comedy plays by Molière as a tribute!

After his release – or, as legend has it, his escape – Thọ again led the fight against the occupiers, this time the Japanese. He founded the guerrilla Vietnamese Independence League, the Viet Minh, which became the Vietnamese People’s Army – in time he would become its general. In August 1945, an anti-Japanese uprising broke out, and in September, Hồ Chí Minh, the leader of the northern communists, proclaimed the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Japan gave up its claims to the territory, but France had no intention of losing its colonial empire. Several years (1946-1954) and bloody clashes began, known as the First Indochina War – Thọ was one of the commanders – after which the French signed a peace treaty and also withdrew from Vietnam. As a hardliner, Thọ was among the leaders of the Communist Party of Vietnam: he sat on its Politburo from 1955 (until 1986).

The Geneva Accords of 1954, ending the First Indochina War, temporarily divided Vietnam along a demarcation line drawn along the 17th parallel. In the north there was the communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam, supported by the Soviets and the Chinese, and in the south – the anti-communist Republic of Vietnam, led by President Ngô Đình Diệm, who was associated with the Americans. According to the decisions of Geneva, the future fate of both countries was to be decided by elections held by July 20, 1956, but Diệm cancelled them, justifying the decision by the lack of possibility of fair voting in the north for political reasons (although he was rather afraid of defeat in the clash with Hồ Chí Minh). The USSR and the PRC suggested that both countries be admitted to the UN. The United States proposed to leave matters to the Vietnamese people.

But the North Vietnamese decided to play for the whole pot. In 1958, at the 15th plenum of the party – in defiance of Hồ Chí Minh, who dissuaded his comrades from provoking Diệm, because it was too early for a revolution – they supported the communist uprising against the government in Saigon. The operation was led by General Thọ. First, local guerrillas organized attacks on representatives of the administration. In 1959, the transfer of North Vietnamese soldiers began. The construction of the so-called Hồ Chí Minh Trail, which was used to transport troops and supplies from the North – through the communist-controlled areas of Laos and Cambodia – to the South. Thọ was then hiding in South Vietnam, from where he supervised all activities. He also created the Viet Cong, communist guerrilla units that became famous for putting up active resistance. In the 1960s, their number increased from 10,000 to even 130,000 fighters, often pretending to be peasants during the day and fighting at night to camouflage themselves. Fighters were recruited to support the Viet Cong from socialist countries, including the Polish People’s Republic, where several dozen volunteers volunteered, but there is no evidence that they were eventually sent into battle.

Initially, the US was not interested in the region. In 1961, however, the threatened Diệm turned to the newly elected president, Democrat John F. Kennedy, for help, and soon a ship with 1,500 marines and combat helicopters arrived at the port of Saigon. The fear began to prevail among American politicians that the communists taking over all of Vietnam would be a step towards their taking over the territory of Asia. It was decided to increase political, financial and military support. In 1964, the new Democratic president, Lyndon B. Johnson, sent thousands more uniformed officers to Vietnam. He agreed to massive bombing of the North and communist strongholds in the South, particularly along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail. As part of Operation Rolling Thunder, during carpet bombing, the Americans destroyed the jungle that supported the Viet Cong with napalm, killing civilians in the process.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

The Viet Cong successfully avoided attacks because the partisans knew in advance the targets of the bombings and the directions of the American attacks. The information was provided to them by Soviet military intelligence thanks to reports from its agent John Anthony Walker, who provided encryption codes for the cryptographic device, thanks to which over a million American ciphertexts were read. Walker worked for the KGB and GRU until 1985, when he was exposed by the FBI and arrested for espionage. Ironically, isn’t he another unsung hero of the Vietnam War who contributed to peace and perhaps also deserved a Nobel Peace Prize alongside Kissinger and Thọ?

It became clear that the American landing in Vietnam wouldn’t achieve much. Support for Johnson’s policies waned, and in the spring of 1968 he announced that he would not stand for election again. In November, Republican Richard Nixon won, largely because of his promises to end American involvement in the conflict. In fact, as an opponent of communism, he believed that the sudden withdrawal of troops from Vietnam and the resulting inevitable communist victory would be too much damage to American prestige. He sought an honorable exit so that it would not look like failure – he began to gradually reduce the American presence in Vietnam and continued the peace talks started by Johnson. And at the same time it bombed Hanoi to increase the pressure in the negotiations.

Kissinger and Thọ’s secret conversations had some heated moments. In April 1970, the Vietnamese interrupted a meeting with the American because “there was nothing to talk about”. An attempt to schedule another one in May was rejected. “Your assurances of peace are just empty words,” Thọ said. He came to the table a year later to insist on the removal of the next president of South Vietnam, Nguyễn Văn Thiệu. Kissinger refused and replied that Nixon would soon warn Chinese leader Mao Zedong that the days of supplying weapons to North Vietnam were coming to an end. Thọ replied, “What you say will have no influence on our attitude. Our task is to continue the fight that will decide the outcome of the war in my country’s favour”. Point for Vietnam.

The thirteenth meeting took place on May 2, 1972 in a hostile atmosphere, because the communists had occupied a piece of South Vietnamese territory and seemed to be pushing hard against the enemy. Nixon had previously advised Kissinger: “No nonsense, no niceness”. The American kept his cool, but when during the conversation Thọ mentioned that Senator William Fulbright was criticising the American president’s administration in connection with the war in Vietnam, Kissinger sharply commented on his words: " Our domestic discussions are no concerns of yours”. Thọ replied dispassionately: “"I'm giving an example to prove that Americans share our views”. Point for Vietnam.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

The Viet Cong successfully avoided attacks because the partisans knew in advance the targets of the bombings and the directions of the American attacks. The information was provided to them by Soviet military intelligence thanks to reports from its agent John Anthony Walker, who provided encryption codes for the cryptographic device, thanks to which over a million American ciphertexts were read. Walker worked for the KGB and GRU until 1985, when he was exposed by the FBI and arrested for espionage. Ironically, isn’t he another unsung hero of the Vietnam War who contributed to peace and perhaps also deserved a Nobel Peace Prize alongside Kissinger and Thọ?

The Viet Cong successfully avoided attacks because the partisans knew in advance the targets of the bombings and the directions of the American attacks. The information was provided to them by Soviet military intelligence thanks to reports from its agent John Anthony Walker, who provided encryption codes for the cryptographic device, thanks to which over a million American ciphertexts were read. Walker worked for the KGB and GRU until 1985, when he was exposed by the FBI and arrested for espionage. Ironically, isn’t he another unsung hero of the Vietnam War who contributed to peace and perhaps also deserved a Nobel Peace Prize alongside Kissinger and Thọ?