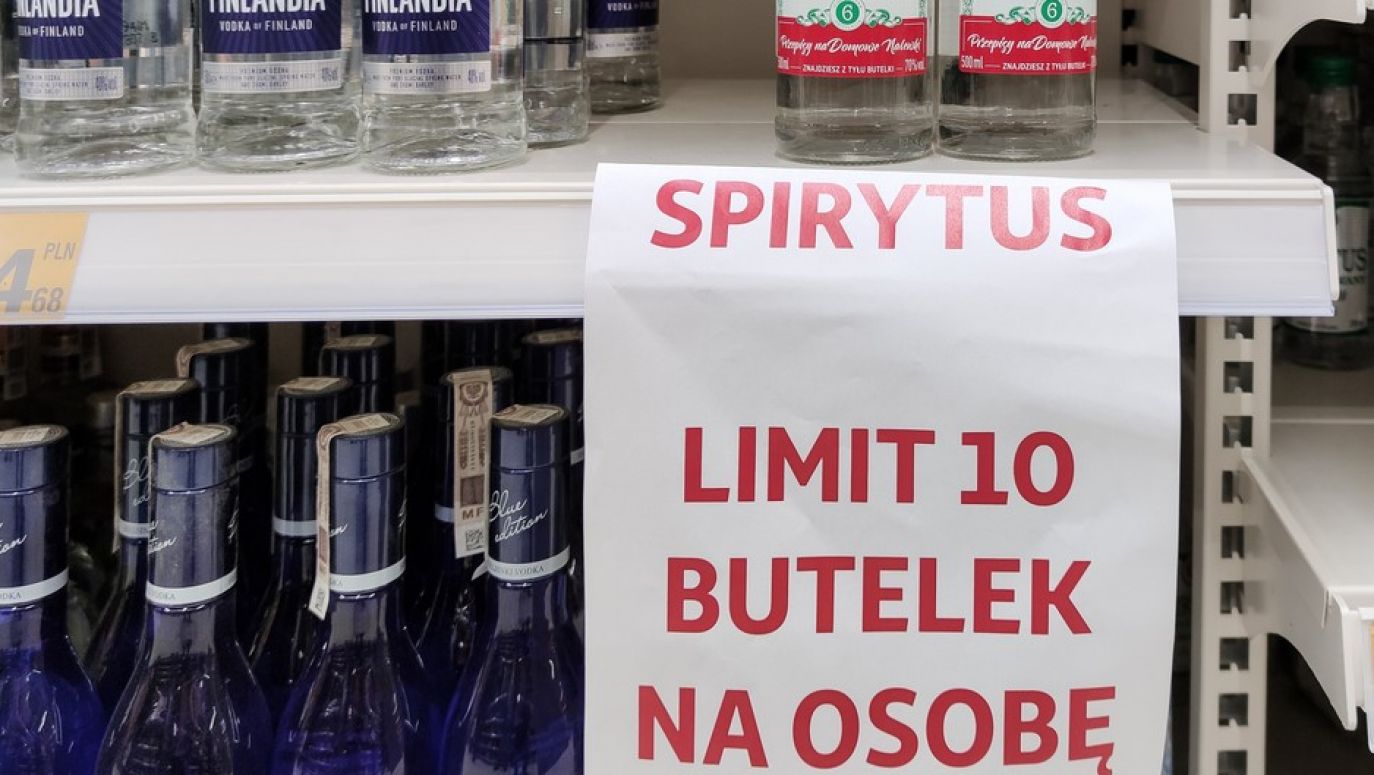

Of course, when the real war started, all these supplies were immediately sent to Ukraine. I was only left with those five litres of denatured alcohol, and I still don’t know what to do with it.

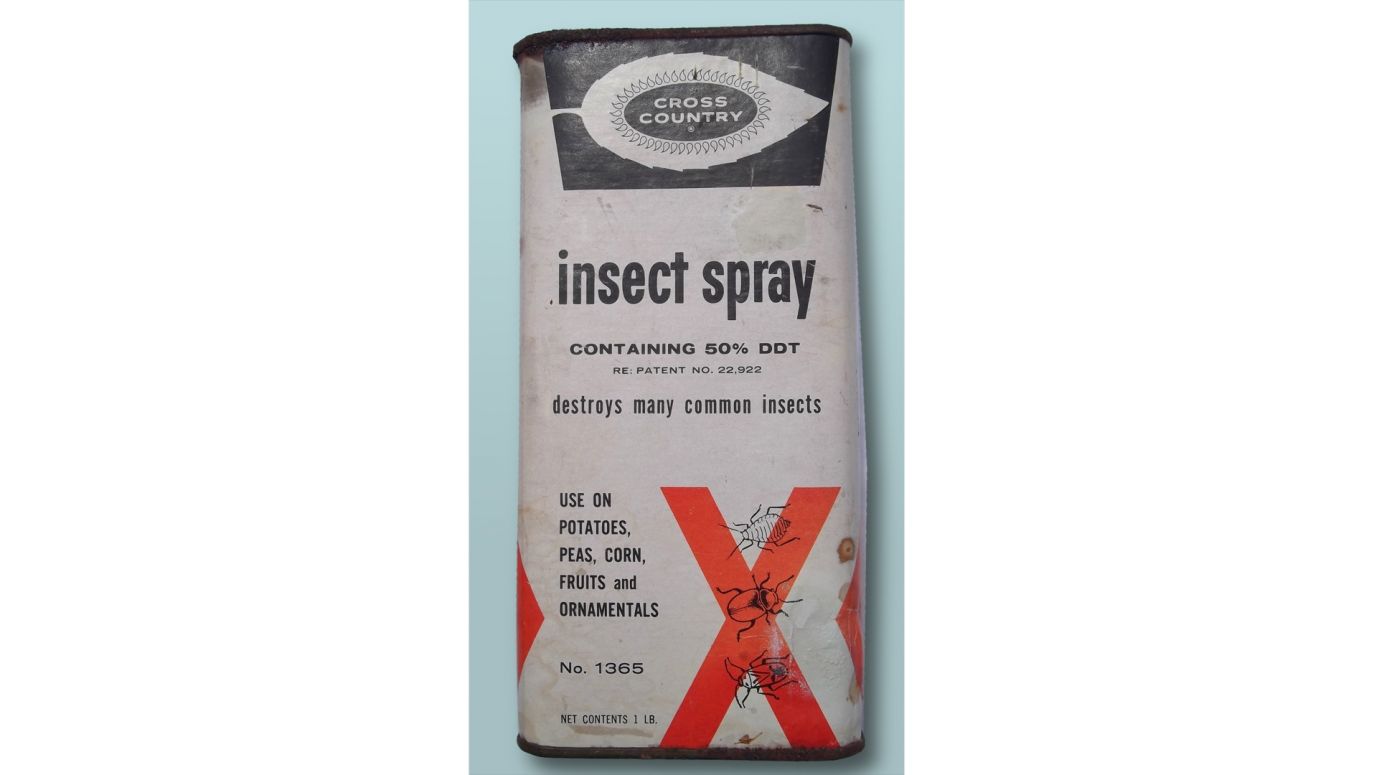

A package of DDT

My father, after wartime experiences, hated pests. They must have tormented him terribly during the German occupation. He even claimed that Americans won the war thanks to DDT. In his stories, it was the most terrifying weapon against enemies and pests. And at the same time, the most wonderful one, bringing relief and victory.

Germany didn’t have DDT. So they had to lose the war decisively.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

When the world faced the threat of a new war, my father was in America. The Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 heralded terrifying events. The global outlook wasn’t exactly rosy, as everyone feared it would be the first and last nuclear war.

We, my sister and I with our mother, were then near Warsaw. I think we were even sick, as mom couldn’t leave the house when everyone was buying up flour, groats, and sugar from the stores. In the event of that third world war, we were left without any provisions.

There, far away from us in America, the father sat, designing skyscrapers and fearing that we would be attacked by an invasion of various pests and microbes. He decided that in this war, his children would not suffer from pests. No vermin had the right to bite us and infect us with a contagious disease. So he bought a package of DDT and sent it as quickly as possible to our country, before a global front line could separate us. That’s how we got this wonderful agent, and thanks to it, we had a chance to survive this war.

Many years later, after the death of the father, in the attic of the parents’ apartment, I found a deeply hidden package of DDT. It had been there for over 40 years – a box of hope for survival in the harshest wartime conditions.

On the other hand, my wife’s grandmother kept food supplies in a sofa bed. It later turned out that they were lying next to Azotox, the Polish equivalent of DDT. Azotox had been there for years because such a measure should be as close as possible in case of war danger. People who survived the occupation nightmare were afraid of two things: hunger and disease-spreading insects.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE