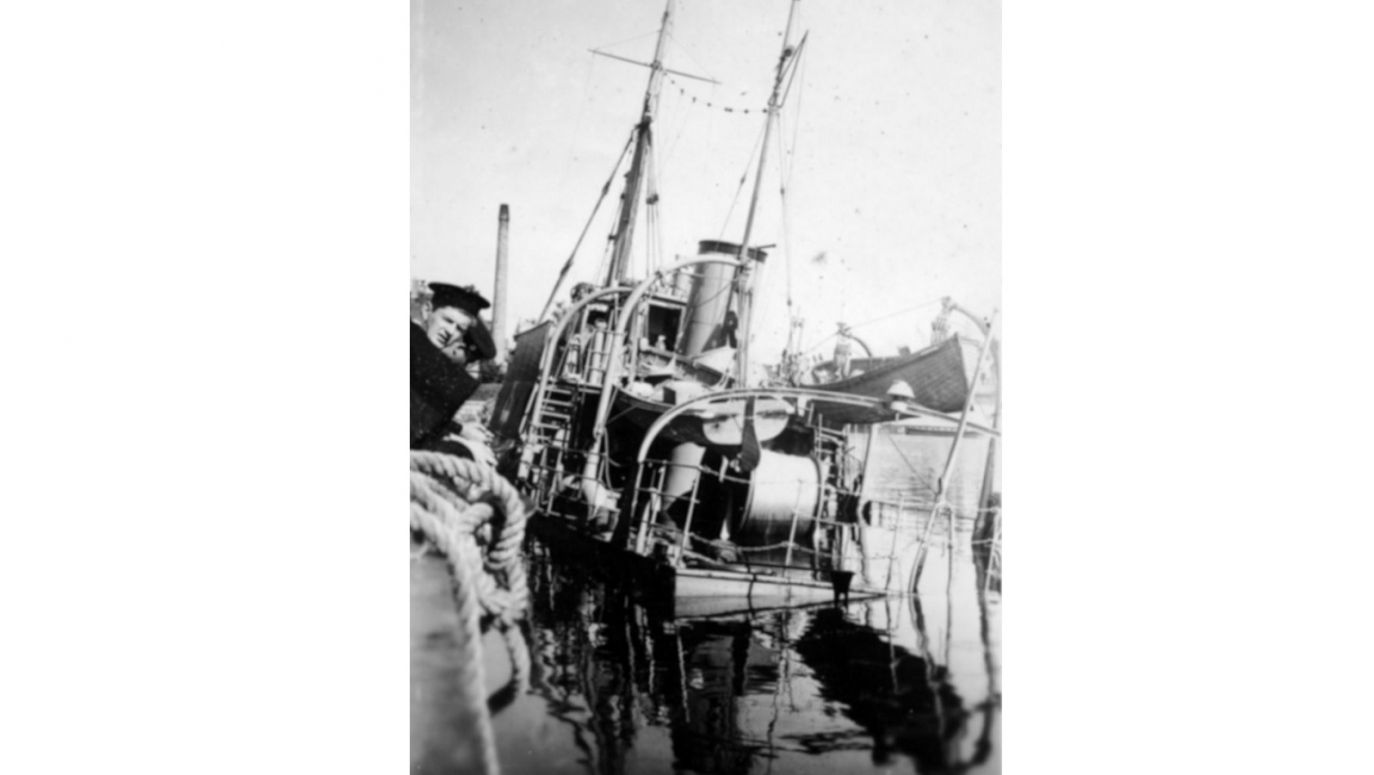

The commander of the minesweeper “Havkatten” behaved differently (previously a torpedo boat, built in 1918, equipped and armed like “Hajen”). Lieutenant Poul Würtz made a successful attempt to break through to Sweden. It was similar in the case of the small MS 1 minesweeper (74 tons of displacement, 1 20 mm cannon and 2 machine guns). When its commander received a coded telegram on 28 August ordering “high readiness”, the unit was near Mariager in the east of Jutland. She reached another, small port, the sailors painted the ship with tar (!) and covered the cannon, and on the side they wrote the name “Sorte Sarma” (“Black Sarah”). They successfully avoided arrest by the Germans and reached Trelleborg. Later, a dozen ships formed the “Danish Flotilla” in Sweden.

During Operation Safari, 25 Danes were killed and about 53 wounded; German losses were similar. Shortly thereafter, the Danish government resigned, finding it unable to run the country. Ministries were run by top officials, so it was said that a “government of department directors” had been formed. Events in Denmark in 1943, including photos from Copenhagen Holmen, can be viewed

in a short American video on YouTube.

Toulon drama

The Danes knew perfectly well what the Germans could do, because just over half a year earlier the French fleet had sunk in Toulon. The difference was that, compared to the German forces, the Danish forces were very weak; the French, defeated in the war, still had a powerful navy.

After the armistice of June 22, 1940, part of France remained unoccupied. It is true that the navy was to be disarmed, but after the British attack on the Algerian port of Mers el-Kébir (in July 1940, the British destroyed one battleship there and damaged several ships, and 1,297 French sailors died in British shelling) and Dakar (a modern battleship “Richelieu” was damaged), the Germans allowed the French to leave some of their units in combat readiness.

On November 8, 1942, the landing of Allied troops in North Africa began. On November 27, 1942, the Germans entered previously unoccupied French territory, leaving Toulon and its base under French control. But at the same time they planned to seize this base and its ships.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

The army and the fleet went continued to operate (unlike the air force, which was destroyed by the Germans in the 1940 attack) and carried out military manoeuvres. The warships were only engaged in clearing the coastal waters of mines and could only sail freely in basins designated by the German command – but this was normal training, with live ammunition being fired ( watch the heavy guns of the battleship Peder Skram being fired on YouTube).

The army and the fleet went continued to operate (unlike the air force, which was destroyed by the Germans in the 1940 attack) and carried out military manoeuvres. The warships were only engaged in clearing the coastal waters of mines and could only sail freely in basins designated by the German command – but this was normal training, with live ammunition being fired ( watch the heavy guns of the battleship Peder Skram being fired on YouTube).