"But, if war does break out your way, what do you think," we ask curiously, "what will happen?" "What will happen? - cheerfully picks up a young lawyer, a reserve officer - In ten days we will be in Warsaw." And again I feel sad. This young Pole, talking with such calmness and even cheerfulness about the fact that he will have to put on the hateful Prussian uniform and enter Warsaw in it, is so terrible in his Polish tragedy - perhaps the most terrible in a century....

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

The first anniversary of the outbreak of the war [the First World War] had just passed and the newspapers were full of articles calling for the writing of diaries and the 'preservation for posterity' of even small memories. I think by then everyone was beginning to feel more and more tangibly that the world was changing more and more and that people were being thrown further and further out of their former equilibrium. We were increasingly beginning to accuse the ongoing war - "terrible, bloody, relentless", "gouging deep scratches in our souls" - of this confusion of the fates of countries, nations and individual people. "More than once," I wrote at the beginning of the diary, "we asked ourselves after waking up, 'is this perhaps just such a cruel dream of a long, bloody and pathetic war?' Alas, it was not a dream, and perhaps that is why there was a desire to collect, sort and summarise the facts, to understand how it was that we had succumbed to the violence of the great storm. For there was a huge discrepancy between the hopes Poles had attached to the outbreak of the long-awaited war and the reality and surprises the war brought with it. This war had been prayed for since the time of Mickiewicz, and it was most often discussed by "compatriots", but it seems that almost no one understood the real reasons that brought about the war. That is why, when I look back now from the perspective of the past years, the views and behaviour of Polish society seem to me not only naive, but downright funny.

The first anniversary of the outbreak of the war [the First World War] had just passed and the newspapers were full of articles calling for the writing of diaries and the 'preservation for posterity' of even small memories. I think by then everyone was beginning to feel more and more tangibly that the world was changing more and more and that people were being thrown further and further out of their former equilibrium. We were increasingly beginning to accuse the ongoing war - "terrible, bloody, relentless", "gouging deep scratches in our souls" - of this confusion of the fates of countries, nations and individual people. "More than once," I wrote at the beginning of the diary, "we asked ourselves after waking up, 'is this perhaps just such a cruel dream of a long, bloody and pathetic war?' Alas, it was not a dream, and perhaps that is why there was a desire to collect, sort and summarise the facts, to understand how it was that we had succumbed to the violence of the great storm. For there was a huge discrepancy between the hopes Poles had attached to the outbreak of the long-awaited war and the reality and surprises the war brought with it. This war had been prayed for since the time of Mickiewicz, and it was most often discussed by "compatriots", but it seems that almost no one understood the real reasons that brought about the war. That is why, when I look back now from the perspective of the past years, the views and behaviour of Polish society seem to me not only naive, but downright funny.

In the tropical zone time counts were shorter than what constitutes our year -- e.g. 260 days.

see more

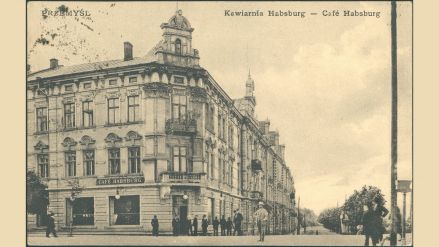

The multinational Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria celebrates its 250th birthday.

see more

The idea was to cut off the branches and hold the current together

see more