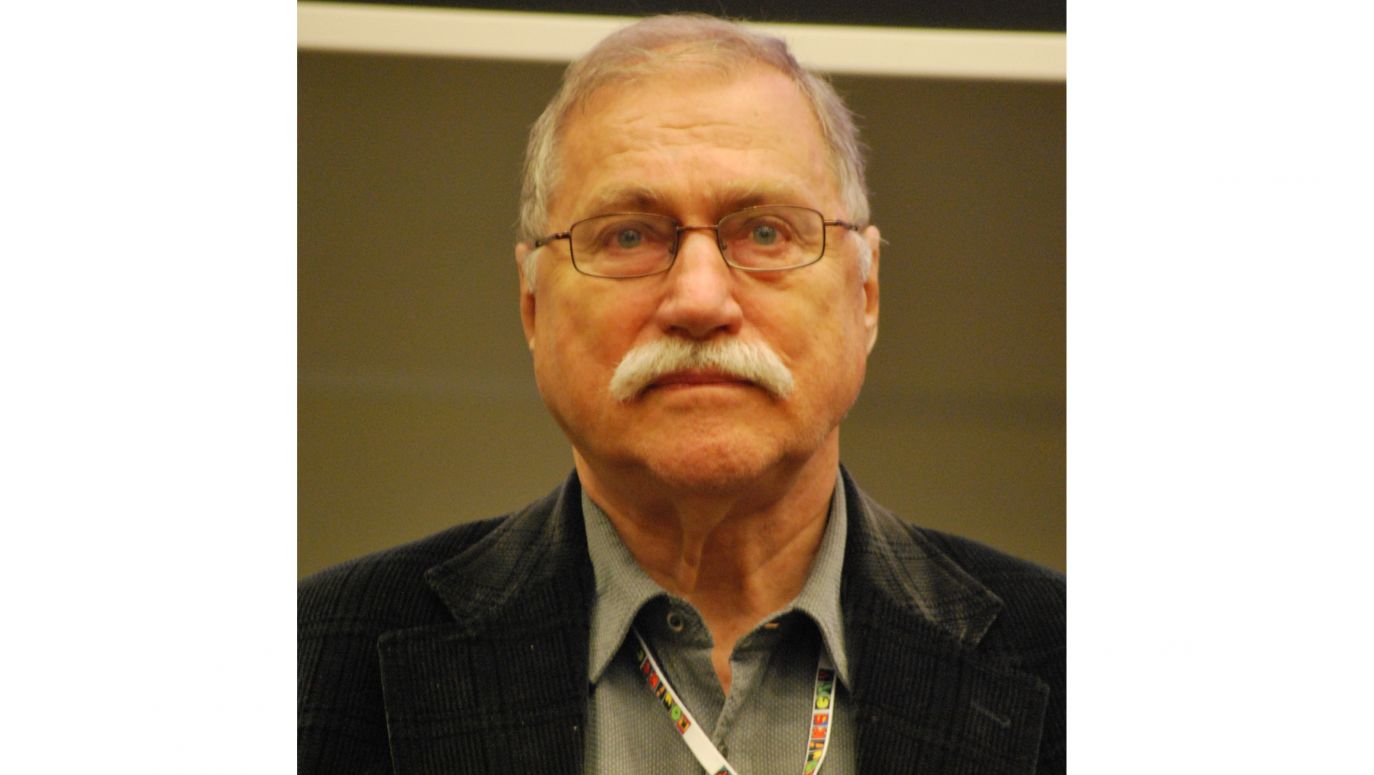

No, his biography is not marked by libertinism or radical turns. Above all, as it is very characteristic of Lech Jęczmyk, modesty would never allow him (as happened to so many others) to make of his life either a monument to be worshiped at or a whip for those who think differently.

Nearly every recallection about him touches on his childhood in Bydgoszcz, and then wartime Warsaw where the Germans relocated his family to, and how after being blacklisted in the early 1950s [by the communist government] he failed to get accepted and pursue his dream of studying English philology. Instead, he read Russian studies, significantly sharing this experience with such later writers as Janusz Szpotański or Andrzej Walicki, who also managed to survive the worst years of Stalinism studying at what would appear to have been be the most ideologically rigid department [of the University of Warsaw]. It seems unlikely that Jęczmyk harbored any illusions at that time. His brother Janusz (1938-2008), a poet and translator of poems (including bitter rhymes in Vonnegut's novels translated by Lech) was arrested in October 1957 during a demonstration in defense of the "Po Prostu" [the independent literary weekly], which Gomułka [Poland's communist leader between 1956 and 1970] closed down.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Lech Jęczmyk began his career as a translator and editor at the "Iskry" ["Sparks"] publishing house, collaborated with the student weekly "Itd" ["ETC"], and worked briefly at the Institute of International Affairs. He made a name for himself at the "PIW" ["National Publishing Institute"] after offering his services to translate works by Heller and Vonnegut as well as Ken Kesey's "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest". (It was years before Kesey's equally anarchistic and non-God-fearing novel was eventually translated into Polish by Tomasz Mirkowicz.) As Janusz L. Wiśniewski [the Polish scientist and writer] recalls, the Heller and Vonnegut books reached Jęczmyk through Robert Gamble, whom he had met during a "behind the Iron Curtain" trip by Harvard students from the US to Poland in 1958. Gamble was to remain involved with Poland for many years, establishing the "Media Rodzina" ["Media Family"] Publishing House in the Third Polish Republic.

Habent sua fata libelli.

Dream about publishing house

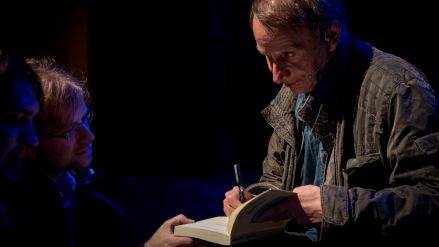

Jęczmyk had little chance of establishing a publishing house in the People's Republic of Poland, despite his great desire to do so. In "Iskry" ["Sparks"], he created the legendary sci-fi anthology series "Kroki w nieznane" ["Steps into the Unknown", 1970-1976], his ambition being to turn the series into a monthly. However, this was not to be achieved until ten years later, when he co-founded "Fantastyka", a monthly sci-fi magazine, whose foreign department he initially headed before becoming the head of publication in 1990, a position he held for three years. Meantime, on orders of the Central Committee of the Communist Party's Department of Culture, he was dismissed from "Iskry". He then found a job managing the English-language literature department of the "Czytelnik" ["Reader"] Publishing House.

As the publisher of "Kroki...", then with "Czytelnik as with "Fantastyka", Jeczmyk was involved in printing both foreign writers (Dick, Harry Max Harrison) as well as Polish authors (Maciej Parowski, Janusz Zajdel and Marek Oramus) and so was actually co-creating the genre of "sociological fantasy" that, inspired by George Orwell and Aldous Huxley, was attempting to describe contemporary societies through the medium of science fiction. Literary circles repaid him in a special way: Maciej Parowski, creator of today's renowned Polish sci-fi comic "Funky Koval", is responsible for the character of Paul Barley, Funky's boss and friend, who is based on Jęczmyk. Barley, undefeated in the martial arts (and drinking), is a member of the DB4 expedition, while on Earth he is the president of the "Universs" detective agency.

The description of Barley is not accidental. Jęczmyk trained at judo from the time he was in high school. In 1967, he was a medalist at the Polish Championships and he remained a member of the national judo team until 1969, one of the first in Poland to achieve 1st dan status, judo's highest ranking. He became an active member of the Church of St. Stanisław Kostka [the Warsaw church known for its religious-patriotic sermons in the 1980s] because of his skills as much as his membership of the Solidarity Movement and his involvement with the Pastoral Care of the Creative Circles. He did not wear a linen forage cap or, and if he did, it was for disguise and camouflage. He was actually the head of the group protecting Father Jerzy Popiełuszko [the Catholic priest associated with Solidarity who was murdered by the Secret Service in 1984]. Who knows what would have happened had he accompanied Fr. Jerzy to Bydgoszcz on October 19, 1984?

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE