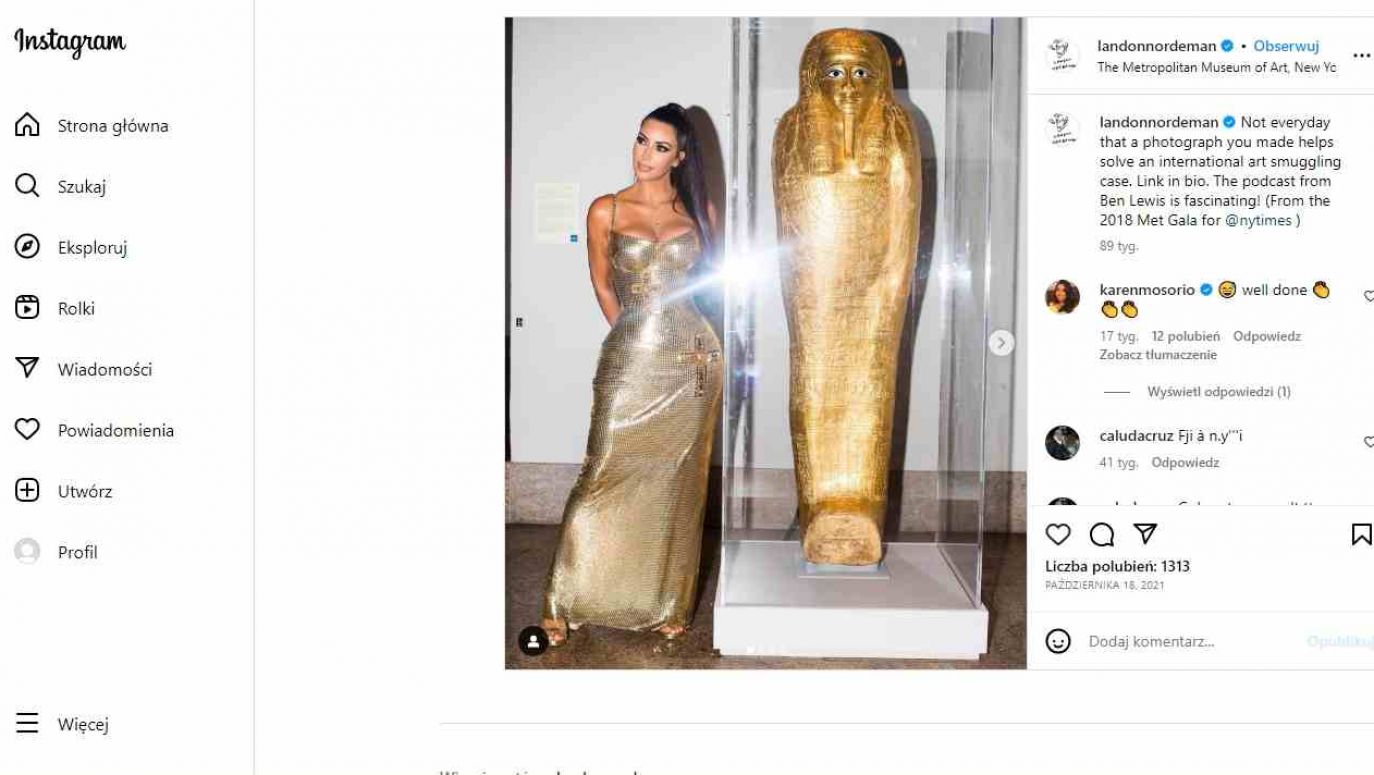

How Kardashian helped smash antiquities gang

12.07.2023

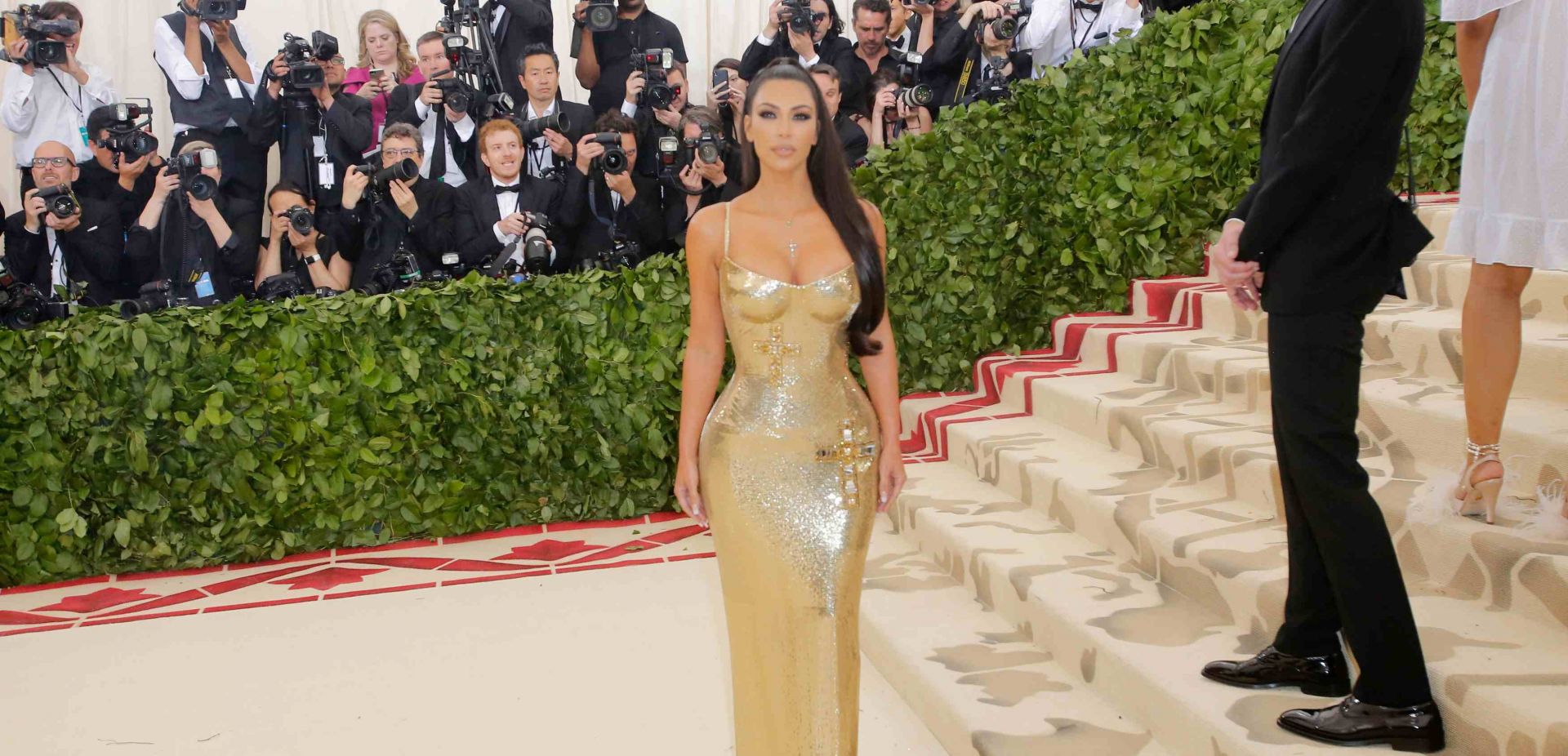

It all started with the New York Met Gala held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2018. The symbol of the event became a photo of the celebrity Kim Kardashian standing next to a golden sarcophagus – a 2,000-year-old golden coffin of the priest Nedjemankh worth $4 million.

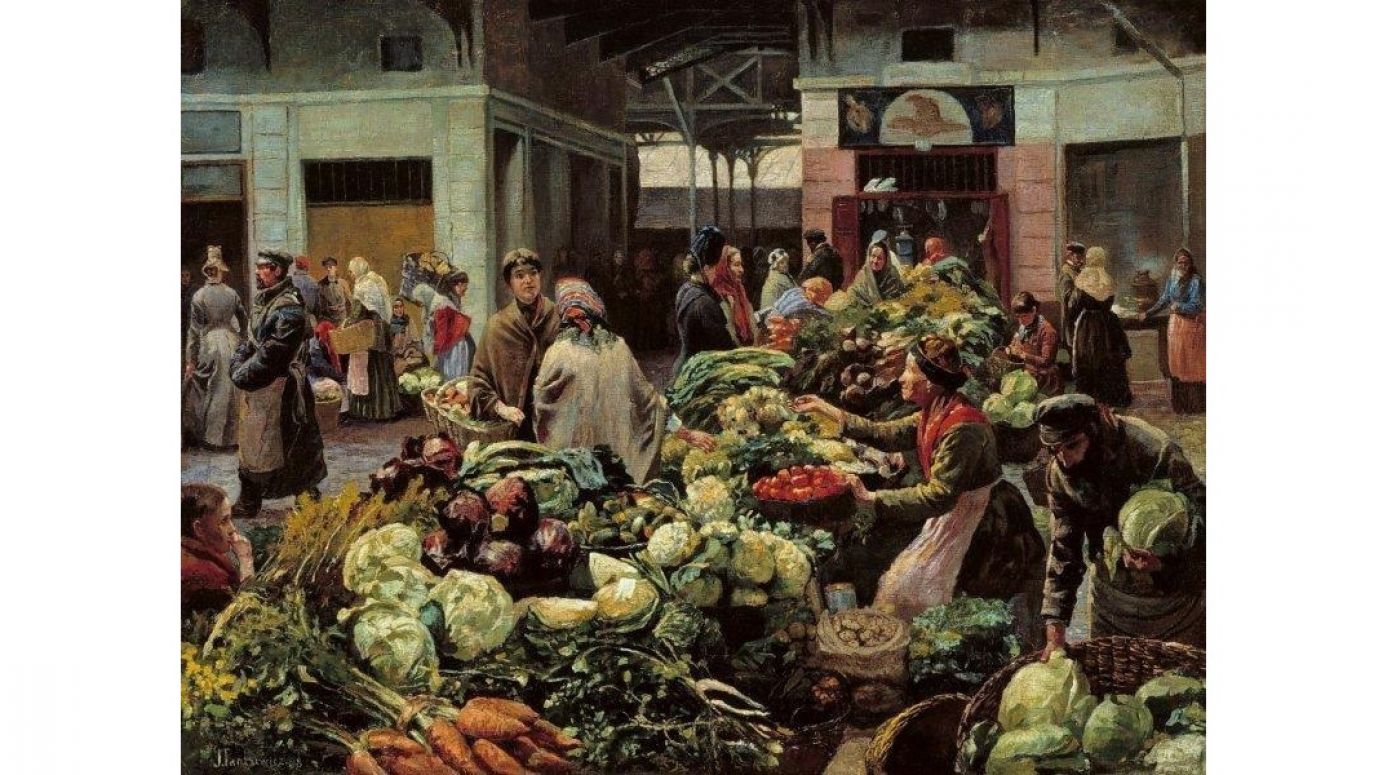

The visual and technical analysis of the painting only increased the doubts: fluorescent photographs and X-rays suggested that the differences were not the result of conservation work. The painting acquired by the museum also has different dimensions from the one painted in 1888. The differences can be multiplied. It can therefore be assumed that the “Vegetable Market” in Poznań is a signed copy of an authentic painting by Józef Pankiewicz.

Fake Axentowiczs

Since the 19th century, many forgeries have been circulating on the Polish market. The production of “falses” results from a boom in art, caused by the development of museums, private collections and the depreciation of the rouble. Wealthy, though often ignorant of art, Varsovians invested in well-known names – Axentowicz, Brandt, Kossaks, and also Pankiewicz. It happened that they bought “Axentowiczs” produced, for example, in the Polish Picture Factory, which released forgeries of works created in the 19th and 20th centuries. Fake paintings also came to Poland from Berlin or Munich.

The boom continued during WWII. In occupied Warsaw, there were many well-stocked antiquarian shops, not only with paintings, but also gold, silver and porcelain works of art. Thinking about their future after the war, Poles got rid of occupation banknotes and invested in valuable art objects. Not always authentic. Art historians from the National Museum in Warsaw, with the approval of prof. Stanisław Lorentz as experts in art salons, tried to combat this phenomenon by conducting an inventory of valuable paintings and eliminating “falses”.

How many of the paintings looted during WWII could have passed through reputable auction houses?

see more

After the end of WWII, the situation only worsened. The black market flourished, with objects from the western and northern areas, as well as from Germany (sold by the Soviets and looters). Not only “Axentowiczs” were popping up, but also “Bruegels” and “Dürers”. Paintings and silverware were forged with the use of special stamps to engrave the maker’s mark. There were also signed copies. One of such copies may be the “Vegetable Market”.

It should be emphasised, however, that contemporary provenance research significantly exceeds the level of the 1948 report. Moreover, the Greater Poland Museum acquired the work in good faith, under very unfavourable circumstances: there was gigantic chaos caused by both the war and the establishment of communism. The then management had nothing to do with the current staff of the National Museum in Poznań.

However, this does not change the fact that it is worth asking the question: if the “Vegetable Market” from the MNP is a copy, then where is the original? For now, it remains unanswered, and the painting has undergone very meticulous conservation by the MNP. However, if the thesis of Prof. Haake will be confirmed – and everything seems to indicate that – the work should be included in the official lists of stolen and exported monuments.

Quite a modern saint

The purchase of a signed copy didn’t happen only to this museum. The directors of many foreign galleries can be accused of a lack of criticism and a desire to enrich their collections. Examples include Shermen Emery Lee, director of the Cleveland Museum of Art, and Prince Badr of Saudi Arabia.

In 1973, the Cleveland Museum bought part of an altarpiece triptych attributed to Matthias Grünewald (actually Mathis Nithart) for around two million dollars from the Frederick Mont Gallery in New York. He depicted St. Catherine of Alexandria. At the time of purchase, director Lee described the work as “a beautiful, mysterious painting of great historical importance”. And this despite the fact that Joachim von Sandrart, an art theoretician, author of the source study on the history of German art “Teutsche Academie der Edlen Bau-, Bild- und Mahlerey-Künste” stated that this triptych does not exist: during the Thirty Years’ War it was plundered by the Swedes and loaded onto a ship that sank.

Five years later, the famous German journalist Reinhard Müller-Mehlis revealed that Frederick Monte had bought St Catherine from the renowned Oskar Scheidwimmer gallery in Munich. The art dealer was to buy it from a private person who inherited the painting from a deceased aunt owning a castle in Alsace. Meanwhile, the journalist discovered that in fact “St. Catherine” was painted by a little-known contemporary painter Christian Goller. He even interviewed him.

The artist declared that he had painted nearly a hundred paintings “in the type” of the originals. He did not consider himself a forger. He did not intend to sell his works as genuine. He painted purely for satisfaction.

Nevertheless, the American museum had quite a problem.

The same problem is faced today by the Saudi prince and minister of culture Badr bin Abdullah, who in 2017 auctioned off the “Salvator Mundi”, attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, for $450 million at the Christie Gallery in New York. And in this case, the story of the picture resembles a racial thriller and has been filmed.

Museum made of sand and fog

Leonardo completed the “Salvator Mundi” in 1513. King Louis XII of France became its owner. The painting passed through many hands, but was finally declared lost. Suddenly it popped up. In the UK. In 1958 it was sold at Sotheby’s for £45.

Already in the 21st century, the American art dealer Robert Simon became interested in it. He spotted it at an auction in a small New Orleans salon. He bought it and one evening brought the painting, wrapped in a plastic garbage bag, to friendly restorers Diana and Mario Modestini. The couple recognised the work as a painting by one of Leonardo’s pupils and undertook to restore it. After the restoration, the object was presented to many experts who came to the conclusion that it was a lost painting by Leonardo da Vinci (although there were doubts about the author, it was suspected that it was painted by Giovanni Boltraffio, an artist’s pupil). In 2011, it was exhibited at the National Gallery in London at the exhibition “Leonardo da Vinci – Painter at the Court of Milan”.

A few years later, the “Salvator Mundi” was bought by the Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev. The billionaire – who broke off relations with the Kremlin and now supports Ukrainian civilians – decided to diversify his investment portfolio: he bought the AS Monaco football club, a mansion in Florida and – with the help of the Swiss art dealer Yves Bouvier - 38 paintings for a total of $2 billion, including works by Leonardo, René Magritte, Gustav Klimt and Amadeo Modigliani.

In 2017, the billionaire sold the “Salvator” with the help of the New York auction house Christie’s. The work was subjected to extraordinary marketing efforts. Leonardo was created by Christie as a “brand”, an artist of all time not subject to any classification. And the painting itself was presented as “The Last Leonardo”, the only one remaining in private hands (in fact, the “Madonna of the Yarnwinder”, the property of the Duke of Buccleuch, also remains in private hands). There was also no mention of doubts as to the authorship of the work.

After a fierce telephone auction, the painting sold for $450 million. The identity of the buyer was to remain anonymous. The New York Times, however, quickly discovered that the buyer was the Saudi Prince Badr, a minister and respected investor with numerous interests in real estate, telecommunications and recycling.

In the Polish People’s Republic (Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa – PRL) Orthodox works of art were looted on a massive scale. At least 2500 icons from 15th to 19th centuries were stolen, so was about a dozen or so antique books and prazdniks.

see more

Probably the work of Leonardo da Vinci was bought as part of the transformation of the image of the desert kingdom carried out for several years: from a global supplier of oil to a global centre of culture and tourism. The Saudis, expecting to lose profits from oil due to the transition to modern technologies, are carrying out socio-economic reforms so that the country begins to attract foreign investment and tourists. The conservative, Muslim kingdom introduces laws that equalize the position of women and men: ladies are allowed to run cars and their own businesses, and Saudi princesses are on the covers of foreign fashion magazines. It liberalizes its culture: cinemas opened. And it is investing heavily in the Al-Ula region, for example, which is on the UNESCO World Heritage List. It is located in the historical land of Hijaz, on the Red Sea, on the ancient incense trail. It is considered an open-air museum: there you can admire 111 tombs from the 1st century AD, there are the ruins of the city identified with the biblical Dedan.

One of the areas of investment is the expansion of the hotel network. There is information that a special museum will be created to present the “Saviour of the World” as a major tourist attraction.

A photograph that shook France

The catch is that after the purchase of this painting, doubts about its authenticity returned. In 2018. The Saud family sent it to the Louvre for technical analysis (fluorescence, X-ray, infrared studies). Its authenticity was to be confirmed by Jean-Luc Martinez, the director of the Paris museum at the time. Interestingly, however, the “Saviour of the World” did not appear in the exhibition organised by the Louvre in 2019 to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Florentine’s birth.

Instead, one scandal followed another. First, the Russian oligarch Rybolovlev sued his art dealer Bouvier and the Sotheby’s gallery for alleged price-fixing and overpricing. Then the Prado Museum recognized the “Saviour of the World” as a copy, and in May 2022 Jean-Luc Martinez was arrested for alleged involvement in illegal art trafficking and money laundering. The Paris prosecutor’s office launched an investigation against him for “aiding and abetting gang fraud and concealing the origin of illegally acquired cultural goods”.

The investigation – which shocked France – focused on nine objects bought by the Louvre for 50 million euros, including a pink marble stele engraved with Tutankhamun’s name, which may have been looted from Egypt after the Arab Spring (2010-12). During this period, many antiquities were stolen from the region, stamped with false certificates of authenticity and sold to European galleries, among others. The scandal involves German-Lebanese art dealer Roben Dib, who is suspected of trading in looted antiquities, and respected archaeologist Christopher Kunicki, an antiquities expert accused of criminal conspiracy and money laundering.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

It might have been bought by the famous collector Ignacy Korwin-Milewski. However, it was not presented at collective exhibitions or cross-sectional exhibitions of the artist’s works. The documentation shows that in 1948 it was purchased for the collection of the Greater Poland Museum (now the National Museum in Poznań – MNP) from Wanda Chłapowska. Before that, it had passed through the hands of Jerzy Remer, a monument conservator, and Wincenty Szarkiewicz, an engineer from Kraków.

It might have been bought by the famous collector Ignacy Korwin-Milewski. However, it was not presented at collective exhibitions or cross-sectional exhibitions of the artist’s works. The documentation shows that in 1948 it was purchased for the collection of the Greater Poland Museum (now the National Museum in Poznań – MNP) from Wanda Chłapowska. Before that, it had passed through the hands of Jerzy Remer, a monument conservator, and Wincenty Szarkiewicz, an engineer from Kraków.