The professor was also very patient and calm -- a stoic, you might say. Once a man visited him and as he was leaving the artist gave him one of his works. Nowosielski's wife, Zofia, reproached him, saying: "Jurek, this painting was supposed to be part of your next exhibition. It is already published in the catalog. What are we going to do now?" Nowosielski said nothing. He just locked himself in his study. After a while he came out and in silence handed to his wife an identical painting to the one he had given to his guest. He simply painted it a second time. This, to me, was quite unusual.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

It was only after I got to know him better, that I understood the meaning of his controversial statements. He wanted to shake up dormant feelings and break down stagnant thinking. His aim in making bold statements was to provoke and force others to reflect. He was also a professor at Cracow’s Academy of Fine Arts. The unique way he expressed himself has since served as an example often used in academia as a way of encouraging students to think more broadly and deeply about any given topic.

His way of thinking also stemmed from his deep spirituality.

Faith was important to him throughout his life. He was brought up in a Polish-Ukrainian family. His father, a railway official, was a Uniate from the Lemko region [an ethnographic area in southern Poland traditionally inhabited by the Lemko people]. His mother was Catholic with German roots. Jerzy Nowosielski was baptized in the Greek Catholic Church. Later he had a period of exploration and rebellion. He studied the religions and philosophies of the East and even went through a period of atheism. Ultimately, he consciously decided to accept Orthodoxy, although the Greek Catholic rite remained very close to his heart. However, having studied various ideas and worldviews, he stopped at Orthodoxy and remained with it, having concluded its teachings to be the most valuable. And from that moment on, he never had any doubts about his religion.

His path in Orthodoxy was very stable and clear. His words, published in the book "The Otherness of Orthodoxy", a compilation of his articles, prove it beyond any doubt:

The moment has finally come when I regained my faith. It was not the same faith I inherited from my parents. It was completely different. Preceded by some information and experiences from the occult community. But the moment of re-enlightenment itself seemed to be independent. It was the moment of my re-entry into the Church -- the Orthodox Church.

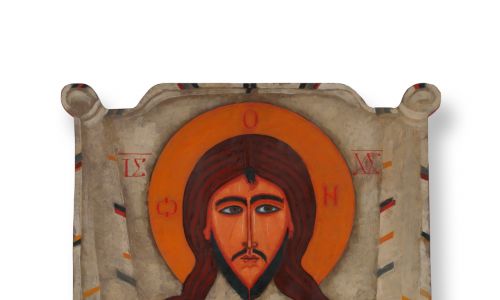

His religious sensitivity was also reflected in his artistic work. He used to say he was not an icon painter, just simply a painter, and yet his sacral works are impressive. Most of the icons in the Orthodox church in Cracow are works by Professor Jerzy Nowosielski. How did so many of his paintings end up in this temple?

This is mainly thanks to Fr. Witold Maksymowicz, who was a parish priest here between 1984 and 2004. He was a great fan of Nowosielski's works. He understood his art, considered it unique and made sure that there was as much of it in this place as possible. It was natural, given that the professor was our parishioner and took part in the services. One of our oldest parishioners, Alla Bałasz, recalls how Jurek (as she would call him) used to spend many hours in the church, praying and looking at the exisiting icons. She remembers how he saw the need to fill some gaps among them, not as an artist, but as a person participating in the everyday life of the parish. Thus, the changes he introduced in the iconography were the result of his deep thoughts and experiences.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE