Archaeoastronomy is not looking for an ancient UFO

22.03.2023

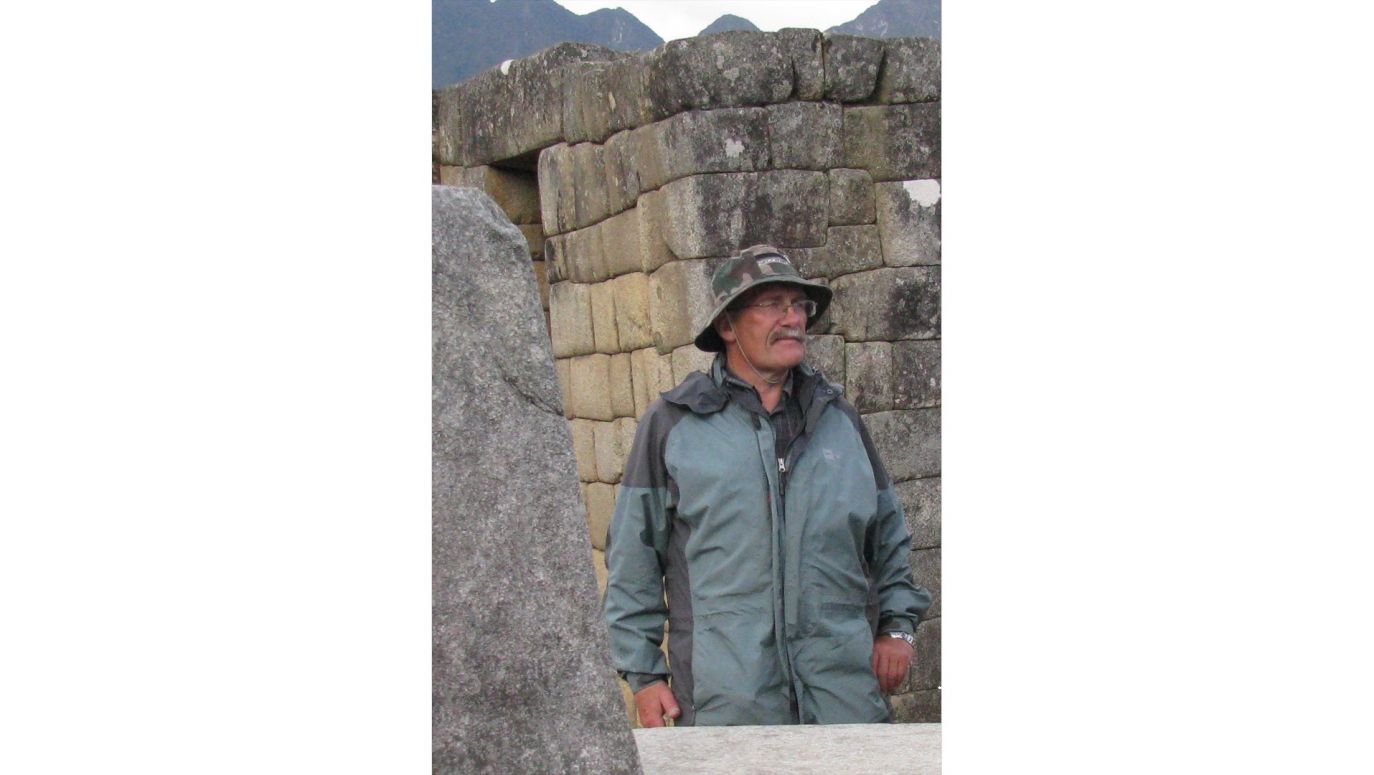

At Machu Picchu, I am involved in astronomy and the Inca calendar. For them, it was a great surprise that Europeans came and made them introduce a seven-day week. They had a completely different form of time organisation before that," says Professor Mariusz Ziółkowski from the University of Warsaw, archaeologist and head of the Andean Research Centre.

The last ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Empire fathered 8 children and died a century ago at the age of less than 35.

see more

A distrust therefore arose towards archaeoastronomy, fortunately later overcome. And it began when, for example, the eminent professional astronomer, founder of the journal 'Nature', Norman Lockyer set about an astronomical analysis of the Egyptian temples and pyramids, and later of the famous Stonehenge, with the very accurate measuring methods available to him at the turn of the 20th century. He attempted to date these monuments on the basis of the difference in the orientation of their major axes and the directions to the sunrise or sunset points in his own time. And he took as a starting point the orientations of the axes measured with a theodolite to the precision of an angular second, although neither the ancient Egyptians nor the creators of Stonehenge had theodolites, as we well know from the whole archaeological context of these cultures! The resolution of the human eye, on the other hand, is several tens of times less, varying between 2 and 3 angular minutes.

Archaeologists caught their heads because the dating proposed by Lockyer , for example in the case of the Egyptian temple at Dendera, was too early by about five thousand years. He did slightly better in the case of Stonehenge (an error of about a thousand years), but this was rather pure coincidence. On the other hand, the German astronomer Rolf Mueller, who used this method and worked in Bolivia in the late 1920s, tried to date the monumental Kalasasaya temple in Tiahuanaco (the one on which the famous Gate of the Sun now stands) and came up with the result that this monument is at least 10 000 years old! In fact, it began to be erected after 500 AD.... For this reason, the method used by Lockyer and his followers is unacceptable.

What, then, does one need to find in order to recognise that a particular culture conducted astronomical observations, for example?

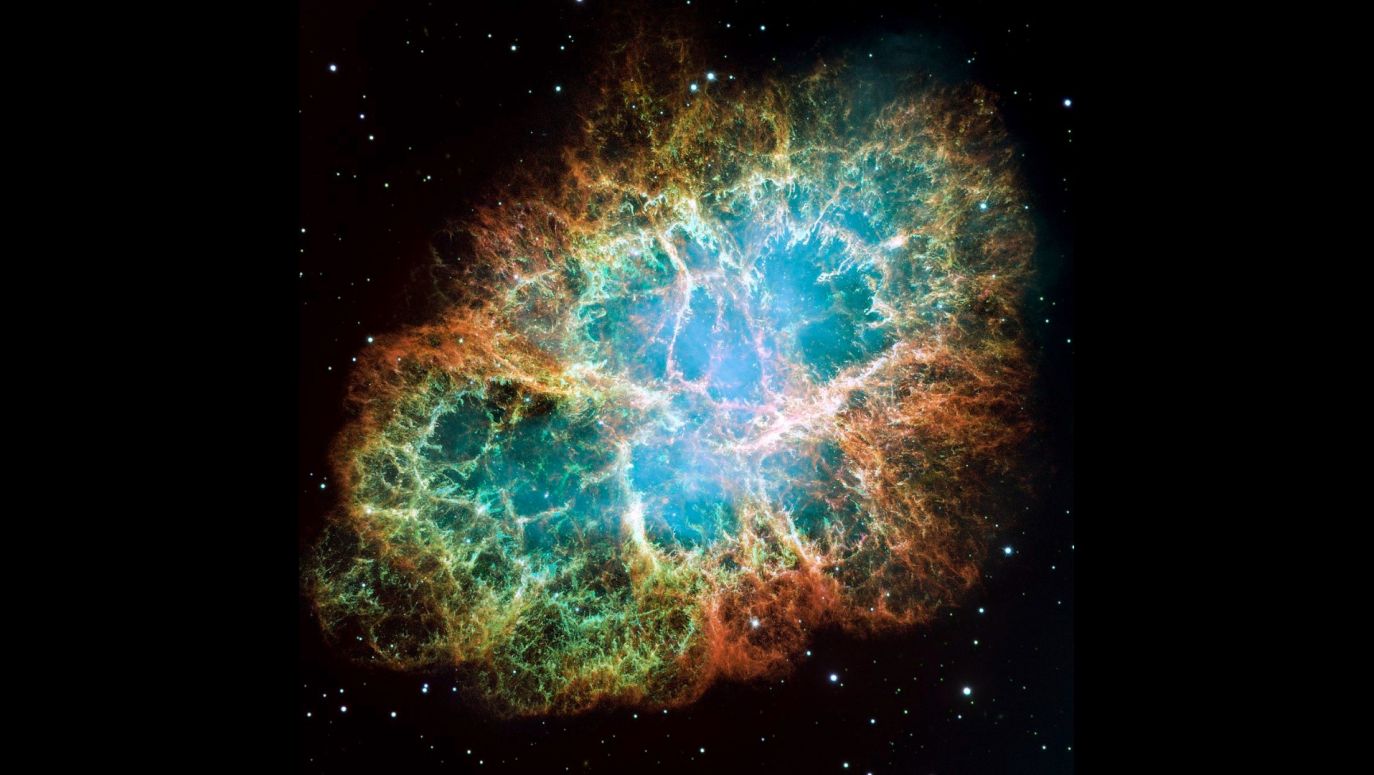

Archaeoastronomy draws on a variety of sources. These include orientations of sacred constructions, ancient texts and works of art. Perhaps not in the simplest way, but in the most appealing manner, they speak, for example, of the decorations in tombs, if only from ancient Egypt or the much later Han Dynasty of China. If they depict stars, the sun, other celestial bodies and are in the form of a dome, the subsequent analysis of such material becomes quite obvious, especially when these cultures have left written sources, later read. Also in the cave art of the US Southwest, such a famous artefact, which immediately forced an astronomical interpretation, is the depiction in the context of the Moon of a supernova explosion in 1054 after Christ. Such a phenomenon must have made a huge impression on the communities of the time.

It is worse with the orientations of buildings, because here the criterion of intentionality is most relevant. And it is not easy to prove that a building was oriented in a given direction so as to allow for a specific, say cyclical observation of some astronomical phenomenon on the horizon. This problem was faced, for example, by British researchers working on so-called megalithic astronomy. They looked for a solution in statistics and found that if more or less the same orientation of the main axis of an assumption is repeated in dozens of objects, it is not a coincidence. And if the cause is not random, then perhaps astronomical? Then it is necessary to reconstruct with mathematical methods why this might have corresponded at the time of the creation of specific objects. For in astronomy, for example, the phenomenon of precession causes the positions of celestial bodies in the sky to change in a cycle lasting 26,700 years. Hence, north was not always indicated by the Pole Star. For the ancient Egyptians, it was indicated, for example, by Thuban, one of the stars of the Dragon constellation, but already in the time of the ancient Greeks, no star was close enough to the pole to be able to determine the directions of the world with precision.

The positions of bodies in the sky are changing. North today is indicated by the Pole Star, in ancient Egypt it was indicated by Thuban of the constellation Dragon, and in the time of the Greeks there was no star to help determine the directions of the world

If a building was deliberately and precisely oriented by its builders, for example, to the place where the sun rose on the winter or summer solstice, it is possible to calculate how much time has passed since the sun rose on that exact point on the horizon during the solstice. The ecliptic, or the plane on which the Earth's orbit lies, is relevant here. Or, more precisely, its change, because the Earth's axis is inclined to the ecliptic at an angle whose value fluctuates over a cycle of 41 000 years. This angle changes from 21.8° to 24,4° (currently stands at 23.4°).

In existing designs, these orientations will always be obtained with some approximation, such as the resolution of the human eye. For astronomers, these are huge differences that result in a large disparity or a large range of potentially correct calculation results. So one would have to assume in advance some data that we do not know: with what accuracy these ancient architects and builders worked. As I mentioned, it was unlikely to be an accuracy comparable to that measurable by us today. And here we come back to Stonehenge: first we need to know the date of the construction of the structure - approximate plus or minus by a hundred or a few hundred years - and then we can check whether, for example, something was visible in the main axis, in the corridor or in some other prominent part of this structure at the time when it was built. On the other hand, it is not permissible, as I said earlier, to do the reverse procedure, i.e. to date an object on the basis of its orientation.

Archaeology is a contextual science, meaning that it requires a holistic view of the totality of the data we have. Just what about those artefacts whose appearance in a particular place and time layer we simply do not grasp?

Context is very important, but it is important to remember that there are things in archaeology today that are popularly referred to as 'black swans'. These are surprises that, at a given historical moment and anthropological-geographical context, should not have occurred, but did. Here, for example, there is an object that completely changed our view of the astronomical knowledge of the ancient Greeks in the Late Classical and Hellenistic period (4th - 1st century BC), namely the Antikythera mechanism. No one expected this, after all, at first the discoverers were hounded that it was not an ancient object at all, but a fragment of some device from the 19th century. Then it turned out beyond doubt that it was authentic. And this undermined everything we had believed until then - not only about the theoretical mathematical knowledge of the ancient Greeks, but above all about their technical and mechanical abilities.

On the other hand, Göbekli tepe and the astronomical knowledge of the 12,000-year-old constructors contained therein does not surprise me. Why? Because another myth, which I fight when I teach archaeoastronomy at the University of Warsaw, claims that the further back in history people were dumber. Just because they didn't have radios or televisions or didn't fly to the moon doesn't mean that when they walked around 20,000 years ago in nicely tailored clothes and shoes and even hairstyles, nevertheless with primitive equipment, they were less intelligent than today's Europeans, Africans, Asians or Americans. Exactly the opposite - back then intelligence was promoted. Because living conditions were difficult (although not as extreme as some imagine). These people also had a great deal of time on their hands. Based on ethnographic analogies from studies of modern hunter-gathering communities, we can safely assume that in the Upper Palaeolithic, it was enough to work 4-5 hours a day to ensure a decent survival. This is considerably less than later agricultural peoples worked.

The idea was to cut off the branches and hold the current together

see more

Therefore, astronomical observations and calendars do not begin at all with the advent of agricultural cultures, but tens of thousands of years earlier. As Chantal Jègues-Wolkiewicz, a French researcher of decorated European cave paintings from that period, has shown, there were groups of them which were chosen for the orientation of the entrance in an astronomically relevant direction, above all for the rising of the Sun on the winter and summer solstices. So the fact that 12,000 years ago in Göbekli tepe the consequence of this accumulated astronomical knowledge was the creation of gigantic objects with astronomical orientations in mind is not at all surprising.

Is there, then, some underlying core of astronomical knowledge that all civilisations described to date had, the existence of which might suggest that these observations were still made in the Palaeolithic? In doing so, I understand, of course, that people in the north and south of our globe see the sky differently starry, however.

Most of our information on the oldest history of Homo sapiens (we are not talking about Neanderthals here) comes from the Northern Hemisphere, although our species appeared much earlier than in Europe, e.g. in Australia - at least 50 000 years ago, or Africa - 200 000 years ago. However, the vast majority of finds interpreted as evidence of calendar and astronomical knowledge, such as cave art or certain types of movable artefacts, are now mainly from Europe and Siberia, much less Australia, southern Africa or, more recently, Indonesia. Thus, any comparative inquiry into the difference in visions of the sky between Palaeolithic cultures of the two hemispheres is rather a song of the future.

Although there must have been differences, because the constellations of the southern sky are completely different from those of the northern sky, and, moreover, there was no counterpart to the Polar Star we know so well, or rather the successive so-called polar stars that change every 26,000 years. For example: today our polar star is the alpha of the Little Bear, but for the ancient Egyptians, builders of the pyramids around 2,700 years before Christ, it was the alpha of the Dragon, or the aforementioned Thuban. To summarise: 20 or 30,000 years ago, people saw not exactly the same sky as we do now, but quite similar. However, even today there are elements in common between the hemispheres as well. The basic reference for time reckoning and spatial orientation, if one excludes the two polar regions, are the cycles of the Sun and Moon. These were and are the basic organisers of our time.

In turn, the oldest observations recorded and now known to us, e.g. in the form of incisions on bones (plates from mammoth blows), concern the phases of the Moon and date from the Upper Palaeolithic. Without attempting to reconstruct the beliefs about this celestial body at that time, a very prosaic and practical reason for this interest in our satellite was also a fact that we forget living in an artificially lit environment: that before the period of 'steam and electricity', it was the Moon that illuminated the night-time darkness, and therefore it was useful to know in advance when the full moon and the new moon would be, and for what part of the night it would be bright.

It can be equally practical to observe the moon-related tides, especially if you are a hunter gatherer and hoping for nutritious shellfish. But let's leave the Palaeolithic and get on with your long-standing research into Inca culture and their astronomy, including the recently completed expedition to Machu Picchu. Is there still anything new to be found there?

Silver and lead were smelted in the area as far back as in the early Middle Ages.

see more

I did not start my research immediately in South America. I worked and still work a bit in Pomerania on the so-called stone circles dating from the period of the wanderings of the Goths (1st to 3rd century AD). I worked there with my colleague, the late astronomer Robert Sadowski, to check the precision of their orientation and whether they were oriented only towards the Sun or also, for example, towards the stars, as postulated by German researchers who saw in these circles monuments of the supposedly great astronomical knowledge of Germanic or even pre-Germanic tribes. It turned out that certain solar orientations, e.g. to the directions of the solstices of the Sun, were probably intentional, while those to the stars were absolutely unprovable.

A plethora of the most bizarre archaeoastronomical or rather paraastronomical "theories" have grown up around the circles. There is even an association, which I will not name, dedicated to the "research" of these circles, creating a whole new set of myths and practices. Such as that the energy in these circles can be recharged - if only with caution, so as not to "overheat" (literally and figuratively) - or that they are objects connected with UFO appearances, etc. Adepts of this new cult gather there for ceremonies during the solstices and equinoxes, and they take their rituals very seriously. I find it extremely amusing that in all these considerations about charging themselves with energy, they forget that all these objects, e.g. in Odry near Czersk in Pomerania or in Kashubian Węsiory near Sulęczyn, were dug up. So what these devotees see is not any monument "intact there for many thousands of years" (although we know that it has been there for less than two thousand), but a reconstruction by archaeologists.

And what we do at Machu Picchu... I do astronomy and the Inca calendar. It was with Robert Sadowski that we reconstructed this calendar, and with the help of Professor Tomasz Bulik from the Astronomical Observatory of the University of Warsaw, we made this reconstruction more precise and described it for the audience most interested, i.e. in Spanish. Understanding a culture without a concept of the time system it operates will clearly be flawed. It is as elementary as it will be for archaeologists of the future to discover why our week had 7 days and not, for example, 10, and why such a division was not observed in China at the same time. For the peoples I study, it came as a great surprise when Europeans arrived and had the seven-day week introduced. They had a completely different form of time organisation before that. How did their division of time affect social behaviour, even collective ceremonies? This is why we reconstruct the calendars of ancient cultures.

Although the consequences of this can be quite unpredictable when such knowledge seeps, in a far-simplified form, into mass culture. Such was the case quite recently when many people believed that the world was to end on 21 December 2012. This was thought to be due to the so-called Mayan long reckoning, according to which that very day marked the end of the era of 13 baktuns, or approximately 5125 years. This gave rise to the creation of extremely box office disaster films, with the famous '2012' at the top of the list.

The attempted Incan reconquest was unsuccessful, not least because a large army led by Manko Inca surrounded Cuzco and... stood down. It waited for the full moon to attack. The Spaniards took advantage of this

I, on the other hand, when I read about Machu Picchu - this essentially residence of the elite, where there was no previous settlement - was interested in this special 'sun stone' or 'astronomical stone'....

This is one of the popular but contemporary myths about Inca archaeoastronomy. You are referring to Intihuatana. This name was first recorded probably in 1842, and not at all in reference to Machu Picchu, which at that time had not yet been rediscovered to the world, but a site in the Urubamba valley. The word means "a place used to bind the sun". In the case of Machu Picchu, it is a worked natural rock, a kind of altar used to make offerings, not to make any astronomical observations. The entire residence served mainly representative and ceremonial purposes, and was inhabited by the priestly elite, among others. On the other hand, there are in Machu Picchu, albeit not in the vicinity of this altar, two observatories that were used for relatively precise studies of the Sun and the Moon. And it was these sites that we explored during our expeditions.

It should be emphasised here that when we talk about astronomical orientation, its purpose is important. For example, the entrance to a ceremonial building was oriented in such a way that the Sun rising on the summer solstice could be seen in it, in order to have a theatrical effect on the participants in a religious ceremony. But this at the planning and construction stage does not, as I mentioned at Stonehenge, require any great precision. What is different is the planning and orientation of the structures, which were in fact intended to serve as astronomical observatories. Here, devising and execution as perfect as possible is required, obviously using techniques within the reach of the given culture. Generally, these are small structures, although there are sometimes huge ones, such as the Uluğ Bega observatory in Samarkand.

One of these observatories at Machu Picchu was already known to science, but we have shown that it was much more complex than previously thought. This is the so-called Intimachay cave, located in an area accessible to tourists. In contrast, the second site we investigated is not accessible to visitors. It is located in a part where you have to force your way in with machetes, and where excavations are still taking place. Our Peruvian colleagues, including its discoverer Fernando Astete Victoria, suspected that this site - called Inkaraqay - was used for astronomical observations. However, this still had to be demonstrated, i.e. measured. We did this together with Professor Jacek Kościuk from the Wrocław University of Technology. Everything that is currently known about Machu Picchu, including the astronomical orientations of some of the buildings, not only Intimachay and Inkaraqay, is available online in the form of a synthetic summary entitled "Machu Picchu in context"edited by myself, Proffessor Nicola Masini and José Bastante.

How this sky was once observed is one issue. The second, and even more engaging, is how astronomy shaped the life and functioning of the Incas of the time.

The basic thing: in the modern era, we Europeans are used to the separation of science and religion. However, it did not exist in the Inca community, there were no astronomers who were not priests, so all their activities were linked to the religious system of the society.

Professor Mariusz Ziółkowski studied Mediterranean archaeology and history of art at the University of Warsaw. He currently holds the position of director of the Centre for Andean Research at the University of Warsaw and is also president of the Polish branch of The Explorers Club. He has participated in research projects in Poland, Iraq and, since 1978, in countries of the Andean area: Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia and Chile. He specialises in absolute dating techniques in archaeology, archaeoastronomy and ethnohistory, particularly in relation to Tahuantinsuyu, the Inca state. He is the author and co-author of dozens of scientific articles and books, including 'Machu Picchu in context', a collective work published in 2022 dedicated to the work of the international team he led at the Machu Picchu Archaeological Park. In recognition of his services to Peruvian archaeology, he was awarded an honorary professorship at the Catholic University of Santa María in Arequipa and the Peruvian Order of Merit.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Probably also today - whoever knew the details of the horoscope set for the Year of the Rabbit to the Chinese Communist Party authorities would probably be smarter than the legendary diplomat Henry Kissinger... But let us return to the past and archaeoastronomy. How do archaeologists interact with astronomers, as it seems necessary?

Probably also today - whoever knew the details of the horoscope set for the Year of the Rabbit to the Chinese Communist Party authorities would probably be smarter than the legendary diplomat Henry Kissinger... But let us return to the past and archaeoastronomy. How do archaeologists interact with astronomers, as it seems necessary?