So what is new about the research work from Cambridge and Rehovot that it stormed through the scientific media?

True success is the cultivation - longer than ever before – of the mouse embryos and following observation of embryonic processes, such as the formation of the nervous system or the heart. Previously, we could not observe them

in vitro, so we were unable to study them in detail.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Moreover, until recently, mouse embryos or embryoids have been successfully maintained in culture only up to the sixth or seventh day of development. And the work we are talking about lasts already eight days and a half. The difference seems small, but scientifically speaking, that is very important.

Indeed - after all, the mouse's pregnancy lasts up to 20 days, so - if we try hard enough - we may reach halfway in the incubator.

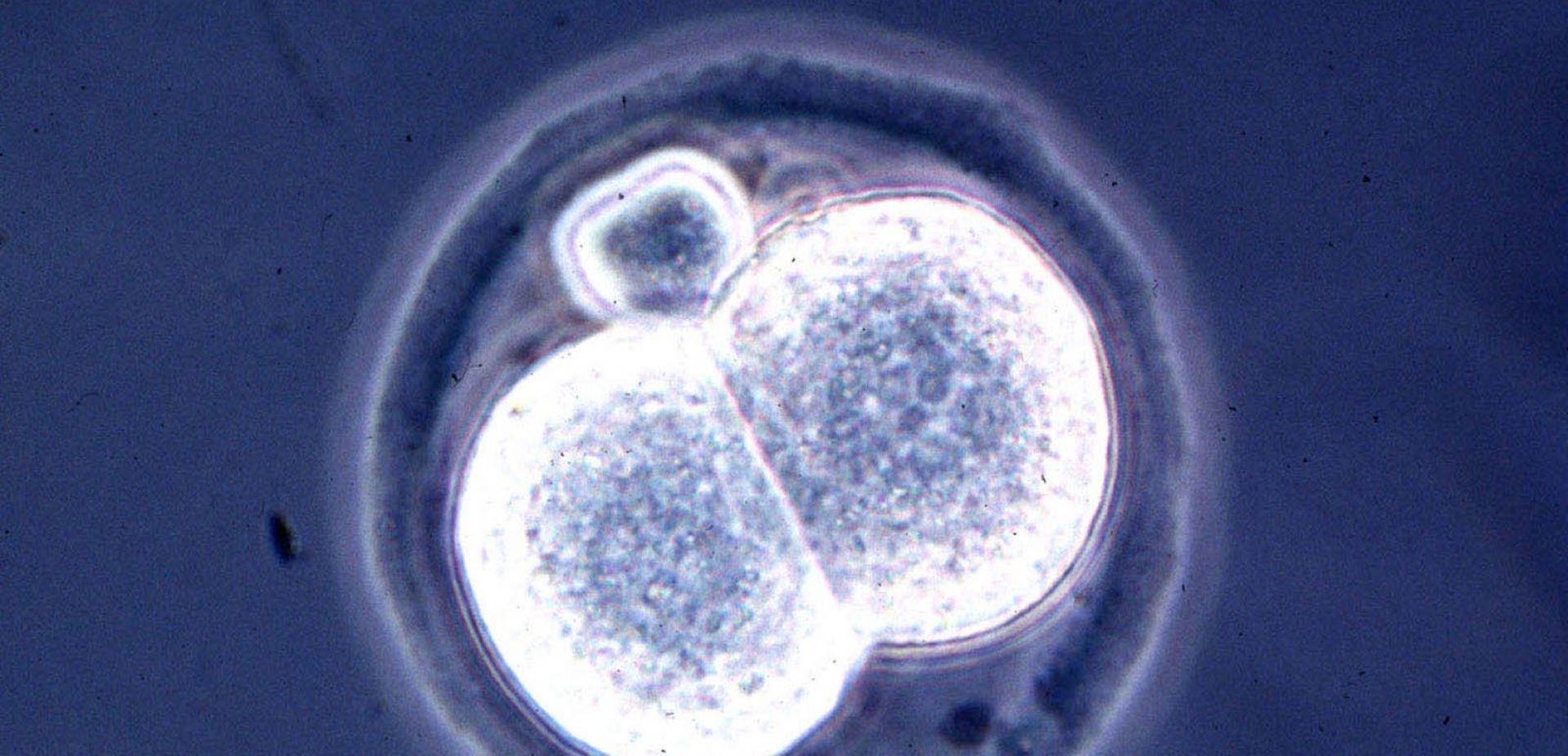

Here, it turned out to be essential to combine stem cells capable of producing an embryo body with those capable of producing extra-embryonic structures. Moreover, the cells that create them provide numerous signals that act as signposts, telling the cells of the embryo where to locate so that the embryo knows, for example, where to find its front or back.

In this phase of development, cells not only divide intensively (which is why the embryo grows) and differentiate (thanks to which many different tissues are formed), but they also move en masse to find the right place.

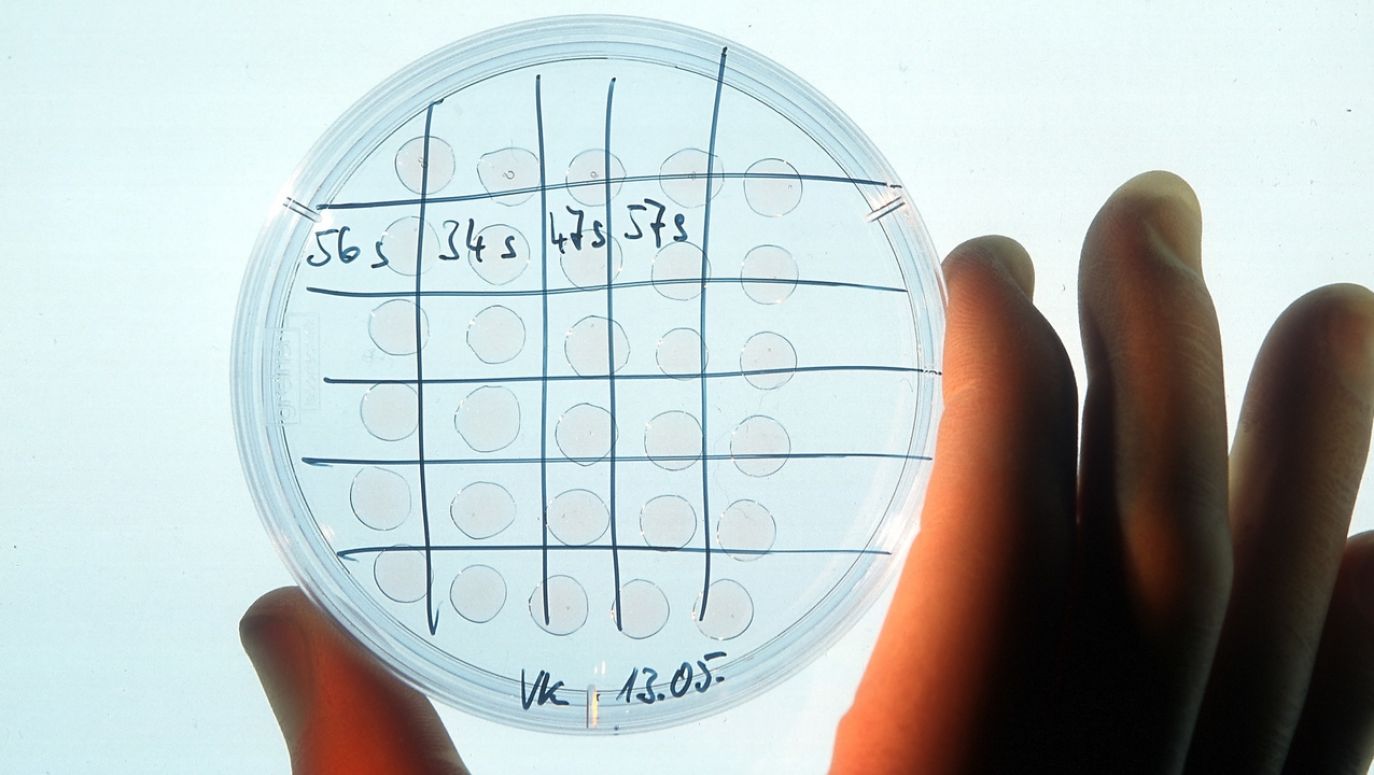

The second technical innovation is a special incubator from the Weizmann Institute.

Normally, the development of such embryos occurs in the womb, so to study them, these must be collected from animals. Embryoids allow research to be carried out without sacrificing pregnant laboratory animals. However, to grow both – the natural embryos and embryoids - a special incubator is required in which the tubes containing the embryos are rotated to allow mixing and oxygenation of the culture medium. This is necessary because - compared to classical tissue cultures that are plated - these embryos are massive and fast-growing structures.

So, is this some kind of an "artificial uterus" that can keep embryos beyond the stage of organ formation? Could it be applied to humans?

It is much easier to conduct such experiments on mouse embryos, where the development is very fast and the embryo size is small compared to humans. Let's imagine this: we start with single-cell embryos, which in humans and mice are of a similar size, and we end with new-borns, one of which - the human one - could easily hold the other in the palm of his hand. In addition, the human embryo takes more than ten times longer to develop than the mouse. Thus, the developmental processes we can already observe in mice today - in laboratory conditions - are still difficult to notice in humans. This technical challenge is still difficult to overcome today.

Can embryos develop into an adult being?

NO. Even if we wanted to, we are currently unable to complete their development.

Ok.. Not within this 'artificial rotating uterus'. What if they were implanted in real wombs?

We can't implant them. For a simple reason - the moment for implantation is strictly defined and very short in the whole process of evolution. Additionally, embryoids are unable to settle themselves properly in the uterus, even if their development is stopped at an earlier stage, where the natural embryo usually gets installed in the womb; Although – roughly or even with the eye armed with a solid microscope and molecular analysis techniques, embryoids only resemble the natural ones, those resulting from fertilisation. They are similar, but they are different. The devil is in the details.

In addition - in its recommendations - the scientific community and the law prohibit any transplantation of artificial embryos into the human womb and human embryos into the uterus of other mammals.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE