In multi-ethnic and multi-religious Poland it was the other way around - it was tolerance that united the nobility against the king. At the time of the Warsaw Confederation, the establishment of a republican system with an elected king - something like today's president - had just begun and religious feuds would have worked against the political unity of the nobility.

A similar system to that of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, with a ruler (Staathouder) subordinate to parliament, was established in the Netherlands, but there the struggle of the followers of the various Christian denominations was important in establishing the principles of the system.

Dynastic marriages brought the Netherlands under the rule of the Spanish Habsburgs, maintaining autonomy. In 1566, the Calvinist North rose up against Spanish domination. The Protestants revolted against the ruling Catholics, and the mostly Catholic southern provinces joined the revolt.

The situation was exacerbated by the slaughters practised in the North by the Spanish expeditionary corps. The Northern provinces dethroned Philip II and declared themselves the Republic of the United Provinces with the position of Staathouder inherited in the Orange dynasty. The South came to terms with the Spanish court.

The reasons for the war in the Netherlands were also purely and classically political, the Spaniards were foreign here with all the consequences of that, and the Netherlands was rich and there was something to grab. However, the religious differences of the two main warring parties added fuel to the fire and motivated perseverance and valour. The rebellious North is today's Netherlands and the South is now Belgium.

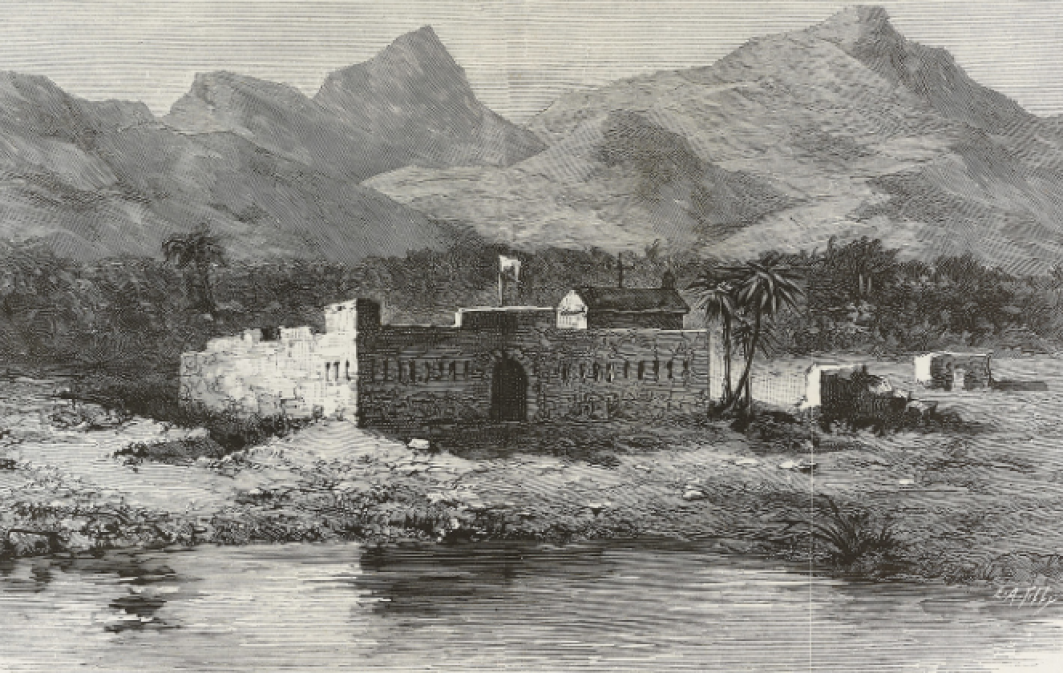

At the aforementioned coastal fortress of La Rochelle, Elizabeth I, Queen of England, sent ships to the aid of the Huguenots. She was the head of the Church of England, separated from Rome, and helped all Protestants on the Continent. Domestically, she fostered an atmosphere of threat of Catholic conspiracies to bring an invasion of the Isles by the 'Papists' and when the Spanish Grand Armada actually set sail for England, it had the feel of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Once the Spanish ships were repulsed, the real threat was over, which did not mean that the fining, imprisonment and beheading of Catholics in the Isles stopped.

The Church of England pronounced obedience to the Pope because Henry VIII had to change several wives while waiting for a male heir, and Rome did not recognise divorce. Under Henry VIII, the Church of England separated administratively; doctrinal differences came later. Under his successor Edward VI, persecution of the hierarchy and the faithful began. They affected the elite, while the country remained Catholic, which in Queen Mary, Edward's successor, gave rise to hopes of re-catholicising the country. The nickname 'Bloody Mary' given to the Queen by her contemporaries says everything about her methods.

Queen Mary's six-year reign was followed by her half-sister, Elizabeth I. She reigned for forty years and proceeded consistently to destroy Catholicism. Attendance at Sunday mass in Anglican churches became compulsory. Catholic worship was initially allowed in the home, later prosecuted. Anglicanism's victory over Catholicism was aided by an army of denunciators, with casualties numbering in the tens of thousands.

William Shakespeare was a Catholic, or rather a crypto-Catholic, and when he wrote in Hamlet that "Denmark is a prison" he had a very different country in mind. The suffocating atmosphere of confinement experienced by Hamlet was the author's everyday reality. The yearning for the freedom of England's eternal religion has been found by modern scholars in Shakespeare's other plays as well. They point to verse fragments of traditional songs, especially mournful ones and Catholic psalms only slightly camouflaged.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Shakespeare was careful in his writing. Privately, he had acquired a house in London with many secret passages and hiding places for Catholic priests. He lived out his days in peace, probably helped by connections in the highest circles and sheer luck. Other writers, such as the Polish - to keep things in proportion - Jan Kochanowski and Mikołaj Rej did not have to camouflage anything.

A Catholic, Kochanowski frequented the courts of Protestant magnates, sometimes accepting various functions, which did not undermine his position at the court of the Catholic king. A less politically active outspoken Protestant, Rej was, however, a member of parliament and a court advocate, and the Catholic magnates received him at home. In Elizabeth I's England, such things were unimaginable.

In the UK, many sentiments, let alone institutions, last a puzzlingly long time. The recent British Prime Minister Tony Blair announced that he had converted to Catholicism, but this only happened after he had left the office. Had he done so earlier, and it was an open secret that he had such inclinations, Britain would probably have sunk. And seriously, there would have been a constitutional crisis, because in Britain, it is the king, or in practice the prime minister, who appoints the bishops. The nation wouldn't put up with a Catholic doing it, quite different if it was a Hindu.

"Papists" returned to the UK Parliament in 1829 and in 1850 the hierarchy of the Catholic Church was allowed to be restored. From the time of Elizabeth I, English Catholicism disappeared from public life becoming a private religion for almost three centuries.

The Protestant English colonies in North America took over from the metropolis the notion that a Catholic was a potential traitor, and the United States that emerged from them did not get rid of this fear for a long time. When a Catholic became president there for the first time in the 1960s, it was widely regarded as an epochal breakthrough.

Polish witches were burned under German codes. Fortunately, religious wars were not imported from the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, which even before the Thirty Years' War had resulted in more than a hundred thousand victims.

Lutheranism was spreading rapidly in Germany and, in addition to the Peasants' War, suppressed by the feudals of both denominations, gave ideological fuel to the Schmalkadic War. The war erupted when some of the Lutheran princes and cities refused to return the just-secularised church estates to the emperor.

Only the Austrian states and Bavaria remained Catholic under the sceptre of the Catholic emperor, so war was inevitable. The Emperor Charles V did not recoil as he wished and had to agree to the Peace of Augsburg in1555. The principle adopted there, "cuius regio, eius religio" (whose land, his religion), remained in force in the Reich for centuries. Anyone who was of a different religion to the sovereign had two years to sell his property and move to another sovereign. The most famous resettler was Friedrich Schiller - much later, during the Enlightenment.

The Warsaw Confederation had no implementing provisions and, from its general terms, those who deny Polish tolerance may conclude that there was some reflection of the principle - whose land, his religion. Yes, there was a way for the lord to judge the peasants according to the principles he professed. There was no encouragement of conversions. Let alone the conversion of free citizens, i.e. the nobility.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Shakespeare was careful in his writing. Privately, he had acquired a house in London with many secret passages and hiding places for Catholic priests. He lived out his days in peace, probably helped by connections in the highest circles and sheer luck. Other writers, such as the Polish - to keep things in proportion - Jan Kochanowski and Mikołaj Rej did not have to camouflage anything.

Shakespeare was careful in his writing. Privately, he had acquired a house in London with many secret passages and hiding places for Catholic priests. He lived out his days in peace, probably helped by connections in the highest circles and sheer luck. Other writers, such as the Polish - to keep things in proportion - Jan Kochanowski and Mikołaj Rej did not have to camouflage anything.