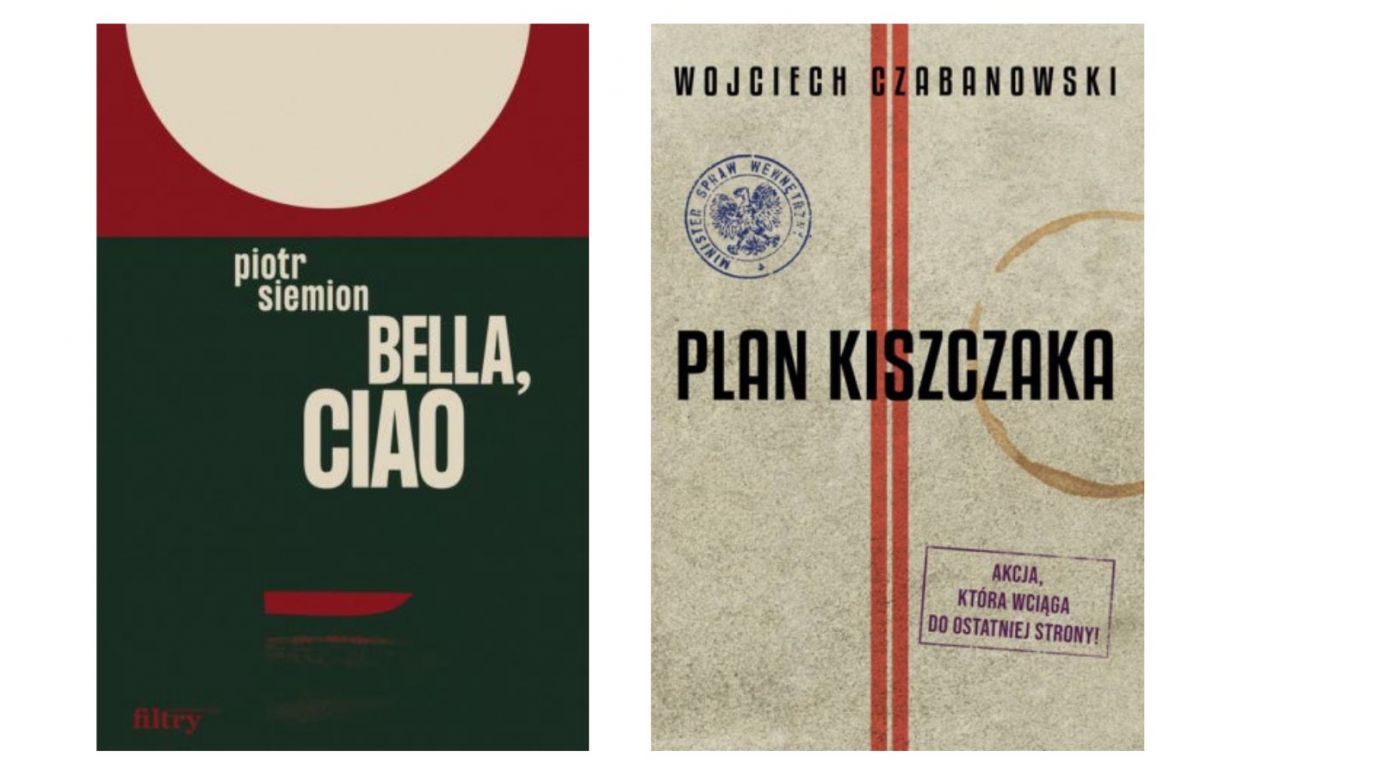

The first of these books is 'Bella, ciao' by Piotr Siemion (Filtry, 2022), the second is "The Kiszczak Plan" by Wojciech Czabanowski (Novae Res, 2022). One and the other I have to summarise and spoiler a tad, which is forgivable insofar as 'Bella, ciao' was published in the spring, so everyone has already had time to discuss it, or at least rehash it, while 'The Kiszczak Plan', still warm (December) abounds with announcements of plot twists and its synopsis already on the wings and the last page of the cover.

"Bella, ciao" deals with a few days of spring after a long, devastating and displacing millions war. We are in the post-German Western Territories, we have an exile of refugees from the interior of the country, an army that supposedly collaborates with and is subordinate to the Soviets, although it secretly hates them, and a group of "steadfast" people who do not have to hide their hatred, but have to hide themselves if they want to break through to the West.

Except that the West is virtually non-existent, there are no man's lands and Soviet army transports, merciless in drinking, raping and stealing. This could have been 1945, it could have been some kind of prose by Konwicki or Mrożek's 'On Foot', 'The First Day of Freedom' or 'Law and Fist' - if it weren't for the suggestion of a recent nuclear bomb strike (which the Soviets didn't have in '45, however) and other clues showing that this is not a simple remake of 1945, but rather another instalment of the same tragedy.

"The Kiszczak Plan" is a marvellous folly, a reversal of all sanctities and signs as if in a carnival costume parade, with a donkey baring his ears from under the bishop's tiara that has been planted on him: Suffice it to say that the story begins with Wojciech Jaruzelski's declaration of war against the Soviet Union on 13 December 1981... - and then picks up steam as the scene of action (and the theatre of battle) shifts to Volhynia and near Kiev, and the survivors of the 'steadfast' from the war years, Solidarity, the CIA and the UPA join the struggle.

Where is the 'eternal Polishness'?

A murderous cocktail, like a "white bear" (dry sparkling wine into which a glass of well-chilled spirit has been poured) - and in Siemion's case it's the same, only better bittered and less concentrated, so that first the legs are taken off, then the consciousness. But both novels play on our most aching historical memory, our most vivid identifications (we of the Steadfast, we of the Home Army, we of Solidarity and the underground) and - THROUGH THEM.

In both novels (sorry, this is the last spoiler), the quasi-steadfast and quasi-soldiers of People's Poland, Kiszczak's militiamen and the zealots from the Podkarpacie region - in a situation where the world is standing on its head and the magnetic poles are shifting - finally join forces, rejecting their quasi-party, or at any rate political, identifications in favour of a Polish cause older (and bigger) than any organisation, however close.

If this is not an expression of the fatal weariness of Poland's stagnation in two hostile trenches, a longing for what the Jagiellonian Club a few years ago called an 'inclusive Polishness', polyphonic, unifying and bonding - then I don't know what other signal readers would need to notice this longing.

– Wojciech Stanisławski

-Translated by Tomasz Krzyżanowski

TVP WEEKLY. Editorial team and jornalists

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

The language that governs us

The language that governs us