It is something worse than the loss of troops and battleships, “than financial bankruptcy or the invasion of one’s territory”, it is “the abandonment of tradition and the loss of an ideal. The history of all peoples confirms this” (Delassus wrote these words in the first decade of the 20th Century).

The German orchestra played the Polish national anthem…

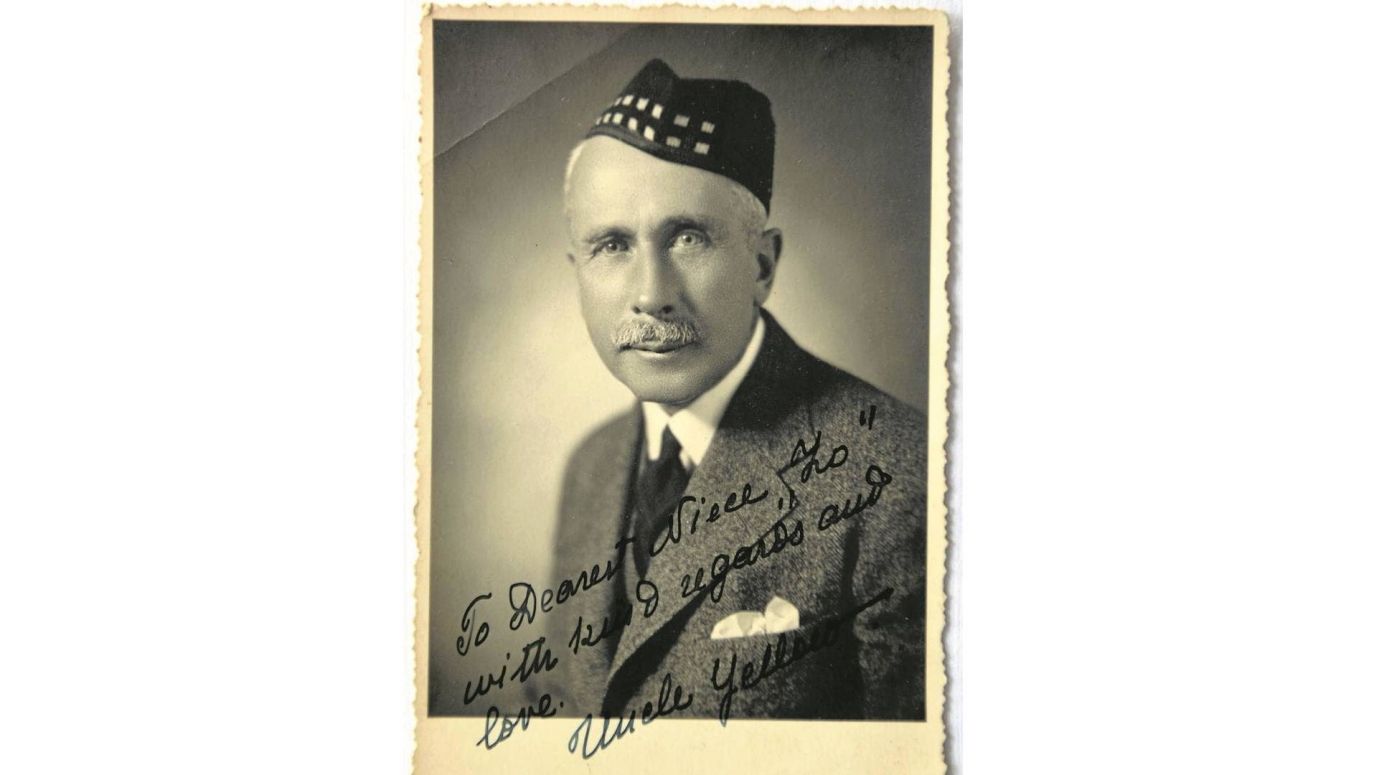

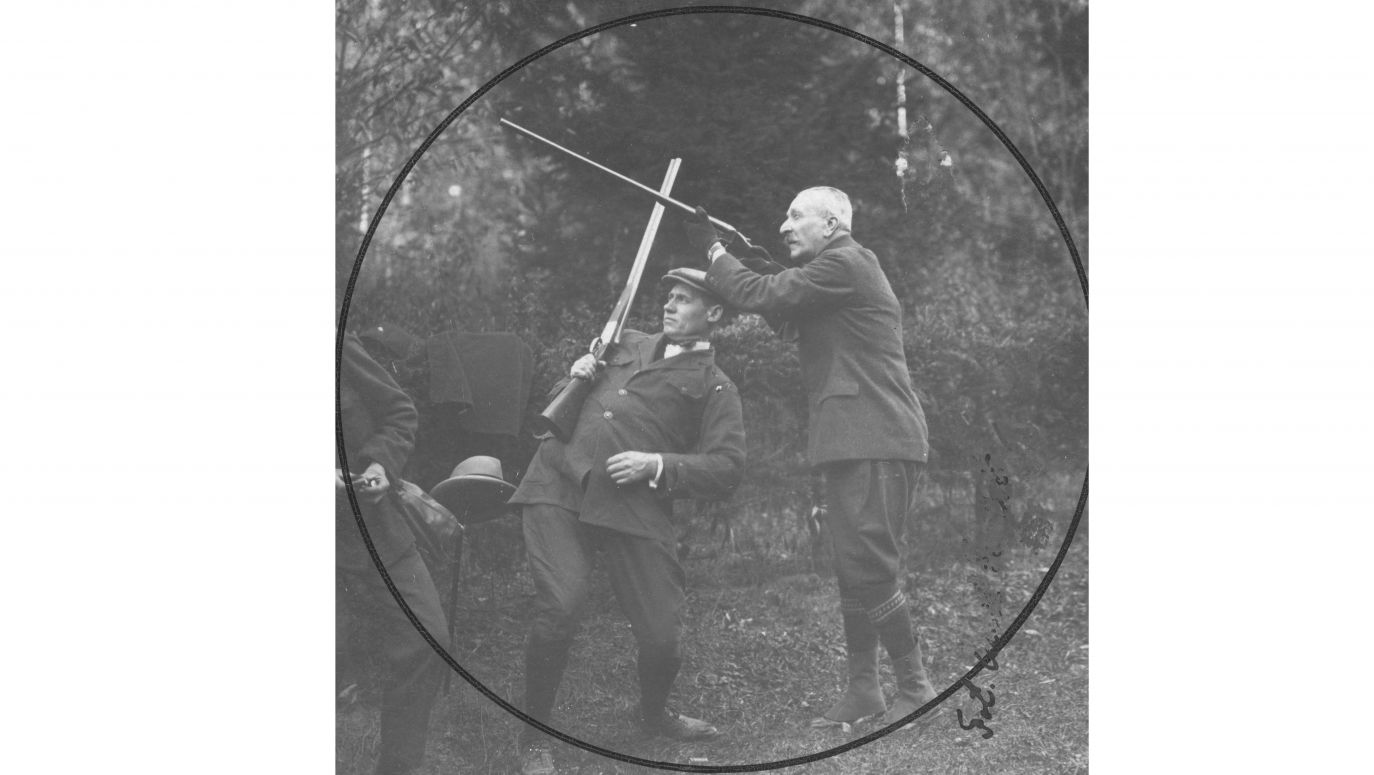

Mieczysław Jałowiecki, son of a great landowner from Lithuania, was at the same time, a few years before WWI, a young agricultural attaché at the Russian embassy in Berlin, shortly after his studies and doctorate. As a representative of the embassy, he was invited one evening by the commander of one of the Imperial Guards regiments to a formal reception. Among the officers dressed in gala uniforms, there was only one civilian, count Ledebur from the Austrian Embassy. Jałowiecki recalls:

“The commander of the regiment, with exquisite courtesy, introduced us one by one to the officer corps. A young officer was assigned to each of us as a cicerone. The choice was right, because I found myself under the care of a young lieutenant von Kempis, who turned out to be a Catholic and a landowner from the vicinity of Bonn. We sat down at the table in the large dark oak dining room. (…) At the end of the banquet the commander got up, followed by all of us. – To the health of the Emperor! – he cried out, raising his cup.

Holding the glasses at chest height, we drank the health of Kaiser Wilhelm. After three exclamations “hoch!” the German anthem sounded.

Then a toast was raised in honor of the Russian emperor. The commander and officers turned their faces and glasses towards me as a member of the Russian diplomatic corps. This was followed by a toast to the Austro-Hungarian Emperor. This time Mr. Ledebur was the subject of ovations.

The Austrian anthem

Gott erhalte, Gott beschutze unsern guten Kaiser Franz... ended the official part of the dinner.

Imagine, however, my amazement when the commander of the regiment rose from his seat and, with a glass in his hand, called on the orchestra. A cheerful melody

Poland has not yet perished rang out…

– Ihres spezial! cried the commander, raising his glass and looking at me.

– Hoch, hoch – the officers answered in chorus...” (Mieczysław Jałowiecki, “On the verge of the Empire”, Warsaw 2003).

The author of the memoirs points out that he became friends with lieutenant von Kempis and that he appreciated the officers of the Empress Augusta Regiment, representatives of the sphere where true values are valued, not only symbolic ones. Poland hadn’t been on the map for over a hundred years. No one in Europe had yet dreamed of a reborn Polish Commonwealth.

Manor replaced by an inn

Today, there is no such “institution” as the pre-war landed gentry, whose authority – recognized by the villagers – could effectively moderate the situation and prevent social plagues in the countryside. Because it was able to notice the problems of its inhabitants in time in a broader, nationwide context and react appropriately without delay.

The symbol of legitimate authority is never soulless domination, it is service. The mission of the gentry families in the Republic of Poland was to restore the existence of the state, and then to strengthen and defend our state, as well as to create and defend culture, the spiritual tissue of social life that unites Poles into one living organism. Landowning families were a model of life and a point of reference also in the matter of caring for the land entrusted to them by the Maker.

After years of devastation of the land by the state user who was never able to be an owner, it is clear how much our country misses landowners. The art of cultivating the land has often been turned into looting its resources, and its cultural landscape has also been destroyed. In the People’s Republic of Poland, the manor was replaced by an inn.

– Ewa Polak-Pałkiewicz

– Translated by Dominik Szczęsny-Kostanecki

TVP WEEKLY. Editorial team and jornalists

Quotes from: Mieczysław Jałowiecki, “Requiem dla ziemiaństwa [Requiem for the Landowners], Warsaw, 2002, “Na skraju imperium” [On the verge of the Empire], Warsaw 2007, “Wolne miasto” [The Free City], Warsaw 2009

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Communist propaganda was hostile towards Polish gentry, their culture and the attitude they represented. For the communists, the landowner was enemy number one because he personified respect for private property, patriotism and faith. And also respect for the priesthood, education, higher culture of behavior, social refinement. A way of being as far away from the nouveau riche culture as possible. Finally – the attitude towards Poland and the local community, which is best described by the word “civic”.

Communist propaganda was hostile towards Polish gentry, their culture and the attitude they represented. For the communists, the landowner was enemy number one because he personified respect for private property, patriotism and faith. And also respect for the priesthood, education, higher culture of behavior, social refinement. A way of being as far away from the nouveau riche culture as possible. Finally – the attitude towards Poland and the local community, which is best described by the word “civic”.