"Homo sovieticus" resides in liberals raised in communist Poland

02.11.2022

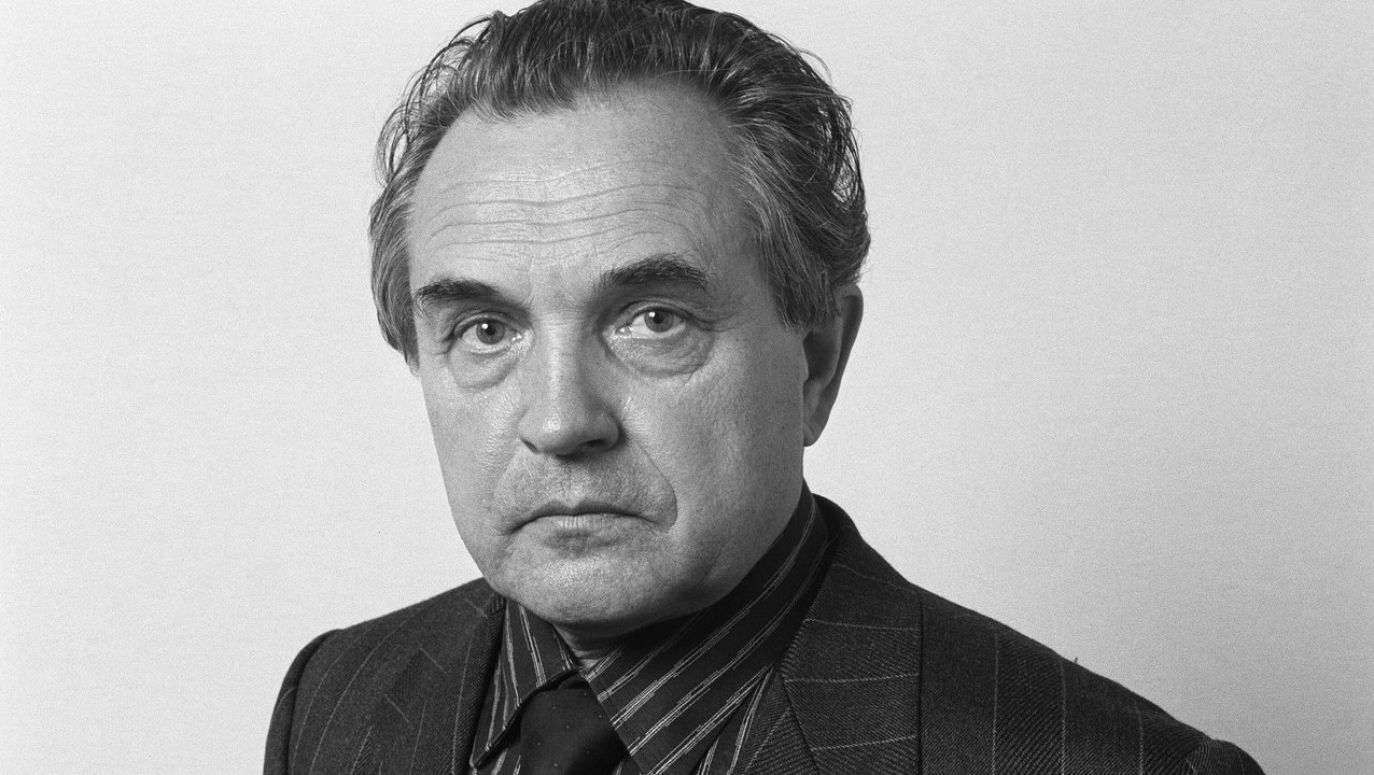

Alexander Zinoviev (1922 - 2006) believed that 'homo sovieticus' was a conjuncturalist adapting to all circumstances. And that it is a phenomenon that occurs in different political systems and in different countries. Therefore, it is worth considering whether it is not also present in Poland at the moment. But the term "homoso" needs to be properly defined.

In the 1970s, the writer began to cultivate a literary genre that has become his trademark. It was the sociological novel. The plot, which sometimes consisted of anecdotal situations, provided Zinoviev with a backdrop for reflecting on political and social phenomena.

He became famous with 'The Yawning Heights'. It was published in Switzerland in 1976. Two years later, also in this country, 'The Radical Future' was published. In this work, the then general secretary of the CPSU, Leonid Brezhnev, himself received a blow. Zinoviev's anti-Soviet pronouncements in his work earned him the disapproval of Soviet dignitaries. The result was severe. In 1978, the thinker and his family were expelled from the USSR. He lived in Munich until 1999.

However, it should be noted that the hostility that Zinoviev had towards the Soviet system was complex and not obvious. The writer sarcastically portrayed the society of the Land of the Soviets. Only that he was targeting not the state leadership, but the demoralised masses who, he believed, organised the Soviet order (including the repressive apparatus), so there was no reason to feel sorry for them.

In Zinoviev's novels, Soviet society is made up of numerous collectives, both smaller and larger. And these are structured into hierarchies within which it is possible to climb upwards, displaying the most despicable human qualities.

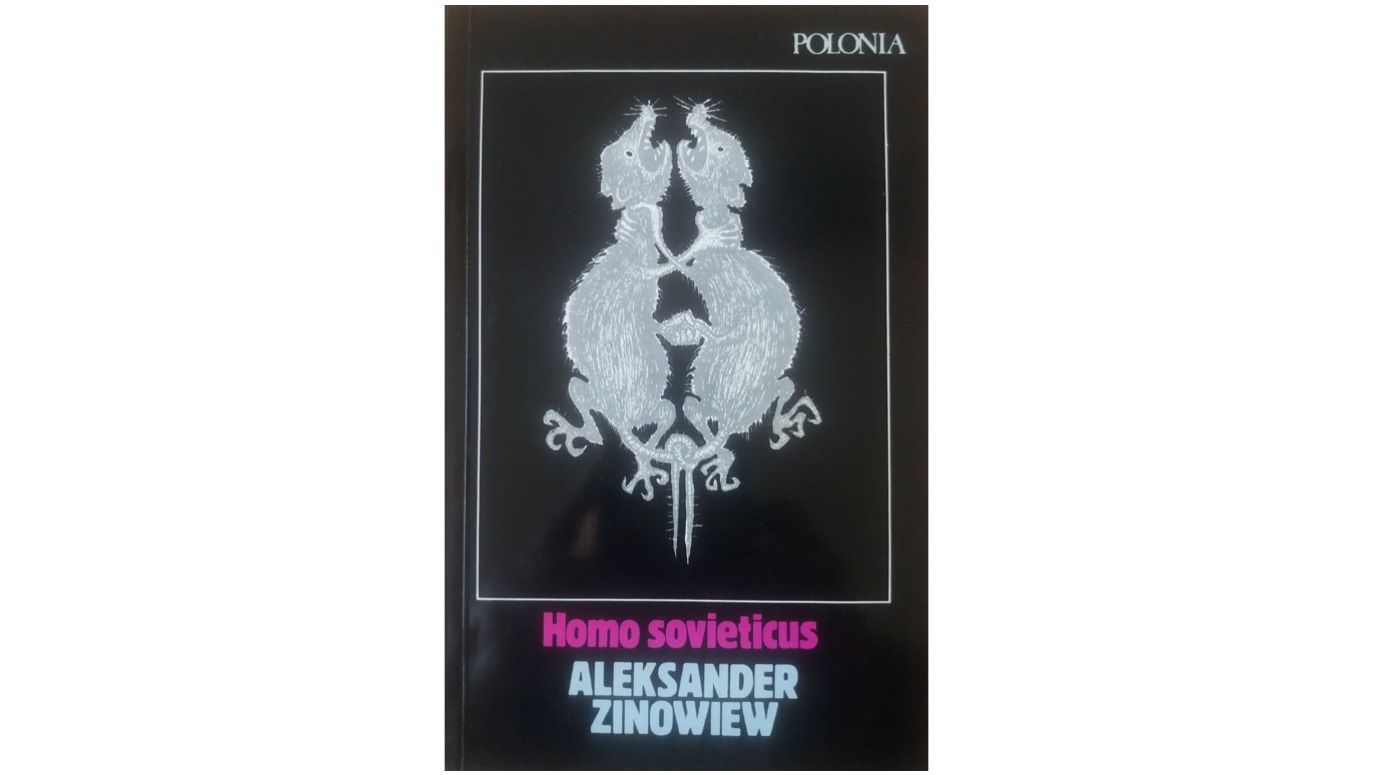

Zinoviev's novel 'Homo sovieticus' was published in 1982. It is a satire on émigré milieus - circles of people who, having come from the USSR to the West, retained such habits as conformism. But it is significant that the author by no means treats them with a sense of superiority. He also derisively refers to the eponymous type of man (abbreviated as 'homosos') as himself.

Stalin - a powerful leader, Gorbachev - a lousy bureaucrat

Zinoviev became known to a wide television audience in the West on 9 March 1990. It was then that he appeared in the famous cyclical programme 'Apostrophes', broadcast on France 2 channel, hosted by the well-known French literary critic and journalist Bernard Pivot. Zinoviev clashed in a duel with Boris Yeltsin. At the time, the latter was the leader of the reformist wing of the CPSU, in intra-party opposition to General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, whom he accused of having changed nothing substantial by the perestroika he initiated.

Meanwhile, Zinoviev attacked them both. When there was talk in the studio about the implementation of freedom of speech in the USSR, he mocked this and pointed out that his books were still not being printed in the Soviet Union.

What will the right-wing governments in Italy and Sweden bring to Europe?

see more

However, what may have been shocking to French viewers was something else. When asked how he reacted to the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953, Zinoviev replied that he had suffered a mental breakdown and even contemplated suicide. The writer explained that he had lost the meaning of life at that time. He argued that one can only fight with living people, and that since the enemy is dead, it is no longer possible to confront him.

At the same time, however, he praised Stalin as a powerful leader at the head of a state with which the world reckoned, and in which many people managed to achieve social advancement (Zinoviev, who came from a peasant family, from a Russian 'glubinka', was also among this group). Although, at the same time, he acknowledged that these 'achievements' came at a brutally high price. In doing so, he contrasted Stalin with Gorbachev, whom he in turn saw as a lousy bureaucrat.

And this was precisely how Zinoviev justified his negative assessment of the clearing of Stalinism carried out in the USSR during perestroika. In the discussion, the thinker took the position of a perpetual oppositionist, fighting only those politicians who are currently relevant. That is why, he claimed, over the course of his life he successively confronted Stalin, Nikita Khrushchev, Brezhnev and finally it was time for Gorbachev.

One of the main bones of contention dividing Zinoviev and Yeltsin, however, was their attitude to liberal democracy. It turned out that - unlike the future Russian president - the writer contested the setting of this political model as a benchmark for Soviet politicians. Zinoviev, in fact, came to the conclusion that the main danger for his compatriots was the disintegration of the Soviet state. He therefore opted - contrary to the expectations of the Western political elite - to strengthen, rather than weaken, power in the USSR.

The rule of global finance and the problem with China

Perestroika, in Zinoviev's eyes, had disastrous effects (which is why he called it 'catastroika'). I remember my interview with him, which I conducted in early 2006 for 'Europa' magazine. It was a few months before the thinker's death. At the time, he expressed his conviction that after the collapse of the USSR, Russia was becoming a colony of the Western powers. Not even so much Western countries, but - in his opinion - the global financiers ruling them, described as a 'super-society'. At the same time, he pointed out that Europe, too, by giving way to the US in many matters, was under threat. He predicted that with globalisation, the "post-democratic era" was fast approaching.

According to Zinoviev, the function of the 'super-society' can be compared to that of the Communist Party in the Soviet system. Theoretically, power in the USSR belonged to the Supreme Council, but practically the state was ruled by the CPSU. And in the same way, the mechanisms of globalisation are leading to the fact that, while all the states of the world - including the USA - formally remain more or less sovereign, they are in fact increasingly subordinated to the 'supersociety'.

As for Zinoviev's prognosis, in 2002, in an interview with him on the Russian television channel NTW by Alexander Gordon, the thinker declared that the main challenge to the West in the first half of the 21st century would prove to be the People's Republic of China. And let us recall that the public attention of the Western countries at the time was captured by America's confrontation with the jihadists. After the 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, fears that the world might be set on fire were aroused by al-Qaeda and the Taliban, not by China. From today's perspective, it can be said that the writer was not wrong.

In 1999, Zinoviev returned to his homeland. This was a demonstrative parting with the West. At the time, the thinker was opposed to the intervention of Nato troops in Yugoslavia to end the Kosovo conflict.

Thus, Zinoviev was given the image of an ally of the communists and the entire spectrum of nationalists, i.e. those political forces in Russia that prey on nostalgia for the USSR. I also raised this issue with the writer. He himself denied that he stands on any side of the barricades. He emphasised that he does not identify with any political camp and follows an individual, independent path.

And it is worth noting that he did not get on well with other Soviet dissidents during his exile either. Alexander Solzhenitsyn, for example, could be mentioned here. Zinoviev told me that his novel 'The Gulag Archipelago' was a "falsification of history". He insisted that Solzhenitsyn was exposing the repressive nature of the Soviet state, while overlooking, for example, the fact that the USSR had managed to educate many millions of people. At the same time, the thinker insisted that he was not an apologist for Stalinism.

What would he say now?

Zinoviev died in 2006, so he witnessed the first six years of Putin's presidency. And tellingly, he regarded this politician - like Yeltsin - as a servant of the West. The imperial turn that Putin performed were, for Zinoviev, meaningless appearances.

What is intriguing, then, is how the writer would currently respond to Kremlin policy. His widow, Olga Zinovyeva, who is regarded as the guardian of his intellectual legacy, makes statements which suggest that she supports Great Russia revanchism, including Moscow's invasion of Ukraine. By contrast, the affirmation of the power of the Soviet state during Stalin's dictatorship and the anti-Western content of the thinker's books and journalism can certainly appeal to Putin and others in the Kremlin establishment. Hence, this year's state jubilee celebrations in Russia should come as no surprise.

However, the appropriation of Aleksandr Zinoviev's oeuvre by the Russian political elite means choosing only what suits them for propaganda reasons from his work. Meanwhile, this writer loved to provoke. His work is characterised above all by contrariness.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

In Russia, the anniversary has been given state status. The celebrations of the centenary of Zinoviev's birth continue throughout this year. And his words were quoted by Vladimir Putin at a meeting of the Valdai Club last week. Why, then, does this thinker enjoy in Russia today the recognition of its dictator himself?

In Russia, the anniversary has been given state status. The celebrations of the centenary of Zinoviev's birth continue throughout this year. And his words were quoted by Vladimir Putin at a meeting of the Valdai Club last week. Why, then, does this thinker enjoy in Russia today the recognition of its dictator himself?