Jehovah’s Witnesses believe that the “scarlet-colored beast” is the United Nations, each subsequent attempt to microchip people is perceived by many as giving the Mark of the Beast and interpreting subsequent wars in the Middle East as fulfillment of particular turns in the struggle of the kings of Medo-Persia is the specialty of televangelist visionaries in the United States. But this curiosity has always been there – and the “decoding” of individual phrases was sometimes perceived as a sign of all-knowing, indeed, even used as a temptation... Let us only recall the monologue of the evil spirit in Dziady [Forefathers’ Eve by Adam Mickiewicz], addressed to the praying priest Piotr, a mixture of both trivial and the gravest temptations: “Do you know what the whole city is saying about you?... Do you know what will happen with Poland in two hundred years?... Do you know why the prior is not so favorable to you?... And do you know in the Apocalypse what the beast means?” Never mind the priorities of the prior, but who (probably also Trzaskowski’s voters) would not want to know what will happen to Poland in two hundred years – and the latter?

Grodzisk Interpreters

Who has not asked this question, not only among intellectuals, but also from those of simple nature! “Sodomagomoria!” – the grandfather began his monologue in the film Konopielka. The unorthodox Kasprowicz and the very pious Karol Ludwik Koniński studied the Apocalypse. Stanisław Rembek, a writer, it would seem, far from all passion, even dry in the perception of reality, in his splendid Dziennik Okupacyjny [Journal of the Occupation], published these days by the State Publishing Institute (PIW), several times, between reports on transports pulling through Grodzisk, prices of coal and vodka drunk by oldish, local patriots (this vision of Poland, in suburban Warsaw, lurking, skeptical and agile, perfectly complements the picture of the German occupation) confides in the afternoons and evenings spent with one of his friends, to reading the Revelation of John, reading it into contemporary times. “We came to the conclusion that the Apocalypse should be read in a different way than is usually done,” notes the newly-minted revelator, with somewhat touching pride.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

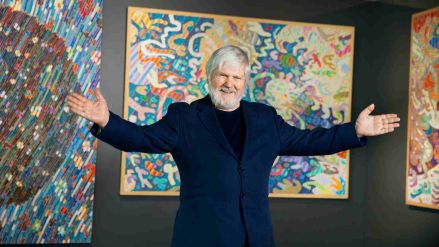

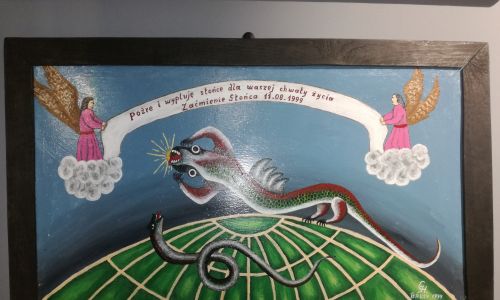

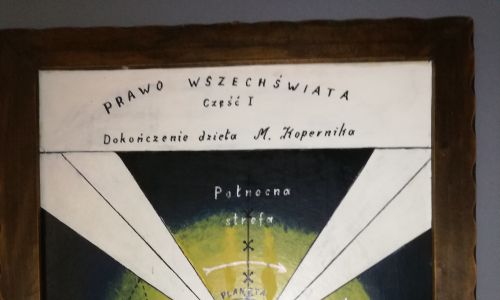

So he read the Apocalypse by Kasprowicz and Rembek, viewed it (or listened to it in church) from folk artists, who were almost as eager to carve a woman standing on the moon from linden wood, as a sorrowful Christ or a red-mouthed devil. But probably no one has mulled it over as deeply as Józef Chełmowski, a painter, sculptor, inventor and theosophist from the heart of the Kashubian region, from Brusy.

Born in 1934 in Brusy Jaglie, on the German side of the border that divides Pomerania (“I started my education in 1941 in Volksschüle in Brusy at the age of six” – he writes in the one-page “My creative biography”), and died in 2013, he lived his life – as happens with prophets and visionaries – in a completely common way, without academies and scholarships, spectacular passion and breakdowns, loud vernissages and scandals. The already quoted “biography”, a great testimony, even shows that his initial years flowed in accordance with the model curriculum vitae of a citizen of Communist Poland. “Then there was the Service to Poland [paramilitary, state youth organization] for six months in Silesia, where, for a high quota of 250%, I became a delegate to the first world Youth Rally in Warsaw. Before I was 18, I started physical work at the Polish State Railways [PKP] in Chojnice. After a few years, I went to basic service in the army, where I graduated from a non-commissioned officer school as a radio station commander. After leaving the army, I worked on a 12-acre farm and other state works”.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE