When Russia justifies its aggression on Ukraine in terms of the fight against “Nazism”, few in western countries take this assertion seriously. The murder and rape that Russian invaders undertake damage the image of the country that sent them there. But Russia hails itself as the inheritor of the Soviet Union or the conqueror of the Third Reich. But if the Kremlin aways reaches for the anti-Nazi rhetoric, it reflects its propaganda strength.

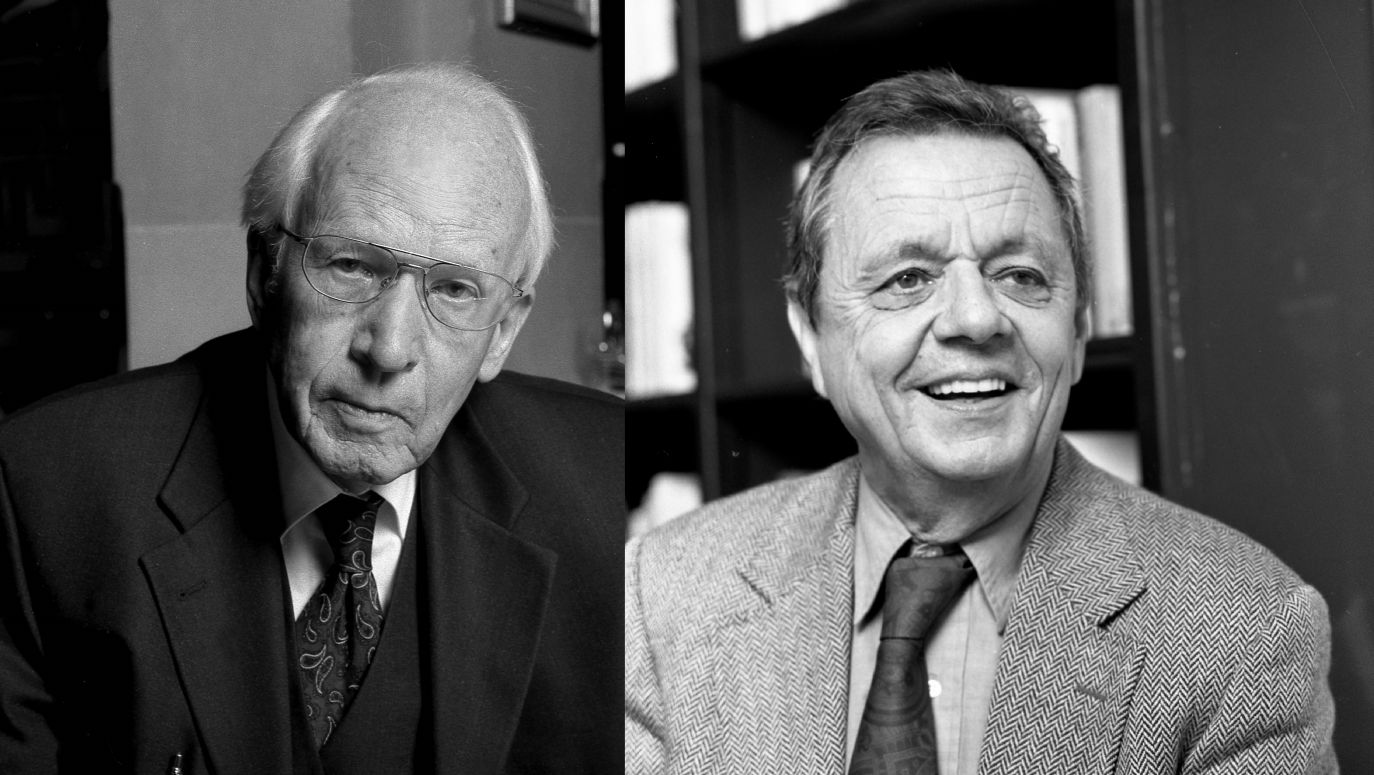

It is worthwhile reading the well-reviewed book “Fascism and Communism” (Translated as ‘A Close Enemy, Communism and Fascism in the 20th Century’) by François Furet and Ernst Nolte, recently translated into Polish by the Pilecki Institute in Warsaw. This is a collection of correspondence from 1996 and 1997 between Furet and Nolte, now both deceased. It is a discussion on the controversy surrounding totalitarianism

The starting point is the wide-ranging preface that Furet wrote in his book “The Passing of an Illusion” (which can be read in the above-mentioned “ A Close Enemy”) an essay on the idea of communism in the twentieth century. Ernst Nolte’s thesis developed in the 1960s and stunned Furet. It concerned the roots of German national socialism. In short, it could be argued that if it were not for Nazism there would have been no Soviet communism.

Nolte attempted to rationalise the motivations that directed the Nazis. According to him, Hitler’s project was a reaction to the threat from the Soviet Union and world communism. He maintains at the same time, that the mass extinction policy of the Third Reich against the Jews was modelled on earlier Bolshevik terror: the methods of the regime that the Nazis saw as enemies (hence the title of a close enemy referring to both totalitarianisms).

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Nolte touched on the taboo subject in the public debate of the West and that of West Germany in particular. He argued a blasphemous proximity between Nazism and Communism. In addition, he maintained that the Nazis as far as genocide went, imitated that of the Bolsheviks. He questioned the status of the Holocaust as an exceptional and specifically German crime. He was attacked by left-wing intellectuals in the German Federal Republic for this reason. It must be remembered that he gained much sympathy from German organisations of post-war expellees, a feeling that he reciprocated.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE