Who are Muscovites?

15.06.2022

Does a stage director truly believe that advocates of feminism, unrestricted abortion or LGBT people’s rights are tormented and persecuted just as were the Philomaths and Philarets in 1823, by tsarist officials. Does she believe in mass martyrdom of those environments, in a new Sibir?

At last I can! Warszawskie Spotkania Teatralne (Warsaw Theater Encounters) let me watch the celebrated spectacle “Dziady” (“Forefathers’ Eve”) of the Kraków Słowacki Theater.

Every time I “committed” any commentary referring to this event, I was momentarily admonished that I had no right since I didn’t watch. I would explain that I was not commenting on the entire Maja Kleczewska’s performance but on particular ideas. Which were thoroughly described and which the director herself made an object of journalistic debate, if I understand correctly – with everybody. I would also refer to the political emotions which were aroused over this performance. Now I am going to account what I’ve seen.

Allusions

But even watching is not everything. For the purpose of this adaption ten rows at the Dramatic Theatre’s main hall were removed, being replaced with a long slab – extended stage. Some sequences were played at the far end though I sat in the first row, I could hardly see anything – the opening scene of the rituals for instance.

To make things worse, seats were inserted on both sides of the stage, and in front of them viewers with tickets were seated on cushions - I must admit that the interest in the performance was enormous. Those sitting on the sides additionally limited the visibility of people like me. So I may have missed details that would require additional descriptions and comments. Please forgive me.

Some will say I'm nitpicking. But carelessness about the audience is also carelessness about the clarity of the message. It would be unfair to say that this does not happen elsewhere. In the "director's" theater it is the vision that counts more than the spectator.

Well, but with great effort I watched it. The performance began with a touching accent. A Ukrainian actress read “To our friends, the Muscovites”. This has probably been added recently – the premiere took place before the war with Ukraine. My perception was disturbed only by the intrusive question that haunted me: who will these "Muscovites" be in this performance? After all, it is a play about the artist's spiritual struggle, but also about a rebellion against the oppressors of Poland, against the tsarist, Russian despotism. And I've already heard that it is played as a story about something quite different.

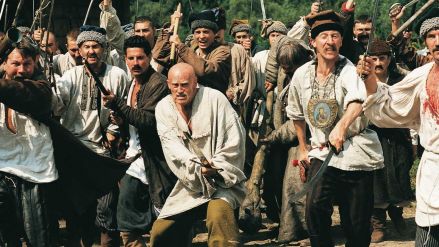

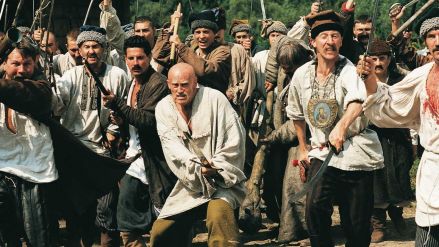

The scene of the rituals, I shall repeat, viewed with technical difficulties, immediately introduced us to the world of bizarre modernizing allusions. On the one hand, we have ghost visits played one after another. On the other hand, the crowd accompanying the Guślarz consists of a cross-section of contemporary Poland, as it is seen by the politicized Kleczewska.So there are football fans and nationalists, there are also gays and activists of women's protests.

At times they play scenes with ghosts, and at times they are preoccupied with the present. And this is about the fact that nationalists and football fans fuss and push the oppressed minorities. There is also a couple of Warsaw insurgents unexpectedly cast as children who need a grain of mustard seed for salvation, because “they knew no bitterness at all”.

It would seem that a couple of old people with a wartime past must have experienced a lot. But logic, rational interpretation, is the last thing we should be looking for here. I mean, there are meanings, but they flow alongside the text, like a stream of consciousness, without any particular concern for coherence and consistency.

Memes

Kleczewska has to shout her own. And this does not always happen ... What's the harm? “Who cares?” – as a certain American producer said when it was pointed out to him that the script of a historical film was loosely related to history.

As someone instructed me after the performance, the vision has its own rights. I will answer with a question: can it be gibberish then? Full of his own idiosyncrasies and obsessions?

Wasn’t Mickiewicz obsessive too, at times? These are, however, completely different obsessions. Kleczewska, wanting to shout her own words, could simply write her own text, even using motifs from literature, perhaps also from “Dziady”, but still separate. This is what - it must be admitted - Monika Strzępka for insatnce does or at least what she did in cooperation with Paweł Demirski.

But this director can’t make it. She fills words, sentences, dialogues and monologues about something else with intrusive symbols, one might even say memes. But memes do not morph even into decent journalism. What to talk about art. I know the view that each generation should subject the classics to reinterpretations, i.e. updates. But does this mean turning old texts into a sack of memes, for the purpose of your own prejudices and opinions?

The rituals scene ends with the appearance of Konrad transformed into the Phantom. This is accompanied by a very abridged text. After all, Konrad became a ghost out of love for a woman. Here Konrad is a woman – played by Dominika Bednarczyk. She is a woman walking on crutches. We know neither the cause of the handicap nor the reasons for the unhappiness. All the more so she won’t fit the fourth part, largely devoted to love torments of the romantic hero.

The same character ends up in a cell at a Vilnius convent turned into prison. The tsarist prison, it is so called here, although only women are incarcerated. Posed as activists of the recent Women's Strike, which the director emphasized. At the same time, Kleczewska is not able to completely change the text. One of the prisoners is still Felix. The main character is addressed “Konrad”. Is it a nod to a world where gender is a matter of a variable contract? Probably the result of overstuffing the drama. Well, it's a vision again! The director, or rather director and playwright (Łukasz Chotkowski), are said to have the right to do so.

So they are exercising this right. I must sincerely confess that due to the constant dissonance between what we see and what we hear, I was not able to experience a single piece of the scene in the cell as something dramatic. We watch rebellious women, but we listen to Sobolewski's stories (here an old lady in the type of a KOD [Komitet Obrony Demokracji – Committee for the Defence of Democracy] activist) about boys, students from Samogitia, transported to Sibir in kibitkas. By the way, the slicing of this text expresses an ideological tendency. We have a rebellious song: “Vengeance to the Enemy. With God, and even despite God”. We do not have a moment when Konrad defends the name of the Mother of God (although it is the Angel who later talks about it).

Metaphors

Two fundamental questions come to my mind. First: I saw many young people in the audience. Will they understand at all what it is about? What will their parents say to them when they ask about it. I pose such questions during each performance, when the processing of the so-called classics takes place. A reminder that “Dziady” is discussed at school as reading is a weak argument for me.

Second question: what is Kleczewska really trying to tell us? Does she truly believe that advocates of feminism, unrestricted abortion or LGBT people’s rights are tormented and persecuted just as were the Philomaths and Philarets in 1823, by tsarist officials? At the end of the scene we see an attack of collective hysteria of these women. Really, was it so at that time and is it the same now? Do you sincerely beleiebe in mass martyrdom of those environments, in a new Sibir?

Someone will say again that this is a metaphor. But after all, a metaphor must respect proportions, an elementary relationship with reality if it is not to turn into self-parody, into caricature.

Even the people of the Polish anti-communist opposition were accused of self-stretching out on a plush cross. But there were times when there were real risks involved in participating in it. You could be killed in Stalinist times. During martial law you could go to jail for several years. Today's scuffles with the police, sometimes also insulting or pulling the policemen, with eager consent of the courts, are to be martyrdom? In addition – national martyrdom, because Kleczewska did not manage to completely cut out the references to the endangered Polishness, which sounded strange on this occasion.

Adaptation of school readings in a computer RPG game? Polish teachers grasp at anything to encourage young people to read.

see more

In addition, the struggle to transform the society, to amend legislation or the social system suddenly becomes an apocalyptic clash between good and evil. One may wonder if Mickiewicz didn’t demonize the tsarist and heroize his colleagues beyond measure. But he was undoubtedly talking about struggle against tyranny. Today's ideological dispute is a classic clash of different values, in which it is very possible that feminists or minority advocates will achieve victory in a moment. In which dispute they are being supported by influential mainstream circles in the West. And yet they want romantic melorecitation to elevate themselves. I admit honestly that it makes me feel embarrassed.

Konrad the woman is left alone in the cell and begins the Great Improvisation. Even some spectators of those less delighted with this staging found it beautifully made. Indeed, the actress speaks well in verse, although I found some passages too hysterical. But while listening to this over half-hour long monologue, I was continuously haunted by the question what it was about.

The Great Improvisation tells the story of the creator's responsibility and his dreams to rule over his own nation. Eimontas Nekrošius, in his version presented at t National Theater (2016), suggested that this desire to create the world with words is somewhat mythological. Nevertheless, with him it was also about the artist. Here, the female Konrad in a cell is described as a poet. But he (herself) mentions a matter. About which one ? In this respect, there seems to be a lack of information here. What is this Conrad’s power over the nation for? For reforming it in the spirit of the European Parliament’ latest resolutions?

At the same time, this monologue in Mickiewicz's work is a rebellion against God. Although here, on the stage, behind of Konrad both Angel and Devils appear, the following scenes will show that the problem of God's presence doesn’t play a major role. But I am not nitpicking excessively. This is just a piece of pretty poetry, all contexts are ignored.

Pedophile Bishop

I do not know what Kleczewska thinks about the Divine presence in her version. It is possible that she believes in reconciling the reasons of religion with the emotions of progressive women. Exactly along the same lines, the director Adam Nalepa presented Antigone as an advocate of the pro-abortion rebellion in the Theater Academy's performance and at the same time ordered her to speak out about the superiority of divine law over the statutory human one. On the other hand, removing Konrad’s defense of the Virgin Mary from the scene in the prison cell would indicate that she is interested, quite mechanically, in the rebellion itself.

But in the drama we refer to the divine presence mainly via Father Peter. Meanwhile, in Kleczewska's work there is now a series of images that can hardly be considered coherent, meaningful and even consistent with the author's intentions. For me, it is quite disgusting to level contemporary ideological or political scores.

We are in front of The Altarpiece by Veit Stoss in Cracow. It is true that we have just heard that this is happening in Vilnius, but what does it matter? We meet Father Peter who is… a bishop. Why in Cracow? Everybody explains it by Kleczewska’s hatred for the archbishop Jędraszewski.

Father Peter was sometimes a young clergyman in Forefathers' Eve (Józef Duriasz in Dejmek’s adaptation, Mateusz Rusin in Nekrošius’ version) and sometimes an older man (Wiesław Komasa in the recent staging by Janusz Wiśniewski atpurpurat Teatr Polski). But always, and according to the text, he was a humble monk. Here, he is not only a hierarch, but also a pedophile, or at least an enthusiast of very young girls. Kleczewska introduces the usually overlooked Ewa's Vision, a rather naïve religious vision of – as a matter of fact – a child, only to end up making this child the victim of a haughty hierarchy (which is naturally absent from the text).

At the same time, this very Father Piotr in the episcopal robe is taking the exorcism of Konrad controlled by the Devils. But who's really bad and who's good? Lack of clarity. The evil spirits are initially separate characters. But then they speak with the mouth and voice of the unconscious Konrad himself. This is what possession is like. But, considering what Bishop Peter has just been working on, is it really possession, or is it a struggle of healthy freethinking against the backward clergy? I have no idea if the playwright and the director asked themselves this question at all. You know: the right to unfettered vision! Should they use Mickiewicz to fight against contemporary pathologies in the Catholic Church? Who cares?

In this situation the Vision of Father Peter acquires an exceptionally ambiguous character. Let me remind you that the clergyman sees Poland tormented by the tsar with the consent of other nations – she becomes a Christ of nations according to messianic concepts. One can discuss the archaism or exaggeration of this vision. br>

In this version, however, the actor who plays the priest (Bishop) Piotr, Marcin Kalisz, says it all in the tone of an uninspired buffoon. Does this mean that Kleczewska is trying to change the message, which Mickiewicz probably wanted to carry across? Or maybe if in this staging there are so many crude references to the present day, this is a mockery of the contemporary political messianism of the Polish right? After all, Father Piotr seems to be the embodiment of its flaws.

On the other hand, if the torment of Poland at the hands of the Tsar is something grotesque, rhetorical and exaggerated, the question returns: who are the Muscovites in this staging? It is possible that I overestimate the precision of the thoughts of the authors of this staging. But is it wrong to expect it?

Muscovites and nationalists

We won’t see the Warsaw Salon at all. And it could not be otherwise. In this scene, Mickiewicz portrayed a cosmopolitan, aristocratic and intellectual elite. It was her cosmopolitanism that, in the poet's view, was a paradoxical ally of the great Russian power. This is not a pronunciation that a progressive artist would care about.

On the other hand, when we move to the Senator's Ball (his Dream is in between), Father Piotr, played by the same Marcin Kalisz, is someone else. He becomes a monk, a brother in an ordinary cassock, interceding for Mrs. Rollison and slapped by a tsarist dignitary. Has he changed? After all, he dealt with Ewa with some embarrassment. But has he also changed his formal identity along the way? Only puzzles!

The scenes at the Senator’s are maintained in grotesque convention, which is in line with the general poetics of this fragment in the drama. Only that this exaggeration is too great – Mrs. Rollison, begging for her son's rescue, was brought here, performed by Agnieszka Przepiórska, to the screaming scarecrow. But Jan Peszek is a naturally skillful actor. Senator's Dream, a parody of the logic of self-possession with his servitude, is played with gusto.

After all, we will not get answers who the Muscovites are now, when we observe them in action. There are but hints. Kleczewska weaves Polish nationalists dancing among the courtiers into the scene of the Ball. In line with the hypothesis of an alliance between Putin's despotism and the autocratism of the Polish right. Is the hypothesis a true onne? This is not a hypothesis for me. It is polytgramota, pure propaganda, similar to presenting all opponents of the communist rule in the 1940s and 1950s as supporters of Nazism.

Of course, it can be continuously sheltered with platitudes about a legitimate artistic vision. I am more interested, once again, in the question of whether Kleczewska believes that in today's Polish state the mugger is whistling, the sarpath Botwinko is beating the brave progressive youth with a stick, and the kibbutzim are taking them to Siberia. Well, yes, the right to hyperbolize. You can set any nonsense to it.

The artist was too defiantly bourgeois to attract the attention of cultural decision-makers in Poland’s People's Republic.

see more

Anyway, answers to the interpretation may vary. Since the persecuted are female, the Senator's system might just be a bad male order. Worth breaking up in the name of feminism. But what does Father Piotr do in this breaking up? Has he converted to the faith of Maja Kleczewska?

Now it's time for the final. Guślarz discovers that one of the prisoners imprisoned in Siberia has escaped. I don't even want to bother myself asking about the meaning of this scene in this version.

Some of the defenders of this performance tell us not to ask about the meaning of individual pieces, but to surrender to the magic of the play in its entirety. The point is that the director herself encourages us to ask such questions by playing with allusions and memes. It is possible that she believes in the terror of the Law and Justice government equal to the tsarist one. And it is possible that it has more general intentions, such as replacing the old national drama with a new one, with the help, e.g. of a gender conflict.

In Jakub Skrzywanek's “Kordian” staged by the Polski Theater in Poznań in 2018, the allegedly raped artist ran around the stage with a microphone, convincing viewers that the former faults of tsarism and the fight for a free Poland are losing importance compared to contemporary atrocities.

It's just that Kleczewska's “Dziady” was staged just before the Russian-Ukrainian war, which suddenly made those 19th-century dramas and dilemmas relevany and vivid. And without a feminist context and moral. The director tries to connect one with the other, but she succeeds to a moderate extent and sometimes not at all.

It just so happens that this version of Dziady was staged at the Warsaw Theater Encounters shortly after the death of Ignacy Gogolewski and Jerzy Trela the same day. They both played Gustaw-Konrad: the first in 1955, the latter in 1973 (for many years, because Konrad Swinarski's Dziady at the Stary Theatre stage reached the martial law era). It’s a symbolic occasion to review past traditions. Someone may accuse me of starting with a description of Kleczewska's play, and not with squaring up to the question what the drama is about.

What was “Dziady” about?

Someone may also remind me of my inconsistency. More than once or twice, I accepted performances where something was added, where some modernizing meanings were added. Why did I like that and here I am complaining? Because at the end the question remains if it is allowed to use someone else's texts only for your own new story? And is it more interesting, wiser, more valuable than the original?

I could not see Aleksander Bardini's Dziady from 1955 at the Polish Theater in Warsaw. It was probably traditional, the very return to independence romanticism at the end of Stalinism was an important fact. Canonical were, as the preserved soundtrack and descriptions confirm, "Dziady" by Kazimierz Dejmek from 1967. The preservation of their religious significance was all the more paradoxical as Dejmek was neither a romanticist nor a man of faith. But such a reconstruction was considered to be a duty of a national theater. Produced on the stage of the National Theater in Warsaw.

The argument of many advocates of various deconstructions are Swinarski's Dziady from 1973 at the Stary Theater in Krakow. Some supporters of traditional theater did not accept it and I don’t necessarily mean conservatives from the right. Gustaw Holoubek, Gustaw-Konrad at Dejmek's, reportedly did not even enter the audience when he saw Cracow beggars in the lobbies gathered by the director.

Indeed, Mickiewicz did not write, for instance, a scene where, during the Great Improvisation, the peasants who had been present earlier during the rituals indifferently eat eggs. Swinarski added a number of new accents, sometimes he divided the contexts polemically towards the author. But it was still a great story about the artist's freedom, but also about the nation's pursuit of freedom. And of liberation from foreign despotism, and not from social rules. In this sense, he did not compromise on anything. And it was appreciated by Poles who over the years “made pilgrimages” from all over Poland to watch this spectacle. Searching, in the seemingly stabilized Polish People’s Republic, for dreams and longings – including the one to regain independence.

Later on, there were a few more adaptations, but also, especially after 1989, a slow parting from Polish Romanticism began to take place. Considered exaggerated, detached from contemporary realities, naive. In 2016, the Lithuanian Nekrošius staged this drama at the National Theater in Warsaw after a long break. He was mainly interested in the fate of the artist. National liberation threads much less. He put them in grotesque quotation marks. I did not agree with this approach. But I must admit one thing: this artist was not looking for an update by force. He did not fancy journalistic signals or allusions.

There were also attempts to give back to “Dziady” a more traditional meaning to mention a staging by Janusz Wiśniewski at the Polish Theater in Warsaw in 2019. The fate of this performance was influenced by a pandemic, but also by the belief that some scenes had failed and the whole thing turned out to be not entirely coherent. However, I think about him warmly, because you have to be brave to look for… Mickiewicz in Mickiewicz. Well, there it is.

The measure of some of the theater's people’s being blasé was, on the other hand, “Dziady” by Radosław Rychcik, staged in 2014 at the Nowy Theater in Poznań. The director decided that any content could be put into these words, in this case the topic of racism in the United States. In this sense, Kleczewska should be appreciated, because her version at least promises to talk about important Polish matters. The promise, however, is fulfilled inconsistently, with the old plot being stuffed into a form of contemporary journalism – intrusively, with hardly and care for logic.

It is said that the decision that one is allowed do to so was made a long time ago at a meeting of theater critics. At least - when I complained about Jan Klata's play "The Danton Case" – that was what I was told by a reviewer of Gazeta Wyborcza who is now inactive. Note well: from the perspective of what Kleczewska did with “Dziady”, Klata being much less radical in correcting, deconstructing, cutting and re-stitching. I shall preserve my opinion: such experiments should have their limits.

Behind Mickiewicz? Against Law and Justice?

Of course, it is difficult to agree to an arbitrary demarcation of such border. In this sense, both the Małopolska curator, Barbara Nowak, who tried to discourage school trips from attending the performance, and the management of the Małopolska regional council, trying to recall the director of the Słowacki Theater, found themselves in a dead end. By helping Kleczewska to shield herself with politics. In this narrative it is her opponents who are to be her symbol, not her. That, by the way, it is free advertising of the project, goes without saying for me.

However, it is hard to avoid the impression that many of its defenders are driven solely by political motives. Just as Krystyna Janda, who expressed admiration for the play shortly after the premiere, without watching it either. Or Piotr Fronczewski wearing a t-shirt with the logo of the show. Just a few years ago, in his interview, the same actor approvingly quoted Erwin Axer saying that the director's task is to “read the author's thoughts intelligently”. Are we really dealing with something like this here?