Instead of mazurek cakes, butterscotch wafers. Easter eggs to eat and admire. Galician cuisine unites Ukrainians and Poles

13.04.2022

Today, when Poles ask me how to host Ukrainians so that they feel at home and, at the same time, get to know some Polish dishes, I say: żurek (sour rye soup) and pierogi ruskie (dumplings with cheese and potato stuffing). This will be a combination of typical Polish and Ukrainian flavours. However, cheese dumplings in Ukraine are usually served sweet, so in Poland they would be suitable for dessert. And sour soup in Lviv tastes completely different from that in Warsaw – says professor Ihor Lylo of the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, director of the Institute of Galician Cuisine.

TVP WEEKLY: Cuisine historically unites our nations, Poles and Ukrainians. Perhaps even more so than many other things.

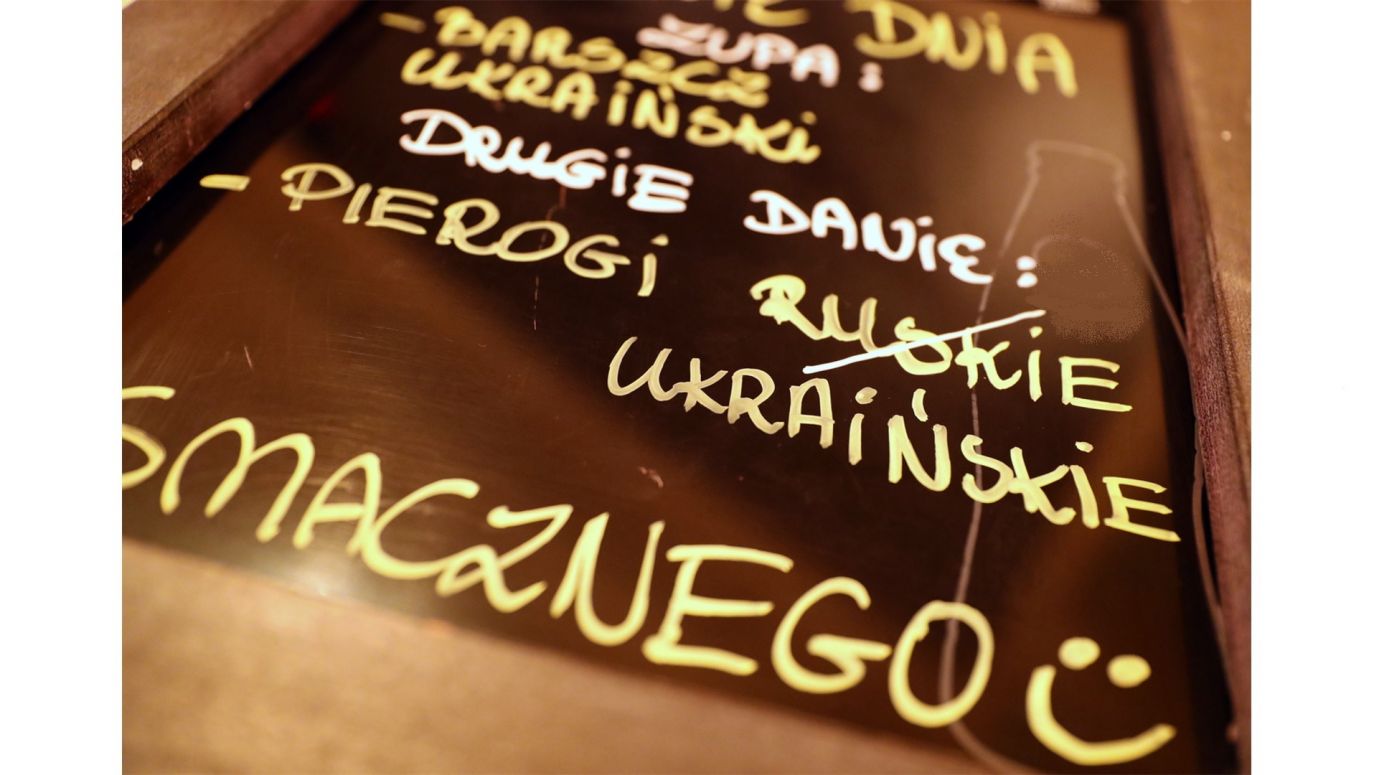

IHOR LYLO: Let me start by saying that Professor Jarosław Dumanowski from the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń and I are planning to write a serious article about Russian dumplings, in which we will argue a bit – which supposedly increases the appetite (laugh). To the world, these dumplings are a symbol of our two cuisines, Polish and Ukrainian. It is worth noting, however, that only today, with the ongoing Russian aggression in Ukraine, many Poles have realised that pierogi ruskie do not mean “Russian”. This is a very good thing, because they not divide, but unite us.

Why did you, a historian, take up the subject of cuisine? It’s a tasty subject, but unlike war, politics or even science, firstly it’s niche, and secondly the so-called sources are often hard to come by.

Cuisine is extremely important for a historian, even if he or she deals with politics or wars, because it is one of the essential elements of a nation’s identity. Ukraine is probably the only country in the world where, in order for people to go hungry or even die of hunger, it has to be planned and implemented as a political agenda. It must therefore be an artificial process, as, for example, the Holodomor was, because a natural famine on fertile Ukrainian black soil would never have occurred. And there were several of them: in 1932-1933 and 1946-1947. This was deliberately done by Russia, not only to humiliate the Ukrainians, but simply to break their sense of national identity.

Ukraine has always been the granary of Europe and now even of the world. I recently attended an important scholarly event online at New York University, where it was already being discussed with great concern what will happen in the world, and particularly in North Africa or the Middle East and many other places, if there is a shortage of Ukrainian grain this year. The current military action will mean that, as they say, “the bread will not be sown” and therefore, six months later, it will not be harvested in my country.

I am not surprised that before the current war, Russia conducted a huge campaign to promote Russianness, including Russian cuisine, by incorporating Russian dumplings and borscht. After all, they have their national dishes (e.g. coulibiac, shchi), but they have not used them, and they want to appear or dominate on the gastronomic map of Europe through Ukrainian and other cuisines. Therefore, a historian who deals with cuisine in our region, which was not known and appreciated abroad for a long time, has something to do. Although he may hear from his colleagues that there is no point in researching it if we know that “it is ours anyway”. However, the world today is founded on branding, so if you do not present your own cuisine accordingly, it will either be seized by such “difficult” neighbours, or it will be annihilated by the processes of globalisation. Then we will no longer know about those dishes that were so prized by our ancestors.

I wouldn’t worry about the “globalisation of pierogi” in the sense that they are unsuitable for chain restaurants or fast food, because to make them really tasty, you have to knead them by hand from paper-thin dough. However, I have read up on your academic path, and I understand that you specialise in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages in the area of Byzantine influence. So where does this “Galician cuisine” come from?

Indeed, I did my Habilitation thesis on the topic: “Greeks on the territory of the Ruthenian Voivodeship from the 15th to the 18th century”. The territory of this province included cities such as Lviv and Zamość. It was always a place where many cultures and tastes came together. The history of the Greeks in the Crimea or in Mariupol or Odessa had been worked out before, while the Ruthenian Voivodeship was a blank spot on the map. And there was a very interesting Greek and Armenian diaspora, for example in the Lviv area. The Armenians were mentioned and written about, but nothing about the Greeks, despite the fact that in Lviv there’s a Russian Orthodox church with a beautiful renaissance tower named after Konstanty Korniakt, and he was Greek by descent.

The Greeks living in this area in the 16th and 17th centuries came mainly from Crete. They were subjects of Venice and imported a, no trifling, 2 million litres of sweet Malvasia wine a year through the Lviv customs house. It was highly valued by both the nobility of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the rich bourgeoisie. It was also the Greeks, along with the Armenians, who brought to our land products so indispensable in the cuisine of the time, such as lemons or fragrant Mediterranean herbs, and finally olive oil, needed by wealthy people to keep numerous fasts. The rich had enough of it to use in their kitchen, the poor – not necessarily. But as I said, they did not starve either.

While researching this Greek topic, I asked the question: and who ate all this and how? What was the cuisine of the inhabitants of Lviv or Zamość like at that time? There was a need for reseach, not only academic but also popular science. And so my first articles on the cuisine of this region in the 16th and 17th centuries were written. I discovered that the readers found this subject very interesting. This pushed me to write books, and after writing “Lviv Cuisine” I met professor Dumanowski, with whom we have been cooperating so fruitfully for the last years.

So now we must jump from the Ruthenian province of the Polish Crown to post-partition Galicia. Not, of course, to the land of the Gauls on the Iberian Peninsula; our jump is more temporal than geographical.

Here it is necessary to talk about the Galician Cuisine Institute, an NGO that cooperates with academic circles, established in 2013. The name “Galicia” is somewhat conventional here, not popular everywhere in Poland, as it is associated with the partitions. In Ukraine, on the other hand, the name “Halyczyna” is perceived positively, because we hear in it a continuity even with the times of Ruś Halicka (Red Ruthenia). We chose this name because at the time when this part of the territory of Poland, Ukraine and even a piece of Slovakia was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, not only were the laws or communication systems in this area put in order, but people started to really think about local cuisine. The question: what do we eat and why?

This is a combined legacy of Polish-Ukrainian-Jewish-Armenian-Greek...

Austrian, Hungarian...

Sanctions will hit the young city hedonists or yuppies the hardest.

see more

Yes, and I could go on and on. From strudels to cheesecakes, and lots of other things in between (laugh). So this multinational cuisine was created in this area much earlier, but in Galicia at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries it underwent a significant reorganisation or even, one might say, self-creation. The name of the Institute is intended to reflect this, although today, after several years of research and the presentation and tasting (laugh) of our results, often in international circles, we see the name somewhat differently than at first.

It is, then, a fairly young cuisine for European standards. However, certain products and dishes or even customs may have a much earlier origin?

The cuisine is new, but based on old, often even medieval traditions. So when people ask me what they must try in Lviv, I say cheesecake, for example. It came to us from Vienna but was perfected in Lviv to such an extent that we consider it to be our own dessert.

I’m sure that the next time we visit Lviv, after the war and a fair peace treaty, God grant, we all try this cheesecake. So what is special about Galician cuisine compared to that of its neighbours? To trivialise the question: what do people eat near Lublin or Kyiv that they do not eat in Lviv, or vice versa?

Le’'s start with how Polish cuisine differs from Ukrainian. When Poles ask about it, they mean the cuisine of the former southern borderlands, let’s say up to Kamieniec Podolski. And Ukrainian cuisine as a whole has a lot of specific regional varieties: for example, Bessarabian cuisine with its centre in Odessa, Podolia cuisine which revolves around Vinnytsia and Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky, or fantastic Poltava cuisine, the symbol of which is the famous “halušky”. And of course Transcarpathia, where the Ukrainian, Hungarian, Slovak and Romanian influences resulted in a very interesting fusion of many flavours. Galician cuisine is only one of the Ukrainian regional cuisines. Poles are often not familiar with the cuisines of central or southern Ukraine. And the country is large and gastronomically diverse, just like Poland. Generally speaking, I’m more and more convinced that Poles prefer sour flavours in their cuisine, while Ukrainians prefer sweet ones.

This may be so, hence the cheese pancakes now made in our homes for breakfast by our guests from Ukraine.

That’s why today, when so many Ukrainians came to Poland because of that cruel war, and Poles ask me how to host them so that they feel at home and, at the same time, get to know some Polish dishes, I say: żurek (sour rye soup) and pierogi ruskie (dumplings with cheese and potato stuffing). This will be a combination of typical Polish and Ukrainian flavours. However, cheese dumplings in Ukraine are usually served sweet, so in Poland they would be suitable for dessert. And sour soup in Lviv tastes completely different from that in Warsaw: it seems greasier and they serve boiled potatoes with a spicy sauce as a starter.

And if we’re talking about special dishes from Lviv, we’re definitely talking about various breads that are made here, and Marian Hemar wrote a poem about one of them, “Kulikowski Bread”. It was named after a small town near Lviv, but was later made and sold in Lviv itself. Or a variety of blood sausage called “bulbianka”: maigre, because there’s no blood or animal fat in it, and it has a potato filling – a kind of potato pudding.

We have dishes of Jewish origin on Ukrainian or Polish Galician tables, which people no longer associate with being Jewish. We should certainly mention gefilte fisz or Jewish-style carp – an invention of Ashkenazi Jews, as well as hummus, which is very popular nowadays. In Lviv, the “Jerusalem” restaurant even makes a mix of five flavours. Beets with horseradish, so called ćwikła, are also of Jewish origin. Mikołaj Rey uses this name in his book “Żywot człowieka poczciwego” [The Life of a Good-Natured Man], but the dish is different there. Nowadays, ćwikła is served on a daily basis, and not only on festive occasions as it used to be in the past.

Another specialité de la maison is called pieróg biłgorajski in Poland, and Javorovski drumpling in Ukraine. It is served near the border, from both sides: Lubaczów–Jaworów [Ukr: Яворів - ed.], 60 km apart. A fantastic dish, underrated, healthy, cheap and interesting...

Is this a baked dumpling, made from yeast dough or shortcrust pastry?

Yes, and the main ingredients of the stuffing are buckwheat groats and potatoes. It can be pork crackling, it can be maigre, and the most important thing is that it is served with good quality cream. This is a dish from Roztocze which unites Ukraine and Poland. We can also mention Lemko white borscht, which people still remember and make.

You mentioned ćwikła, which is traditionally an Easter dish, because horseradish was used as a Paschal ‘bitter herb’ in the cuisine of Jews in Poland. As the granddaughter of a Galician housewife, I will also tell you about horseradish with eggs, a unique Easter masterpiece which is made in Poland only by people who come from a 100-150 km circle around Przemyśl. This is how it is done: the yolks have to be taken out of boiled eggs and mashed with broth and vinegar, hot, then the whites cut into shavings and horseradish – not grated, but skewered with a knife into long thin shavings, laboriously cut on Good Friday in the morning, with tears in my eyes. All this is kept in a jar in the fridge until Sunday morning. Then you add the blessed horseradish from the basket, and the rest of the root goes into the soup – pickled borscht or sour rye soup. Without horseradish and eggs there wouldn’t be Easter.

Yes, the horseradish in the Easter basket has various additional symbolic meanings for Ukrainians. They believe that this horseradish makes a person stronger, grounded in faith. Easter eggs, on the other hand, are of two types in Ukrainian culture. Firstly, Easter eggs are one of the great symbols of Ukraine, probably on a par with embroidered shirts. Ukrainian Easter eggs differ from Polish ones in their ornamentation, they have symbolic meaning and are not eaten. The second category of eggs are the ones we eat – so called kraszanki, dyed in onion skins in various shades of maroon.

For me, Galician Easter means a lot of food, it is more sumptuous than Christmas, because the fast preceding it is, I have the impression even today, stricter than in other regions of Poland. Maybe it is some kind of influence of the Orthodox Church. And there is not only more meat, but also cakes on Easter. So let us talk for a moment about the cheese paskha. Because I don’t think any mazurek or baba cakes are served in Galicia, but there are many sweets made of cheese.

Paskha (pronounced more like Pascha) is very important to me personally, even though my mother passed away two years ago. I remember well how, every year, she was terrified that the Passover would be as she had dreamed it would be. Because God forbid that the Passover should fail. That would be a very bad sign for the family. “Pascha serna” is one of the symbols of Easter in Galicia. However, there are many types of this dessert, such as the Roma (Gypsy) Paskha. I first came across it thanks to my colleague Marianna Dushar, who first researched the subject. It is a cake about 40 centimeters high! It is baked in a special way. This example, by the way, shows us another ethnic group which lived in this area and contributed their own to the common Galician melting pot – among other things, horseradish was a Romani speciality.

When we talk about Passover, it should be remembered that it was made in such large numbers that, several weeks after Christmas, when it had dried out, it was still eaten after being soaked in warm milk, thus producing a sweet quasi-milk soup.

In Poland, sweet Easter is associated with mazurek cakes, but my Galician grandmother didn’t even know what a cake was. For Easter, she used to make andruts layered with kajmak, i.e. wafers with a paste made from milk cooked for hours and caramelised thickly with sugar and butter. Now they sell kajmak in tins in shops (laugh).

Yes, such a multilayered, high andrut is first pressed down firmly to make it stick together well, and then cut. It’s terribly sweet, almost like nougat, traditionally it could have various flavours: rum, coffee, chocolate or raisin... Five years ago I recklessly agreed to be on the jury of an andrut competition in Lviv. More than 150 participants showed up and every andrut had to be tasted! Most of them were amateurs, not professionals, and yet it surpassed my wildest imagination as to how various pastes people can make andruts with. For example, with rosehip jam – a Galician speciality.

I make it myself – raw jam from the petals of a wild rose with intense pink flowers and golden eyes. You have to collect the petals after the dew, when there has been no rain for three days. You need to add as much sugar to the volume as the petals when you cut out the white, bitter petal tips and stuff the pink parts into a dish, e.g. a glass of petals and a glass of granulated sugar. Twist this mixture in the macerator with a wooden roll, then put it in a clean jar, seal it and keep it cool. It will never spoil. I add a bit of jam to doughnuts for Fat Thursday, because it smells and tastes wonderful. And you say you can spread it on andruts? It’s like making them out of gold.

This jam is still very widespread in Galicia. It is therefore not just for holidays, although it is indeed labour-intensive.

The period around Easter is associated with celebrations of all the once major Galician national and religious groups: the Catholic Poles, the Ruthenians of both Orthodox and Greek Catholic churches, and finally the Jews. Traditions related to fasting and eating began with Orthodox Seropust Sunday or Catholic Ash Wednesday (depending on how the calendars turned out), then came Jewish Purim – joyous and full of sweets – and so on until Pascha or Easter, which for different rites fell on different dates.

There were three calendars and the Jewish one was very important before the Second World War, but today those people are no longer there. Galicia came out of that war terribly mutilated. The situation in the east of Galicia, of which Lwów was the capital, was different from what it had been in Krakow and the surrounding area. Until 1939, Poles made up 50% of the population of Lviv, Jews 30-40%, Ukrainians 10-15%, but once you stepped outside the city gates, you found yourself in a rural, almost exclusively Ukrainian world. That’s why Easter in the city of Lviv and in the villages were very different holidays, although the Christian symbolism was common, only the “decorations” were different.

However, the pre-war Jewish world is no longer there, and the post-war Jewish world is made up of immigrants, who maintain almost no religious traditions, often coming from atheist or communist families. This leaves Catholic and Greek Catholic holidays and Polish-Ukrainian traditions as important, although Poles in Lviv today account for only around 10% of the city’s population. The tradition of the Julian calendar and the Ukrainian table therefore dominates. Little has remained from that pre-war world and I doubt that this will change. Furthermore, the current war has displaced people from the east to the west of the country – for how long is unknown – and this may affect tradition and cuisine and many other aspects of Galician life.

So let us try to experience Easter from the kitchen with our guests from Ukraine and let us surprise ourselves. Let’s imagine that somewhere around Lviv we sit down at an Easter table 100 years ago, today, and in half a century – is there anything that you think has lasted and will last?

There are two things. I have already mentioned Easter eggs, and the second thing that has amazed me even more in recent years is salt. It is carried in a Galician Easter basket to be consecrated. The very name ‘Galicia’, according to some linguists, comes from ‘gał’, meaning salt. It is found from Wieliczka to Drohobycz. It has its own characteristic taste, different from other salts, and adds that taste to dishes. We don’t think about it every day, but the subject of Carpathian rock salt is becoming culinarily and historically important. Let’s not forget that there has been an uninterrupted salt mine in Drohobych for 1000 years! Salt is not extracted there on an industrial scale, but it is extracted nonetheless.

The same goes for honey, an export product from this area for 1000 years. Right on the border, some very interesting experiments are taking place, involving the search for places where endemic flowering plants grow, which can be used by bees to produce honey unique in taste.

Before the beginning of the current war the Galician Cuisine Institute managed to bring back to Lviv an endemic plant called kleparov cherries. These plants are already planted in the botanical garden of Lviv. The first mention of them was found in documents from 1555, but this fruit tree disappeared between the 19th-20th century. It was found by us in Poland and reintroduced to Lviv, where it originally comes from. I hope that the trees will bear fruit in a few years and the taste of jam or other things will be unusual, because the tree bears a fruit intermediate between a sour cherry and a sweet cherry. We do not know the taste, because no one who dealt with it and is alive today.

There are more flavours of Galicia, which is why Marianna Dushar’s and my book “Lviv Cuisine” was written. It is likely to be published in Poland this year and I am convinced that it is not the cuisine of the past, but the cuisine of the future.

– Interviewed by Magdalena Kawalec-Segond

– Translated by Jan Ziętara

Prof. Ihor Lylo of Ivan Franko National University in Lviv, historian, specialist in the history of cuisine, visiting professor at the Jagiellonian University. He is a scholar of the Polish Academy of Sciences, was a Fulbright scholar (U.S.). Author and co-author of popular books, of which “Ukraine: food and history” was awarded by the prestigious Gourmand World Cookbook Awards in 2021 and has just been published in French.