War, wine, Nazis and the French. The unobvious heroism

08.03.2022

Wine was flowing freely. Incidentally, in France it was only in 1956 that children were forbidden to bring wine (though usually diluted with water) to school, because their grandmothers and grandfathers frowned on tap water.

In 2001, a famous and important book was published by an American journalistic couple living permanently in Normandy – Don and Petite Kladstrup – “Wine & War. The French, the Nazis, and the Battle for France’s Greatest Treasure”. It concerns wine and talks about how French winemakers resisted the fascist aggressors. And how they were robbed of their wine treasure. They cleverly hid the wine in various caches, by building extra walls in the cellars and shaking out the rugs over them to make them look genuine and old. But a winemaker, by nature, does not live off storing wine, but from selling it. It turns out that the occupiers paid very well for French wines and, what is more, traded them across the occupied Europe.

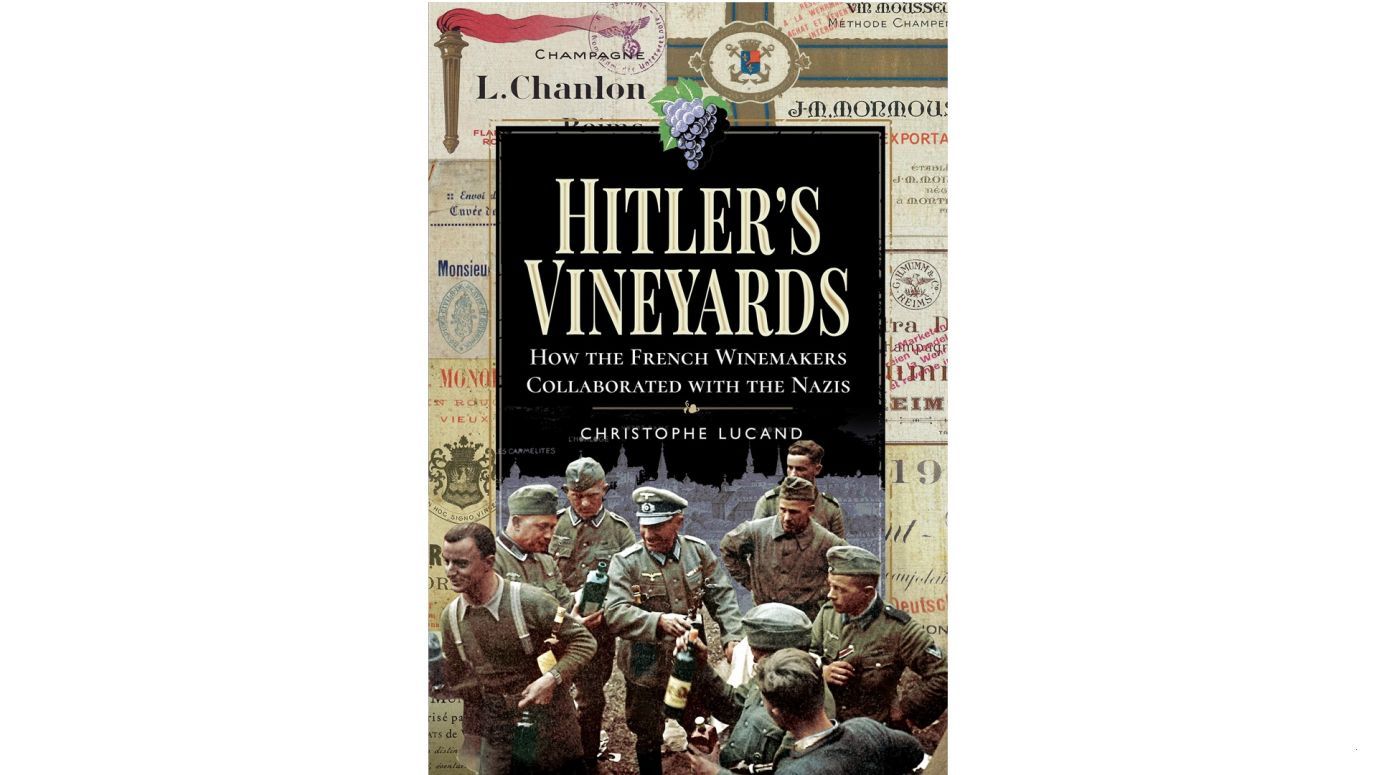

Christophe Lucand is a professor at the renowned Paris Institute of Political Studies (Sciences Po), a lecturer at L’IUVV (l'Institut Universitaire de la Vigne et du Vin “Jules Guyot”) in Dijon (Burgundy) and at several other research centres. In his recently published book “Hitler’s Vineyards” he offers a novel perspective of the issue: the Germans saved many failing wineries, many of which even made fortunes from the war – and the author provides many examples for that.

As a historian, he does not include interviews with often very famous wine families who had to flee from the aggressor to escape death because, for example, they had “bad” ancestry. Or they were tied in with the areas incorporated into the Third Reich, such as Alsace or Lorraine, and did not want to be conscripted into the Wehrmacht. As a professional historian, Lucand dug through tons of documents to investigate what the situation was really like.

French winemaking in the 1930s was in a deep economic crisis (just like the rest of the world), even though the general population consumed around 135 litres of wine a head. Other sources say as much as 180 litres, but the actual statistics are impossible to establish – some winemakers kept some wine for themselves and their families, other farmers had small backyard vineyards to also support their annual needs – this, however, is not included in the statistics. That said, bearing in mind the love of the French for various other liquors – be it pastis, apéritif, cider, digestif, cognac, armagnac, calvados, as well as whisky, it would be easy to conclude that the country was on the brink of an alcohol addiction (or perhaps this line had already been crossed?).

Wine was flowing freely. Incidentally, in France it was only in 1956 that children were forbidden to bring wine (though usually diluted with water) to school, because their grandmothers and grandfathers frowned on tap water. The American wine market, the largest in the world today, did not exist (as it was still recovering from the Prohibition), nobody even dreamed of the Far East, and in London wine was drunk only by the upper classes, which was not much.

The French authorities tried their best to curtail alcohol consumption. That, however, was difficult, because during WWI wine became part of French national culture, a symbol of patriotism. Many claimed – Marshal Philippe Pétain being one – that it directly contributed to victory by boosting the soldiers’ morale. He even wrote an introduction to the book “Mon Docteur, le Vin”. Besides, as many as seven million people worked directly or indirectly in the wine industry in France.

It is widely believed (and evidenced by almost all sources) that the mid-1930s introduction of the system of appellations, aimed to protect the name and area of origin for various wines, was intended to curb wine adulteration. This was probably the case, but by introducing appellations, on the other hand, the law gave winemakers the opportunity to use a famous wine-name and forced them to accept limits on production efficiency.

The Kremlin's economic pressure on the region's economies has a military effect. Washington sees this better than Berlin or Paris.

see more

Appellations were not very successful, since 30 per cent of French wine at the time came from Algeria, which was also French. This Muslim country was then the largest wine exporter in the world! Cheap wine was transported by tankers from Provence, Languedoc and Roussillon. Other attempts included: the introduction of “social rates” (fixed prices for wine), subsidies to lower production, or mass distillation. But the increase in production and the fall in wine prices could not be avoided.

A pact before the war

On the morning of 21 August 1939, the International Wine Congress opened with great pomp in Bad Kreuznach (Nahe region in Germany), located on the Berlin-Paris railway line. It was the first event of its kind in Germany and was attended by representatives from 24 countries, the highest representatives of the Third Reich, the NSDAP, the Wehrmacht and, of course, Hermann Reichsle himself, the representative of winemakers in the fascist government, and Edmond Diehl, the head of the event, who quoted Goethe in his opening speech. The congress was to last until 26 August and then turn into a meeting of German winemakers and continue until 30 August.

The programme was extensive: boat trips on the Rhine, visits to local castles and vineyards, philharmonic concerts, visits to Wiesbaden and Mainz, not counting gourmet meals. There were even wax figures of grape pickers set up in one of the vineyards. It was beautiful, sunny and warm. The Germans decided to use the event for propaganda. A message arrived with greetings from Hitler, Herman Göring (offstage, a lover of French wines) and Joachim von Ribbentrop (formerly a wine merchant who imported German wines to Canada, but was better off in his marriage to Miss Anneliese, or rather Anna Elisabeth Henkell, daughter of Otto, a wealthy wine producer from Wiesbaden – Henkell is to this day one of the biggest giants on the world wine market).

Because of the congress, the whole country was covered with beautiful, colourful posters with a swastika, a farmer in a top hat, a hoe on his shoulder and a bunch of large, white grapes. Another poster depicted two bunches of grapes and, of course, the swastika. They were designed by Max Eschle, a Nazi artist still famous for his graphic design of the 1936 German Olympics and his designs for postage stamps associated with the event.

Beneath a huge portrait of Adolf Hitler, many MPs praised the Führer for wonderfully putting internal affairs in order (this was after the Anschluss of Austria and the occupation of Czechoslovakia!). And the President of the World Wine Organisation, the French Socialist MP Édouard Barthe, still managed to implore the German leaders to persevere in their efforts despite the enemies lurking everywhere, and thanked “his excellency, Chancellor Hitler, for having devoted his intelligence to the service of his country”. On a side note, Barthe voted a year later for the fall of the French Third Republic, in favour of the rule of WWI hero Marshal Pétain and the Vichy government, which did not prevent him from becoming a noble French senator after the war.

However, on the third day of the congress something suddenly went wrong – the evening entertainment programme was cancelled, and the next morning the participants were kicked out of their hotels, the phones in the city were cut off, they were packed into buses and escorted by the military to Saarbrücken to the French border, where customs officers unceremoniously combed through their luggage. The reason was simple: the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact had been signed on 23 August, and the date of the invasion of Poland was approaching. Hitler was euphoric and did not want any foreigners in his country.

Mulled wine for defenders and weinführers

When Germany invaded Poland and France declared war on them, the trouble began. Paris fell before the French realised that such a situation could happen at all. Before that, the French had manned the borders and organised a gigantic logistical operation to send wine to the soldiers at the front. Wine was brought to huge warehouses, where large batches of supplies from different regions were mixed together, and sent to the border, on the 700-kilometre-long Maginot Line. The French were afraid of sabotage, such as the poisoning of wine by German agents, hence such blending points were heavily guarded. When the autumn of 1939 and then winter came, mulled wine, or rather the ingredients for making it, were sent to the soldiers. “Le vin chaud du soldat"”(mulled wine for the soldier), exhorted the posters on the walls. They hung alongside posters with slogans: “We will win because we are stronger”.

The latter are one of the most interesting propaganda objects of all time – they depict a map of the world and France with all its colonies in Indochina and Africa, plus Britain, and at the top a small black spot in the shape of Germany. It was soon to be revealed that this spot would be much larger.

The purchase of wines by the Germans during the war was planned even before the aggression – specific people were appointed to manage individual regions, whom the French called weinführers. They were well acquainted with the local market, having traded there for years, and almost all of them spoke fluent French. They knew this country better than many Frenchmen. And it should be added at the outset that they were not idiots – they knew their way around wine, its production and its specific features, and were the last ones to get finessed. Besides, they had any number (tens of thousands) of French helpers-collaborators in the industry at their disposal. Masses of wine-swindlers roamed the country, eager to make a pile by trading with the occupying powers.

The winemaker has to nurture the vine almost all year round, and then still make wine. So if the Germans wanted a steady and decent supply of wine for years to come, why would they want to kill the golden goose vineyards? The Germans paid well for the beverage and, in addition, offered almost constant pick-ups. When the Vichy government taxed vintners for trading with Germany, the vintners raised the purchase price by the same amount. Of course, there were Weinführers who had sticky fingers and set aside a large portion of the purchases for themselves.

The best wines went to fascist notables, according to the hierarchy of uniforms. Cheaper ones – in tanks or barrels – were bottled in conquered countries, for example in Krakow or Warsaw. Although, even in Poland, there were wines such as the highly prized Bordeaux Medocas with German labels.

It is likely that these “sticky fingers” and suspicions of improper apportionment were the cause of conflicts between the Weinführers and various Nazi services. The fastest to react was the Abwehr, which had quite a lot of freedom of action in the occupied territories. It simply began contracting the wines by itself and sending them out to its commanders. Soon the Gestapo and SS and other military services followed suit.

In the polish TV series “Stakes Larger Than Life” Hans Kloss from the Abwehr always has a good cognac in his bar, and on holidays or New Year’s Eve – champagne. Famous wines and cognacs appear in Krakow restaurants in the song “Schindler’s List”; the protagonist himself asks in a pub for a Burgundy Romanée-Conti – today the most expensive wine in the world, a bottle of which is hardly seen even at a window display – as if he was sure that he would naturally receive a positive answer.

The great plunder

Huge quantities of fine wines were seized in France at the beginning of the war, but it was not a question of loss of profit for the winemakers, rather the restaurateurs, who quickly “were disappeared”. The Germans in large and small towns occupied the best venues, famous hotels with restaurants for various services, and the restaurants themselves, for their parties. What they found in the cellars, they treated as their loot. And in such places, the rule was and is that the sommelier (a wine specialist) annually buys spiffing spirits from well-known and trusted suppliers. These wines are often not ready yet, they mature in restaurant cellars, almost never reach the shops and are a magnet for customers with a long purse – others do not frequent such establishments. And this is certainly what the French have tried to hide or wall up and protect as much as possible.

But often it just was not possible. In the famous five-star Hotel Lutetia in Paris, 75.000 carefully catalogued bottles of wine fell into the hands of the Abwehr! Often it was this precise cataloguing that contributed to the great losses. The Carlton hotel was taken by the Kriegsmarine, the George V (considered one of the best hotels in the world and depicted in more detail in “French Kiss”) by the Wehrmacht, the Ritz by the Military Transport Command, the Astoria by the Armaments Inspectorate and so on. They all stole as much as they could, because the cellars were full and well-labelled; they sent gifts to their superiors and families. Intoxicated by the quick victory, the Nazi soldiers barged in to open and closed pubs to celebrate the victory, stealing right and left.

However, this was actually a fraction, probably a tiny fraction, of the wine trade during the war. Hundreds of millions of bottles and rail tankers streamed into Germany. No doubt artificial walls were put up by the owners of the best wineries, in Bordeaux, Burgundy or Champagne – such places have so-called “archives”, i.e. cellars where some bottles from the best vintages are stored.

Christophe Lucand’s book is an interesting look at the wartime affairs in the Seine Land, written with integrity by a French historian. The winemaker, like any farmer, works with whatever he has in his field or barn. On the other hand, it is difficult to equate winemakers with people who risked their lives fighting the occupying forces. This war was by no means “La Grande Vadrouille”. It is also impossible to ignore the fact that after the war France became a great export power... Lucand’s reading is worth recommending and reflecting on.

– Wojciech Gogoliński

–translated by Jan Ziętara