When I fell victim to such a mistake a few days ago, I realized how deep my fears were that some kind of dream about Russia in the minds of Western elites might materialize suddenly and unexpec-tedly, like a black swan that would come unnoticed and change everything.

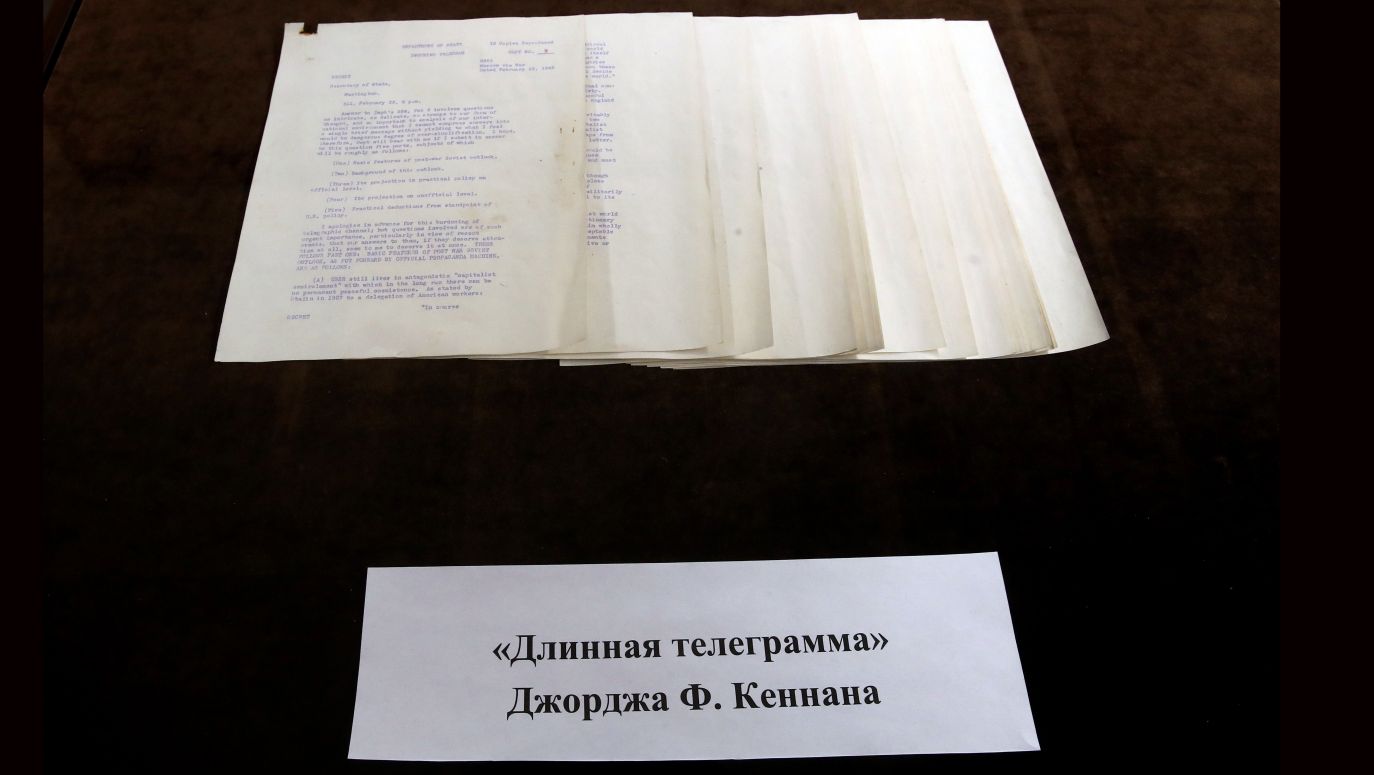

I came across a text whose title intriguingly combined the charac-ters of George Kennan and Vladimir Putin. The latter needs no in-troduction, and the former is a legendary figure for generations of American diplomats and political scientists. Kennan was renowned as a Sovietologist and diplomat in Moscow during Stalinist times. He was the author of the famous "long cable" from Moscow written in 1946, which was the basis for the policy of containing commu-nism that became known as the Truman Doctrine.

Given Kennan's long life, deliberations such as "Did Kennan pre-dict Putin?" have intrigued me. After all, Kennan died when Vla-dimir Vladimirovich had been in power for five years. Like Kissin-ger, Kennan remained intellectually fit even as a 100-year-old. His comments, therefore, could well be based on an analysis of the dictator's actual behavior.

Подписывайтесь на наш фейсбук

Подписывайтесь на наш фейсбук

I found it even more intriguing that this article, published in the il-lustrious American magazine "Foreign Affairs", which is read by everyone interested in international politics, was unsigned -- so-mething unheard of. How significant is this? It depends on what its intended message was. The thesis of the article revolved around Kennan's strong opposition to NATO's expansion in the 1990s, as well as his belief in the "greatness of the Russian nation", that he maintained must finally free itself from dictatorship, because "tota-litarianism is not a natural phenomenon".

These latter formulations were contained in an unsigned article pu-blished in "Foreign Affairs" in 1947. Initially, the text was anony-mous because Kennan was then in the diplomatic service. Knowing this aroused my concern that what I now had before me was more than just an essay by one author, and that the views offered might be endorsed by a larger group of people influential in the American elite. The cliche about the "greatness of the nation" had been used many times to justify concessions to Russia.

A quote (from 1951) cited in the text, referred to the dream of a Russian government that "unlike the one we know now would be communicative, honest and tolerant". The article ended with the reflection that the Russians "one day would begin the process of getting rid of totalitarianism", just as they had done in the early 1990s. "Not everyone in the West shares Kennan's view that totali-tarianism in Russia is also 'our own tragedy.' He may have been wrong on many points, but he was almost certainly right on this one," the author concluded.

At this point I returned to the debates about NATO expansion in the days when Russia had been trying to shed the legacy of com-munism. At the time, the aged Kennan had argued that doing so would be a mistake that would fuel Russia's "nationalistic, anti-Western and militaristic tendencies"; [that it] would have a ne-gative impact on the development of Russian democracy and would steer Russian policy in a direction unfavorable to us."

It is a model thesis for American realists. Its logical extension is the belief that the invasion of Ukraine was caused by the expansio-nist policy of the West and the belief in Russia that the existential threat it faces stems from this belief. This thesis currently serves to justify the quick need to conclude the peace on terms satisfactory to Russia and to recognize Moscow's sphere of influence as one that NATO should not interfere with. This view is often encounte-red in American journalism, but always in a peripheral role -- never as a dominant discourse or a kind of "manifesto". Despite this, an unsigned text in "Foreign Affairs" carries weight and importance.

Подписывайтесь на наш фейсбук

Подписывайтесь на наш фейсбук