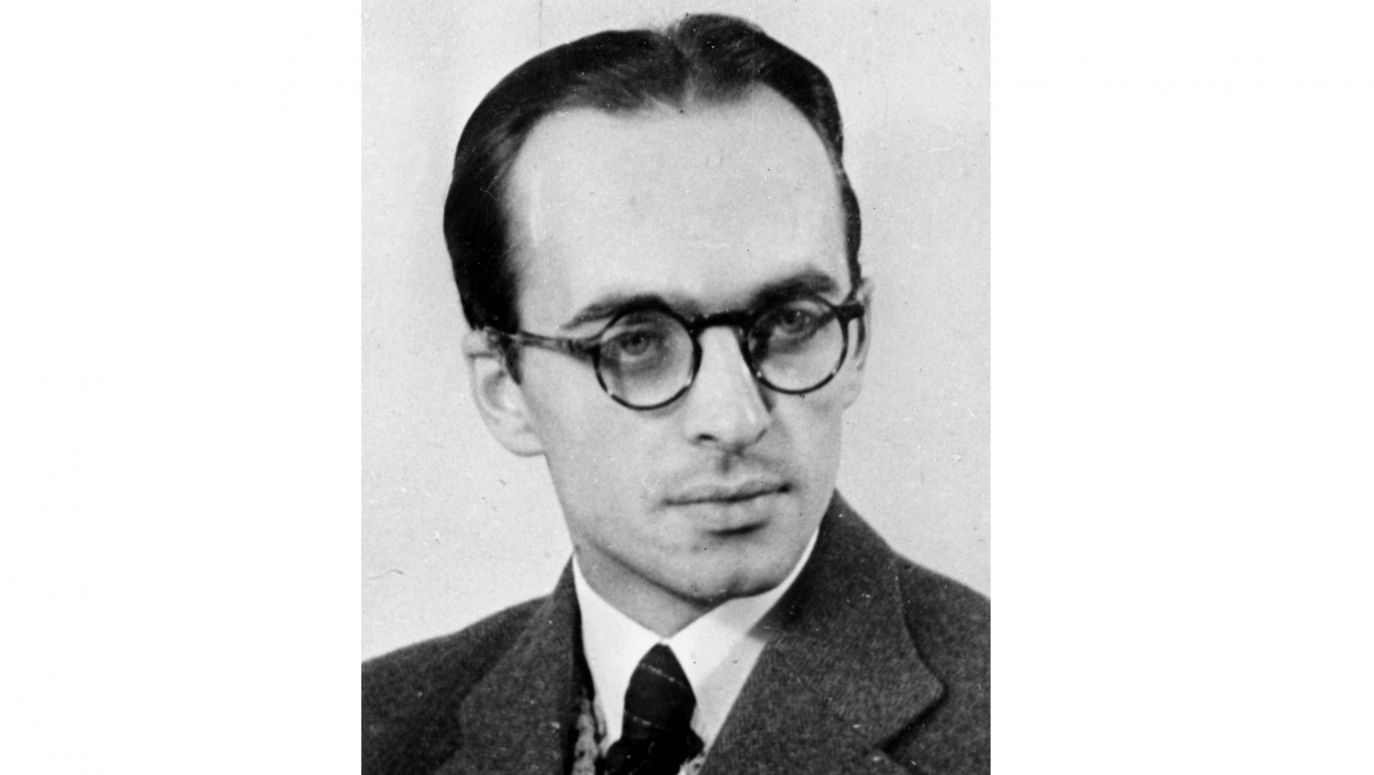

Juliusz Mieroszewski criticised this position. He was convinced that it was anachronistic, and condemned Poles to constant feuds with Ukrainians, Lithuanians and Belarusians, i.e. nations deserving their own states after the collapse of the Soviet empire. However, he saw in the policy of the “Castle option” the persistent aspiration to reverse the course of history in order to regain the eastern lands of the Second Republic, and the instrumental treatment of the nations inhabiting them – solely as cannon fodder against the Soviets.

In turn, when arguing with the faction represented by the émigré National Party (Stronnictwo Narodowe) and its press organ – the London-based weekly Myśl Polska – Mieroszewski reproached it for its pessimistic and fatalistic view of Russia.

According to the columnist, after World War II, the National Democrats residing in the West approached the USSR in the same way as Roman Dmowski [Polish politician, statesman, co-founder and chief ideologue of the National Democracy political movement, and Minister of Foreign Affairs between October and December 1923 - ed.] had approached the Tsar at the beginning of the 20th century. Mieroszewski cited an open letter to Nikita Khrushchev that the Parisian monthly Horyzonty published in 1959 as an illustration of this attitude. This correspondence declared the will of a future non-communist Poland to cooperate with the Soviet Union across political and ideological divides.

According to Mieroszewski, the people who wrote this memorandum (and it is still assumed that it was written by National Democracy politician Jędrzej Giertych, who settled in Great Britain) were convinced that there could be no other Russia than an authoritarian and imperial one, and that the political system prevailing in it played no role.

Hence, the author argued, the conclusion for them was that it was unproductive to seek opposition forces sympathetic to Polish independence aspirations within the Soviet Union. That is why this milieu was in favour of making deals with the Russian establishment – regardless of whether it was white or red.

In Mieroszewski's eyes, this position – as was the case with the 'Castle' option – reeked of anachronism. The publicist recalled that Dmowski was in favour of keeping pace with the main currents of the era, and in the second half of the 20th century, nationalism was one of them. The only thing was that, for Mieroszewsk,i what mattered was the multiplicity of nationalist elements. He saw strong forces in the Ukrainian, Lithuanian, and Belarusian nationalisms that could split the Soviets from within.

And here, we come to the most intriguing strand of the “Polish "Ostpolitik"'. Mieroszewski was not a supporter of the National Democracy, and yet, in a sense, he decided to save Dmowski's thoughts from what his "late grandchildren" wanted to do with them. And they wanted to continue doing so, but no longer in exile, but in Poland. It is about various groups outside the mainstream of Polish politics who, instead of creatively developing the legacy of National Democracy, reconstruct it. And they do so in order to give vent to their own idiosyncrasies, among which the idealisation of Russia and demonisation of the West are conspicuous.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

Meanwhile, a paragraph in Mieroszewski's text is particularly relevant: “All in all, the wisest [National Democracy supporter] will not convince me that Dmowski, were he still alive today, would have written letters to Khrushchev or Brezhnev, nor will anyone convince me that Dmowski … would have disregarded the liberation movements of the Ukrainians, Lithuanians or Belarusians and expressed his readiness to make a deal with official Moscow at the expense of these nations. For Dmowski would have realised that the Ukrainian problem is something completely different today than it was 50 years ago, and requires a reorientation of Polish policy in this respect.”

This opinion of Mieroszewski is most justified. In terms of tactics, Dmowski was a flexible politician. And his pact with the Tsar was precisely tactical. For he had a hostile attitude towards Russia. He saw it as a barbaric, partitioning country.

At the same time, Mieroszewski – willingly or unwillingly – agreed with Dmowski on a key issue: by defending Poland's "Yalta" borders, he supported the model of a Polish nation-state as opposed to the mirages of multiculturalism following the reign of Grand Duke of Lithuania Władysław II Jagiełło.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE