Kazakh belongs to the Turkic group of languages (Kipchak-Nogai subgroup). These languages are spoken by many millions of people, from North Macedonia and the Crimea, through Turkey and Azerbaijan, to Russian Siberia and western China. Kazakh is quite distant from Turkish; as a result, a Kazakh may have more problems communicating with a Turk than, for example, a Pole with a Serb.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

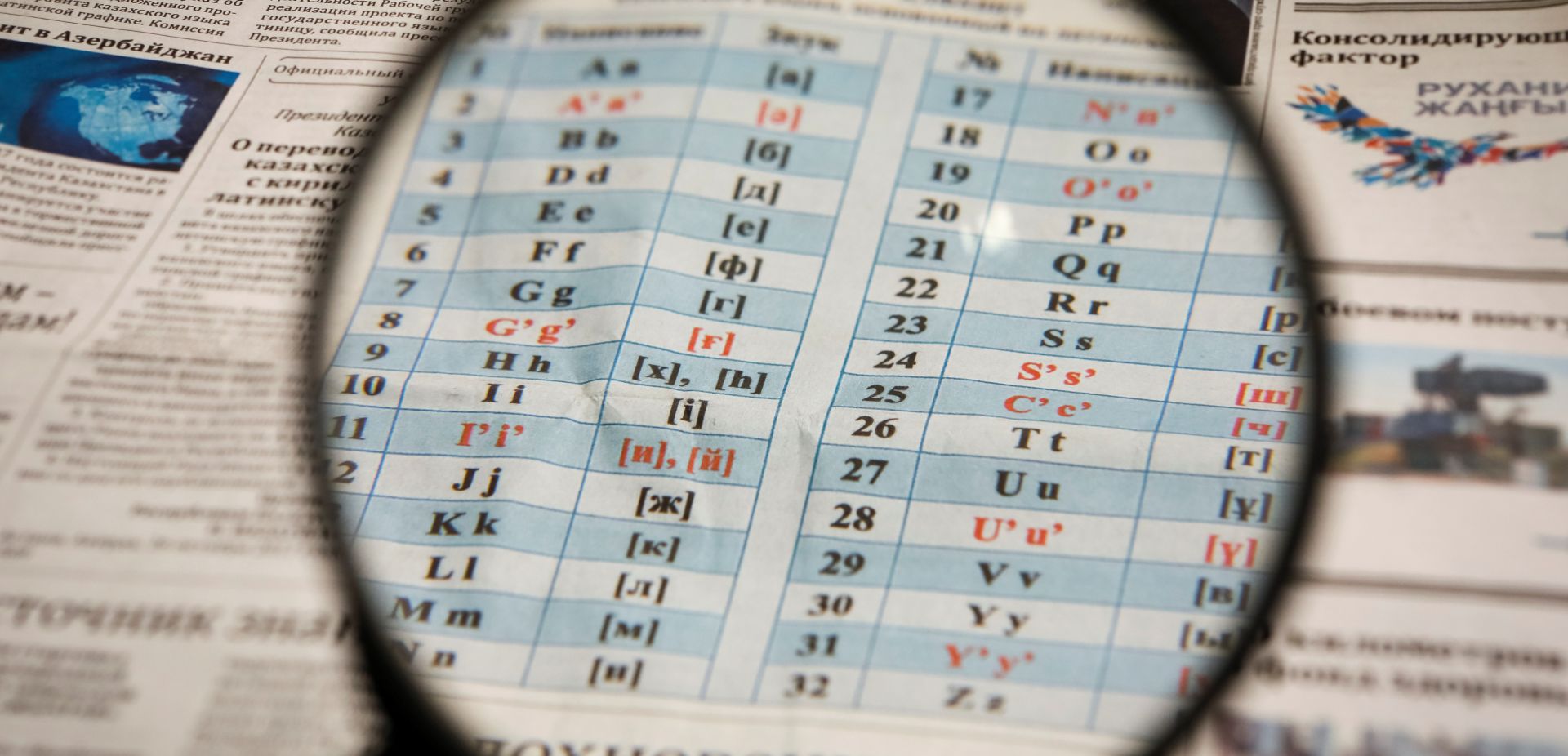

Kazakh is based on the dialect of Alma-Ata, the former capital of Kazakhstan. Originally written in Arabic, the Latin alphabet was introduced in 1929, but a switch to Cyrillic was ordered as early as 1940. In independent Kazakhstan, a switch to Latin was considered several times. In 2006, this was discussed by president Nursultan Nazarbayev; at the time, it was estimated that the cost would be $300 million and the process would take up to 12 years.

In 2007, Nazarbayev abandoned the idea and returned to it ten years later. Presidential Decree No. 569 of 26 October 2017 mandated the replacement of the Cyrillic alphabet with the Latin alphabet by 2025. The details were not disclosed until the end of January 2021, when the Kazakh government announced that the entire operation would take place between 2023 and 2031.

Kazakhstan has a large Russian community – around 25 per cent of the country’s 18.75 million population – and Russian is spoken by more than 90 per cent of its citizens. There are estimates that only 66 per cent of the population speaks fluent Kazakh. But “kazakhisation” has been going on for years. There is a rule that offices, institutions and even companies should be headed by a Kazakh, while representatives of other nationalities, including Russians, can only be deputies.

The authorities are pushing for increasingly widespread use of Kazakh, setting deadlines by which every citizen should already be able to speak it. They want Russian to be recognised as a foreign language – just like English. And teach three languages in schools: Kazakh, English and Russian.

“In Kazakh schools, in the primary grades, it is necessary to teach exclusively in the Kazakh language. And only then can English be introduced. But Russian is not necessary. It should be completely removed from the curriculum. I am an Orałman [compatriot – Kazakh] from China. I returned to my historical homeland 24 years ago. I don’t know a single word of Russian and I haven’t tried to learn it. And I don’t suffer because of it” – wrote well-known poet and social activist Auyt Mukibek to the Minister of Education last year.

Russian media were outraged that Kazakhs wanted to persecute Russians. The authorities have denied that they want to restrict the use of Russian, but the political situation in the world favours the Kazakhs. Russia, involved in the war with Ukraine, is weakening, and Kazakhstan has a very strong ally backing it up – China. Hence the acceleration in the transition to Latin.

Initiated by Azerbaijan

The transition to the Latin alphabet was started by Azerbaijan. In this country the situation was somewhat similar to Kazakhstan: Arabic was used first, Latin was introduced in 1922, replaced by Cyrillic in 1938. But in 1992 the transition to the Latin alphabet began again and lasted until 2003. Azerbaijani is very similar to Turkish, although it has its own additional letters in the alphabet.

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE

SIGN UP TO OUR PAGE